I recently landed a new job as an educational assistant and support worker for a family that includes a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

But I have a secret: I too have ADHD.

Wait a minute. You’re an educational assistant and support worker for children with ADHD even though you have it yourself? Isn’t that a bit like the blind leading the blind?

Truth be told, the answer to that question is a multi-faceted one. However, before you jump to conclusions and assume that I must be unqualified to assist another being with this disorder, please keep in mind that I have an educational background rooted in psychology and have interned in various classrooms with young children of all temperaments, needs, and abilities in the past, in addition to possessing an acute perception and deep understanding of other people, in general.

Over the years, I’ve been told I have a knack for connecting with children. I’m able to get on their level and connect with them. I can understand and empathize with their interests, feelings, and experiences. And they gravitate toward me in turn, opening up and bonding quickly.

But yes, it’s true: I have adult ADHD, am unmedicated, and am, in essence, a victor of my own unique challenges with it.

Now, I am seeing my younger self in the eyes of a little girl who is involved in an invisible battle with her own neurochemistry. The difference between us is that I am a lot older than she is and therefore much better able to self-regulate my attention, among many other things.

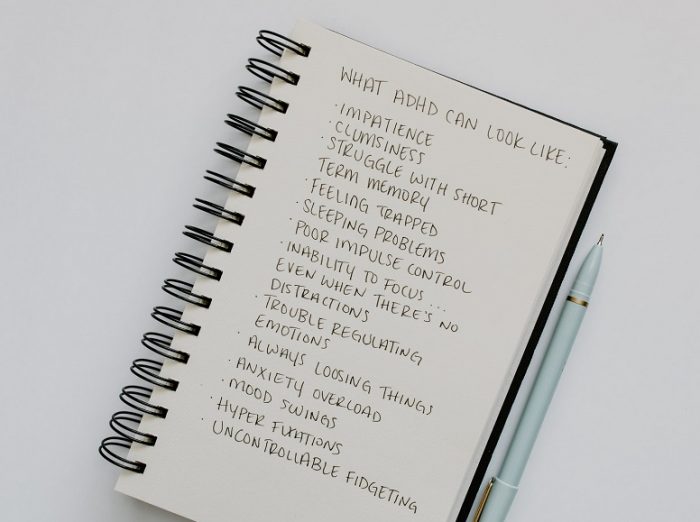

This brings me to a rather important point about the nature of ADHD: it isn’t as much about a deficit in attention as much as it is a challenge in regulating and shifting one’s attention.

At its core, ADHD suggests a problem with the brain’s management system, also known as its executive function. In the brain, the executive function is responsible for several skills including time management, organization, planning, prioritizing, starting and finishing tasks, self-monitoring, regulating emotions, and of course, paying attention. For those of us with ADHD, these skills are fundamentally more challenging—partially due to the fact that we also have a deficiency in the neurochemicals that help our executive function run more smoothly, such as dopamine and norepinephrine.

Dopamine, a neurochemical the ADHD brain is lacking in, is released whenever we are anticipating some kind of reward, either material or intrinsic. Our levels of this chemical also impact motivation, sleep patterns, and concentration. So, when someone is dopamine-deficient, their capacity to experience the rewarding feeling that is a byproduct of accomplishment can falter, causing the individual to almost constantly seek out stimulation in order to experience that “rush” they aren’t getting enough of—especially when the task at hand feels tedious and doesn’t inspire much interest.

During these times of low or waning interest, the brain produces theta and delta waves that on an EEG would look identical to the brain waves of a person who is meditating or on the verge of falling asleep when they’re supposed to be alert (producing beta waves) and focusing on the “boring” task at hand. A person with ADHD will then unconsciously attempt to induce a beta wave state by seeking out “distractions,” which from an outsider’s limited perspective can look like carelessness or even defiance.

On the other hand, many people with ADHD can alternatively hyper-focus when something really catches and sustains their interest for whatever reason. I, for one, can focus on writing for hours on end and barely hear a pin drop. Even after I’ve finished drafting, I can continue to mull over my words and think about a topic in depth while more creative phrases pop into my head. Time can pass without me so much as glimpsing at the clock (unless I have to do something or be somewhere at a certain time) and I can feel so in tune with what I am thinking about or recalling that I actually feel my heart pumping, as though I am re-experiencing the event in question. But paperwork and fine print tasks? Forget it. The best I can do is tolerate them.

