There are two commonly known formulas for uncovering the validity of an argument, and these are Deductive and Inductive Reasoning. These formulas are often explained with the following arguments:

-

All humans are mortal

-

Socrates was a human

Conclusion-

Socrates was mortal

This is a neat and tidy deductive argument. It asserts that is the first two premises are true, then the conclusion is valid. Validity means that philosophically speaking, your argument is true. An important thing to note, however: valid does not equal true in the real world sense.

We will explore this more in a moment.

An example of an Inductive Argument is the following:

-

Most men in America wear jeans

-

Patrick is a man in America

Conclusion-

Patrick most likely wears jeans.

Inductive reasoning deals with probability rather than the establishment of a “true” argument like deduction. For many this formula seems more useful, since we all know the world is primarily a collection of probabilities over absolutes.

Both are concerned with one thing, though: TRUTH.

These systems seem so easy and simple, have we found the best methods for finding the truth?

Of course these systems have proven invaluable in the academic field of philosophy, but how do they apply in our daily lives? We will explore these systems further with the exploration of a little historical anecdote.

Socrates

Socrates was a man in Athens, who lived around 470 BCE. Through our Deductive reasoning we have concluded he was a mortal. At the time he lived most men in Athens grew out their beards. With our inductive reasoning we might conclude that Socrates most likely grew out his beard as well.

Right?

Well, it turns out the truth is more difficult than this.

Apparently, it isn’t so simple to determine whether Socrates had a beard or not. A contemporary of Socrates accused the philosopher in an early draft of the dialogue entitled “Gorgias” of being incapable of growing a beard.

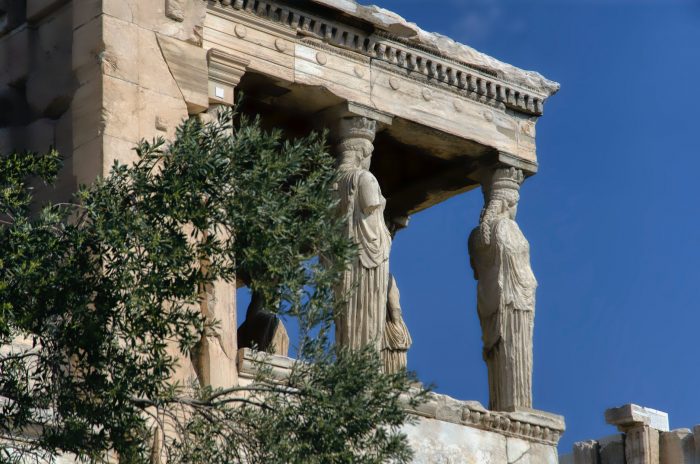

This might sound ridiculous to many of you who have seen carvings of the bust of Socrates and have seen that the man does indeed have a rather vast beard. But, someone may counter, this could have been added by the craftsman. Maybe he wanted to honor the philosopher by giving him a beard even though he could not grow one.

This is unlikely, you respond, since its just ridiculous to doubt the craftsmen who would probably be rebuked for such a lie.

Your contender then asserts that in the Gorgias the contemporary asserts that Socrates used to steal clippings from a barber shops to make a false beard. So there is historical contexts which encourages us to doubt the craftsmen.

Although with further research, you find that this contemporary did not like Socrates and was trying to defame the thinker. This raises two very interesting questions regarding the truth.

Who can be right in the above argument? We have one person who believes they have good reason from historical documents to doubt Socrates’ beard as real.

Although, you can’t help but wonder about this claim. Is it really reasonable to believe this contemporary? You feel stumped.

When evaluating historical records it’s important to take WHO is talking into account. With the case of Gorgias, you have cause to doubt him as a source of information because he apparently disliked Socrates.

This is known as Historical Bias, which entails the corruption of historical records or personal testimony due to a bias to find a certain conclusion. This applies to things other than Socrates’ beard.

What about people who doubt the Moon landing? What do they doubt, at the core? They doubt the witnesses to the event. So, the question is, what can we trust about the past, and why?

This may sound absurd, but when Socrates’ contemporary challenged his ability to grow a beard he was challenging his reliability. In a sense we can see this challenge as an ancient Athenian attempt to challenge his manhood.

This sounds ridiculous to us today, where a man’s ability to grow a beard is pretty much irrelevant. Although, it really isn’t very foreign at all.

Think about a political smear campaign ad. How much of that ad really had anything to do with effective policy making? What challenges actually pertained to the candidates voting history as a way to show his ability to lead? Instead we are left with news stories about ice cream, McDonalds and where they shop.

In other words, we often times make decisions based upon our gut reactions to social norms without actually examining evidence.

In ancient Athens a man not being able to grow a beard might cause some to doubt his ability to “be a man” and be trusted. Today, we look at someone’s beauty, or handsomeness, or their diet and draw irrelevant conclusions about their ability to reason.

How does this relate to Deduction and Induction? When we attend Philosophy 101 in college and we are presented with these obscure, math-like, irrelevant formulas and shrug them off.

Okay, I know how to make a philosophical proof to pass my test. But, what are you really learning here?

Each of these proofs are fundamental for the establishment of philosophical intercourse. These proofs ask us, what do you know? How do you know them? And, most importantly, What do you do with what you know?

This post isn’t designed to answer anything for you. It is meant to make you curious and to check you presumptions.

Did Socrates have a beard? Does his beard cause you to question his capacity to reason? This is the most important take away.

Some helpful links:

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply