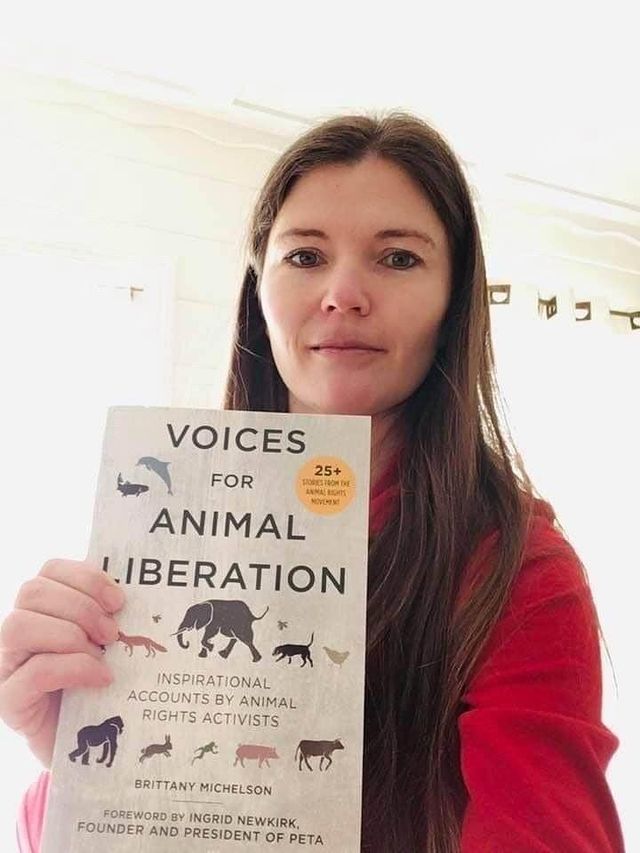

The following is an excerpt from Brittany Michelson’s book Voices for Animal Liberation: Inspirational Accounts by Animal Rights Activists.

~

Like many children, I grew up loving animals.

My family had a variety of pets that we adored—dogs that slept on our beds, rats that my brother and I made climbing structures for, guinea pigs we let scurry around our bedrooms, and other furry and shelled companions.

While we considered ourselves animal lovers, we would sit down at the dining room table to eat spaghetti with meat sauce, lemon chicken, and tuna melts. And there was always ice cream for dessert. We didn’t think of the animals we were eating. We also thought nothing of the leather shoes and wool sweaters we wore and the down jackets for skiing.

When I was a high school senior, my brother who is two years my junior and had recently stopped eating meat, showed me an undercover video that was my first glimpse into the animal agriculture industry. It was a PETA video from a meat-producing facility. I remember the cow that hung upside down in a warehouse-like building. I remember her face and big eyes, her degradation and defenselessness, and the angry man kicking her with a large boot.

I was stunned, the air nearly sucked out of me. It was as if my cells had rearranged with this new knowledge of where meat came from. I loved animals; didn’t most people? How could this be allowed? Why was nobody stopping it? The wide eyes of the gentle animal stared through the screen with a mix of fear and surrender, and I could do nothing but stare back at her suffering. There was innocence, hanging like an object.

I made it through only a minute of the video, then reached over and shut it off. I locked eyes with my brother. There was a thick sadness between us.

I could never unlearn what I had learned.

I wish I could say that the video made me instantly give up meat, but 17 years of ingrained meat-eating was more influential than the sadness I felt over that suffering cow. I tried to justify meat consumption by telling myself that humans had always eaten it, that we are omnivores, that we need meat for protein. All of my friends ate meat and my father owned a restaurant at the time that was known for its steaks. I also told myself that the footage my brother showed me was surely an exception: that usually cows lived in fields—not in metal buildings—and that they weren’t treated like that.

I shut the video out of my mind and went on with my busy teenage life, but the visual of the hanging cow in the building surfaced, creating an unsettled feeling inside of me. I found myself questioning the reality behind meat, but I didn’t allow myself to do any research because I never wanted to be subjected to images like that again. The pressures of maintaining a successful grade point average, managing a demanding Varsity sports schedule, and navigating the dramas of adolescent social life were more pressing than educating myself about what I was eating.

It was easier not to think about it.

Shortly after my brother showed me the video of the cow, I graduated high school, and then a few months into my freshman year of college I decided to become vegetarian. Eating dead animals had started feeling strange to me. I also started buying soy milk because I no longer liked the taste of cow’s milk. I was 18 and living in the university dorms a couple of hours from my family’s home in Northern Arizona.

During my years of vegetarianism, there were periods where I was pescatarian, as I thought I needed the protein and my mom told me that omega-3s from fish were very important. Also, at the time I didn’t think eating fish was the same as eating animals like cows and pigs. It seemed like they didn’t have as much capacity for pain and emotion as mammals do.

My assumption was rooted in speciesism and I had no idea. Speciesism involves the lack of consideration to certain animals based on species classification. Its premise underlies the notion that fish don’t suffer as much as cows, or that animals classified as “pets” are worthy of love and protection while animals who are designated “food” are for human consumption.

What I didn’t know back then is that the dairy and egg industries also operate from serious animal suffering. I thought that cows readily produced milk and were living in fields. I assumed that eggs were collected after hens laid them, and I figured they were pecking atop grass and dirt, certainly not crammed into cages so tightly they couldn’t spread their wings.

I had no idea that animals were genetically manipulated to produce much more than they naturally would. It never crossed my mind that their production levels would go down, nor did I think about what happened to them after their production ceased. I didn’t know that male calves are slaughtered for veal and that female dairy cows are eventually sent to slaughter.

In becoming vegan, I realized that something known as cognitive dissonance had been responsible for the rift between my values and my actions. Cognitive dissonance is the state of having inconsistent thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes, especially as relating to behavioral decisions.

Although I had always considered myself to be someone who loved and respected animals, I had been passively accepting their torture and misery by eating and wearing animal products. I also learned the concept of speciesism, which is rooted in the assumption of human superiority leading to the exploitation of animals.

Becoming vegan was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made.

It was from that moment that I started living in true alignment with my values—as I am against animal abuse, against the destruction of the environment, and against damaging human health. Veganism also resonates with me on a spiritual level—the idea of non-harm to fellow beings—and I realized that, energetically, I didn’t want to consume torture. As someone who values feminism, I realized that I could not accept the exploitation of female bodies, regardless of species.

It is a challenge being vegan in a world that values convenience, tradition, and palate pleasure over sentient lives—but when I feel overwhelmed by the cruelty and frustrated with the societal conditioning that permits animal exploitation, I focus on the amazing community of animal rights activists that I am a part of.

Living in alignment with my values and being committed to work that inspires and fulfills me has also helped alleviate anxiety. My struggles pale in comparison to the nightmare that so many animals are constantly subjected to. Furthermore, while animal cruelty continues to upset me, it doesn’t provoke the level of anxiety that it used to because I know that I am actively part of the solution.

I live for the day when animal exploitation ceases to exist and when nonhumans are valued and respected for the individuals they are. Until that day, I will continue to take action.

~

Check out the book here and here.

Read 3 comments and reply