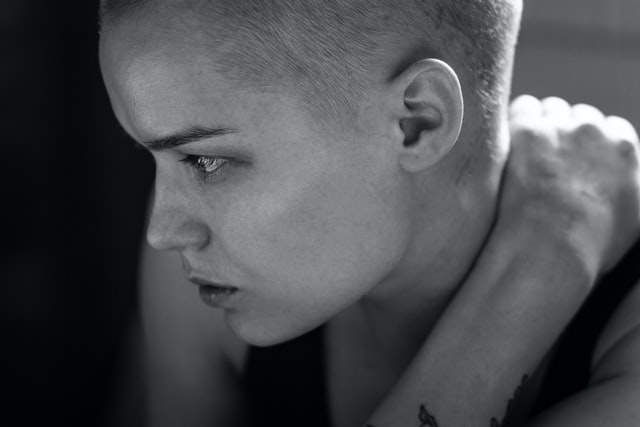

I was preparing to teach yoga to patients in a psych unit.

I’ve Got Your Back.

It was July of 2018 that I first set foot in the psychiatric unit of my local hospital. I was a month out from beginning yoga therapy training at Kripalu Center for Yoga and Health. I had been teaching yoga for nine years and had attended training after training with brilliant teachers.

Now I was taking on something unfamiliar. I was preparing to teach yoga to patients in a psych unit.

I’d teach a group chair yoga class for 30 minutes, that I knew. Following the group class I’d work 1:1 with patients who had been unavailable during the group class (as in, meeting with their doctor/social worker), too sick (physically/mentally/both) or were kept away from the general population for safety.

~

“My vagina’s holy grail, seriously.” Bid farewell to a weak pelvic floor with this award-winning, ingenious device + a free bag of craft Arabica coffee >>

~

First, it was time for me to see what life was like for patients and staff on the unit. I shadowed staff for several hours over the next couple of weeks, basically to see what I was getting myself into—if I could hang. There were also details to work out and procedures to learn: what room would I teach in, and would I be able to manage a class of patients turned yoga students, many who were brand new to yoga?

It was lunch and most patients were just finishing up their meal. I watched as the nurse collected and counted knives (weapons in the wrong circumstance) as one by one people exited the tiny cafeteria.

That first day I learned about the panic watch, a little device with a wrist strap and a button that I was to wear anytime I was in the unit. I was to push the button anytime I feared for someone’s safety. Also, that day, I learned how quickly backup would arrive when called.

While I didn’t see it happen (I was around the corner), law enforcement was called when a patient punched the wall. I don’t remember the reason, maybe I wasn’t even aware at the time. An argument? Tired of being away from home? I can’t say. It wasn’t unusual to see maintenance replastering, painting, and covering up walls, or desks that had been defaced.

There were cameras in the public rooms and near-constant bed checks—everyone was accounted for. There was a locked door to enter and exit the unit and a second door locked in the evening. Once inside there were more locked doors, an office, storage/staff room, a community/craft/therapy room, and now a yoga room all in one. That room housed computers, scissors, pencils, and other sharp, potentially dangerous items needing to be restricted. Another locked door in the back, and on the other side patients were watched even more closely. These patients were monitored not just by cameras and bed checks, but a live person 24 hours a day.

It was decided I’d teach the group class in the community room, once a week to start, later twice a week after receiving positive feedback. There would be enough chairs for a decent size class,15 maybe, which I’d set up in a circle. I purchased two cheap yoga mats and plenty of individual boxes of raisins to use for a mindful eating meditation and was reimbursed by the hospital any time I needed to replenish my stock.

The mats were used working 1:1 with people who either needed more individual attention or wanted a more physical yoga practice than I could give them in the chair class. Yoga straps would not be allowed (for the same reason shoelaces, cables, and the like were not allowed in general).

In theory, I was all set, but what would it be like? Most of my students would be new to yoga, from all walks of life, various ages, abilities, and diagnoses. What would it be like teaching yoga to such a wide and also unfamiliar demographic? Attendance was encouraged but not mandatory.

Would anyone even want to come to my class? Would I be able to get my message across to people who were in so much pain? Had I learned enough, lived enough to help? How far would my calm demeanor, quick smile, and patience be tested?

From my first group class, I learned the biggest struggle would be managing the talkers. Was this payback sent from my high school teachers? When I was the one distracted, preoccupied. How would I allow the big personalities to shine without overlooking the subdued and still get my message across?

