View this post on Instagram

“Follow the breath” is a helpful refrain often employed by yoga teachers, who aim to stabilize the posture of their students.

It is a well-principled suggestion. Any real yogi will tell you that thought and breath are closely linked, and when one slows, so does the other. Our asanas become unstable when our mind is either distracted (pulled outward) or scattered (radiating outward).

Whenever we bring our awareness to our breath, we subdue both scatteredness and distractedness, and, as we anchor our thoughts, the body follows. The breath will accomplish far more with physical stability than trying to muscle through a posture in a far more subtle and holistic way.

But breath offers benefits that reach far beyond the yoga mat.

It is 1969, and I am in the seaside city of Jagannath Puri, in Orissa, India.

I enter a white marble ashram on a full moon festive occasion and sat with a group of devotees. Their guru is seated sideways to the gathering with a water bowl and flowers floating in it in front of him. He repeatedly picks up a flower, holds it above his head, and as he recites a few lines from a mantra, he drops it on his head. As each flower touches his head, he enters samadhi (breathless state) and emerges a few minutes later.

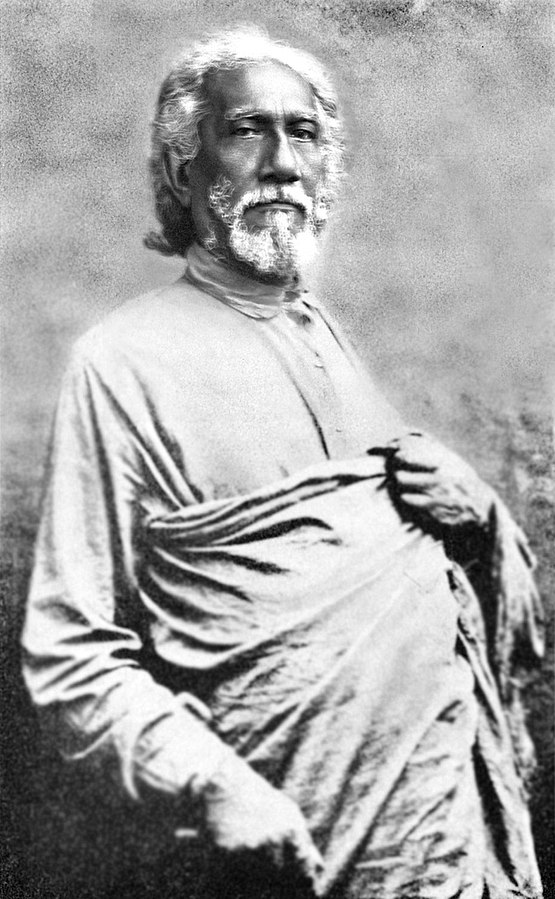

His name is Priyananda Swami, the swami Paramahansa Yogananda installed as abbot to look after the ashram of his teacher, Sri Yukteshvar.

The teaching prior to the demonstration is about the method of kriya yoga that Paramahansa Yogananda becomes so well-known for teaching in America, a method of breath mastery that he personally initiated 100,000 Americans into, and whose ashrams are some of our most beautiful.

The ceremony of dropping the flowers and entering samadhi—at will no less—strangely doesn’t leave me in awe of the master but rather with the feeling of “I can do that!”

I sense that everyone else feels the same way. There is the clear feeling that he is doing the rite for us and not for himself.

Everyone feels blessed.

A sign of his great skill is not only entering the breathless state at will but emerging from it with full intention.

In the lower stages of awareness, one may emerge from it after a few minutes, half an hour, an hour, even a day, or more later, without any sort of control. Being able to maintain awareness through breathlessness is a much higher stage of awareness.

Swami Priyananda clearly reflects what is beyond exalted trance states.

Priyananda, like his teacher, Paramahansa Yogananda, approaches stilling the mad mind through the breath, as opposed to analytical meditation, dialectics, Chan (Zen) mantra, and so forth, whose aim is to still the racing mind.

Either method works, and many use both, usually with emphasis on one: the one we have the most affinities with, the one that feels most comfortable and most natural.

But since it is a big topic—for the sake of brevity—let us talk a bit about breath, and in a practical way that can help us wherever we are in the world, which is becoming increasingly difficult to make sense of.

After all, it may be a drop in the bucket, but our little individual drop of peacefulness, humble though it may be, just might make the world a better place.

When we enter the world, our introduction to breath is usually accompanied by a lot of crying, until we feel the warmth of our mother’s breath on our forehead and her breast in our mouth. From then on, everything goes pretty much on its own until our last exhale.

It has always been a great marvel to me how the rishis of India ever thought to wonder about the breath at all, indeed not only not to take it for granted, but having the intuition to question whether a treasure might be found right beneath their nose. I bow down to those patient sages who had the intelligence, insight, and intuition, not to mention incredible patience, to pioneer the elaborate systems of pranayama (breath mastery) that we have today.

Their discovery is shocking, for it revealed to them not only the outer breath we all are familiar with, but an inner one that dances with it, a breath far more subtle than the one we know so well and that has nothing to do with air. In fact, it is this subtle breath that our coarse breath dissolves into when it fades through the practice of breath mastery.

This is exactly what Priyananda Swami was demonstrating.

One of the beautiful things about breath mastery as a means of stilling the mind is its obvious availability and simplicity. Even advanced forms of breath mastery are far simpler to practice than most meditation approaches.

For one thing, a successful meditation practice involves a deep understanding of the philosophical foundations of the Buddhist or Hindu path (are they really so different?). Breath is always available, a constant companion, requiring no rituals, study, debate, logic, reasoning, deep learning or memorization of mantras or prayers, mind-boggling Chan puzzles, or whacks with the Zen master’s stick.

Breath is right beneath our nose and all we have to do is pay attention to it to learn increasingly subtle lessons from observation as our ability to pay attention increases.

Thought will steady to the degree that the mind is capable of uniting with the breath. We might begin by watching the tip of our nose, noticing it is cool as the air flows in and warm as it flows out, maybe even labeling it as “cool” or “warm” as it flows.

If we try to regulate it—often advised—we may find that we have stuttered breathing, which is not only unhelpful but harmful. So, if the breathing becomes stuttered, just return to observer mode (it can actually take us a long, long way).

For many of us, breath will be a useful tool to help our asanas or bring a bit of peace of mind when stressed, but if we find that much in it, we can easily make it more meaningful.

Above we saw how breath mastery differs from a meditation approach, but both share many similarities. It is tedious, boring, aggravating at times, humiliating, demanding, unflattering, demeaning, and so forth. I might mention here, for all but few, if either meditation or breath work does not evoke the foregoing, or even perhaps the opposite, one is probably engaged in what I think of as “beauty queen meditation.”

Just as a person enraptured with their self-image can stare endlessly in a mirror and never grow weary, some meditators from all spectrums of the discipline can mistake a contrived meditation for the real thing and engage in wrong meditation with great enthusiasm.

If the above is not enough encouragement to give breath mastery a try, consider what Sri Yukteshvar said about it: “One minute of breathless samadhi is equal to one year of natural spiritual evolution.”

So, if you want a high-yield investment in yourself, is it not something to explore?

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 4 comments and reply