Unfortunately, however, when we see a child with ADHD who is sitting at their desk while staring blankly at the wall and tapping their pencil on the wood while a sheet of paper is right in front of them, we are often tempted to label or at least view that child as one who is apathetic or “not too bright,” when in fact, they are exhibiting those surface behaviors directly as a result of a chemical imbalance.

Let me be clear: ADHD is not a character flaw. It is a neurochemical disorder, just as anxiety and depression are neurochemical in nature.

Children with ADHD experience the natural whims typical of most other school-aged children, while simultaneously battling their own neurodivergent brain on a more-or-less constant basis. Like neurotypical children, they would prefer to play rather than sit in a classroom for eight hours per day. The only difference is that for children with ADHD, performing tasks that do not stimulate them is more of a challenge than it is for kids who do not have the disorder.

They are not trying to be “annoying” or “deliberately defiant” when they interrupt others, talk out of turn, or fail to listen; they’re struggling to effectively self-regulate, the way that you and I can. They’re falling asleep and trying to bring themselves into a beta state. They’re unconsciously trying to get a hit of the dopamine their brains are hungering for. It isn’t their fault; it’s the way their brain is wired.

And what I can tell you, from an insider’s perspective, is that many children with ADHD are well aware of their issues and are often just as baffled by them as any adult around them. If you think for one second that the child you’ve thoughtlessly or callously labeled as “lazy” or “ill-mannered” doesn’t already feel like an aberration, you’re quite wrong.

In the years I worked as an intern in classrooms, I heard things out of the mouths of these children that nearly broke my heart:

My dad says I’m no good.

I am a loser.

Nobody likes me.

I’m stupid.

I hate myself.

Why can’t I do anything right?

I wish I could listen but I’m just so bored.

Mom, Dad, and my teachers are always mad at me. I feel like they hate me.

It frustrates me to no end when I see and hear parents and teachers screaming at these children. Whether or not they realize it, these kids are in fact listening and internalizing a lot of the blame and shame being tossed at them. Yes, they no doubt test the patience of the adults in question. But rest assured, these same children are often just as frustrated within the system. Am I suggesting that we should never discipline them or offer corrective feedback? No, of course not. However, I really do believe that our approach to disciplining and offering feedback needs to be held under a microscope.

Phrases such as “you’re being lazy” or “you made another careless mistake” aren’t helpful. In fact, I think we should just omit the word careless. From what I have observed, children with ADHD actually care a lot and have to try a heck of a lot harder than the average person to simply buckle down and persevere in spite of their symptoms. Meanwhile, no one around them is teaching them how to self-regulate. They have to figure out how to do that on their own. Stop and think about that for a minute.

I once read a startling fact: researchers estimate that kids with ADHD hear about 20,000 more critical messages about themselves than neurotypical children—all before the age of 12. I try my hardest to keep this in mind each day I go in to work, knowing that I am supporting this child in an area of her life she finds difficult.

In fact, I make it a point to make note of and praise the child for her many skills and positive characteristics in order to balance out or counteract the negative. I have noted that many children with ADHD have vivid imaginations, a keen sense of perception, and can effortlessly think outside of the box when they need to. This child is no different. During playtime, she gets lost in the ocean that is her imagination and concocts deep plot and storylines for each character. She is also gentle, compassionate, and empathetic toward her younger brother and expresses a concern for the state of the earth. As a result, I am quick to express how wonderful I think it is that she seems so creative and has a vibrant imagination. I praise her for caring about others, owning up to her mistakes, and feeling so strongly against littering.

Furthermore, I am equally careful not to use character assassinations, even when I feel frustrated. Telling a child that they’re being “silly,” “careless,” or “lazy” may not be as effective as we have been conditioned to believe. Instead, phrases that include those words often equate to the child believing that they are those things. A child’s thinking is not as nuanced as an adult’s; they can’t as easily make a distinction between who they are and how they’re acting in a moment.