Practice. Patience. Persistence. And plenty of creativity. The goal being, for everyone (including me) to be seen, equally a part of the group.

I became adept at rerouting situations and diverting topics. I used yoga breathing techniques and simple stretches like a spell to calm, invigorate, and focus the group. If I could let my students be themselves, while giving my support through a smile, a question, and acknowledgment, my yoga training and technique did the work all by themselves.

Sometimes, classes were full and boisterous. Others, sullen and sparse. Regularly, I knew I had made a difference; sometimes, I didn’t. It was demanding teaching those classes. The first few months, it wasn’t uncommon to feel a headache coming on on my drive home.

But my students told me they felt “lighter,” “more awake,” “regenerated,” “sleepy,” “a calm they never experienced before in their life,” and that I helped them get through a day’s worth of cigarette cravings.

I was told by recovering addicts that they felt high—a natural high—from the breathing exercises we did. I was told they were able to fall back asleep every time they used the breathing technique I taught them last week.

Some of my students were on the unit just a day or two, others for weeks, even months. Many returned fairly regularly after a respite back at home. Slowly but surely, I learned to manage my stress level, taking time before and after teaching on the unit to relax, meditate, rest.

My regulars often requested Bee Breath (a technique where you make a buzzing sound on the out-breath which lengthens exhalation), specific back relieving techniques, and anything to get tension out of their shoulders and focus their wheeling mind. I learned quickly what gave them the most bang for their buck.

What I didn’t expect was how relatable my students would be.

While many were facing extraordinary challenges and fighting excruciating battles, they were familiar. Really, they were like everyone else I’ve ever known—they wanted to feel well, to be free of pain, to be with their loved ones (pets included!), to be loved, cared for, and appreciated.

They were soccer moms (and dads), grandparents, athletes, bosses. Someone’s child. They were wealthy, homeless, business owners, recently out of a job and they shared their stories with me.

Sometimes they were from amazing circumstances that were almost unimaginable to me. They were all people I wanted to spend time with, that I wanted to get to know. People you see on the street and imagine what their life is like and how it’s different from yours, how it’s the same.

They came to my yoga class for the same reason anyone comes to my class, the same reason I do yoga. To feel better.

My goal in every class I teach is to have my students’ backs. To set aside my agenda and meet them where they are. To lift them up when they needed a boost and ground them when they were floating away.

I never did use that panic button. Not once did I feel unsafe. Of course, this is only my story. I’m sure there are many stories to be told that are similar and with just as many strikingly different.

Unfortunately, as with many similar programs, I’ve been unable to continue this work. I’ve been unable to teach in the unit (or outpatients and support groups) since the COVID-19 pandemic swept the nation in March 2020. I am a full-time yoga teacher; I make my living charging for my services. Although I’m not on the unit, I’ve been fortunate enough to be able to continue making a living teaching group and private sessions online.

The problem is—I’m struggling to reach those who are most vulnerable.

Not only do I need some students to share my overwhelming supply of raisins with, but I also want to connect with the people who most need a helping hand, a leg up, someone to have their back. People who can’t afford to pay for a class, who do not have access or transportation to attend in person, or the tech-savviness or internet access to attend online. Those who need the support of their doctor, nurse, social worker, the insurance company, community, neighbor, or contemporary to take advantage of a helping hand.

I hope to find new and different ways to have their back. To model asking for, giving, and receiving support. To give back to the community who have shown me they are the same as me, and you. There is no separation.

Mental illness is like other reasons you go to the hospital, to find support.

I don’t see people judge patients with cancer or who need an organ transplant. We lift them up, raise funds, wear pink, and remember those we’ve lost. We have their back.

Mental illness has been called a “silent killer,” and the truth is, people in our communities are struggling. You may be struggling. Someone you love may be struggling.

With support groups, libraries, senior centers, churches, and alternative therapeutics harder to come by and contact in general so limited, how will we have each others’ backs?

With a smile? A hello? A compliment or thank you…a card…a phone call. Shoveling a walkway or paying-it-forward. There are so many ways; I know you’ll think of more than I.

Times are tough for so many of us; having someone’s back might change that trajectory.

You see, it works both ways. Being supported feels amazing, but giving support does too. It may take practice, patience, and persistence but how can you have someone’s back today? Tomorrow? The next?

#Igotyourback

~

Read 34 comments and reply