Breaking a child’s already fragile sense of self isn’t going to produce the desired result; it’s likely going to hurt them in the long run and potentially become a catalyst for self-destruction and self-sabotaging tendencies later on.

Many of the children I’ve met with ADHD have outstanding qualities—they just don’t jive with classroom rules or shine in a school setting, and, unfortunately, these positive traits are therefore often overlooked.

Personally, I’ve witnessed in these kids the following characteristics:

- A colorful imagination

- Ample curiosity about others and the world around them

- Resilience

- A generous nature

- A loving and forgiving heart that knows no bounds

- Flexibility in their thinking

- Open-mindedness

- Empathy for those they perceive as the “underdog”

- Spontaneity

- An outgoing nature

- Outspokenness

- Engaging conversationalists

- A willingness to try new things

- Keen intelligence

- Friendliness

- A good sense of humor

- Enthusiasm toward the things they love and the ability to hyper-focus on them

As a society, we seldom honor and acknowledge these strengths in children. On the contrary, we tend to see them as little pieces of clay that we must mold to fit into a container. Children are not human doings; they’re human beings who deserve to have their experiences taken into account. When I interact with a child, I try to treat them with just as much respect and consideration as I would any adult. After all, I believe that the best way to teach self-regulation and respect for others is to model it.

We need to do more than just tell kids with ADHD to “sit still,” “pay attention,” and “stop fidgeting.” After all, if it were really that easy, wouldn’t they be able to do it more frequently and effectively on their own? Along with other interventions, we also need to teach these children creative techniques to help them self-regulate when they’re struggling to do so. Mindfulness can go a long way, including teaching them to catch themselves tuning out and find ways to help them tune back in when they need to.

Another erroneous presumption is to equate a child’s alternate learning style or attentional dysregulation with their level of intelligence. ADHD has absolutely nothing to do with a person’s intelligence level. You can be a genius and have ADHD. You can be above-average in intelligence and have ADHD. You can also be average or low-average in IQ and have ADHD. There is no direct positive correlation between ADHD and intelligence. Period.

I’ve read about and met highly successful people with ADHD and they’ve often had to persevere in spite of their challenges. Their struggle isn’t any less notable or significant. And no, their ADHD may not in fact be “mild.” As a culture, we’re not always careful or critical with our words and assumptions. Nor do we question our perceptions about other people and their invisible challenges as often as we should.

I desperately wish that we could make room for and even celebrate neurodivergence.

As a child, I could have used someone like the adult I am now. I would have given my right arm to have someone in my life try to understand me—someone who saw through and past the surface-level behaviors. I also would have loved to have someone in my life who built me up as opposed to tearing me down simply because my mind worked a bit differently in the classroom. No, I wasn’t a hyperactive child. I did not exhibit any so-called “problem-behaviors.” However, I had trouble keeping my desk, knapsack, papers, and notebook organized, would lose anything that wasn’t attached to me, and would frequently daydream and miss chunks of information and instructions.

By the time I reached tenth grade, I knew I had ADHD and had learned how to compensate for any challenges or shortcomings—sometimes to the point where many people did not believe me when I told them I had ADHD. I went from being the child who frequently lost her homework to the teenager and young adult who started most assignments early to prevent failure. Sometimes I felt burnt out trying to fit my square self into a round hole, but I pulled through and even managed to make it on the honor roll several times, after I no longer had to worry about passing a math course, which was the bane of my academic existence.

Now, as a working adult, I still sometimes struggle with small oversights and with being lost in thought. I also misplace things in the house, have difficulty shifting my attention from one thing to another quickly enough, and can be rather forgetful—although thankfully, I am almost never late for anything important, such as interviews, appointments, or my job.

Lastly, now that I work with a child with ADHD, I make it a priority to be more mindful of my surroundings as well as to my relationship with the present moment. I try harder to fight against my own tendencies and to catch myself drifting off so that I can bring my focus more fully into the now. I remind myself that having ADHD can feel like having all of your tabs open at once and not being able to effectively ignore internal thoughts and stimuli. As a result, I try to close some of those metaphorical tabs.

Moreover, I understand the importance of learning more about my neurodivergence so that I can better help and understand both myself and others—and possibly spread some awareness in small ways that may have a positive impact.

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 6 comments and reply