Sri Lanka in the mid-90s was not the surfer and ayurvedic paradise it is today.

There were tourists and backpackers and a few upmarket hotels of course, but it wasn’t as sleek as it is today.

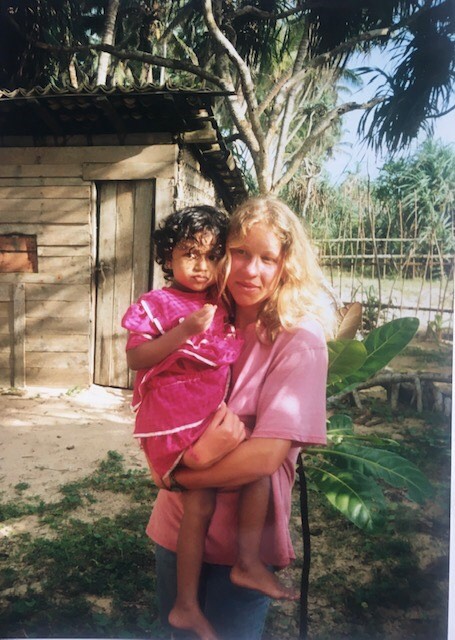

My mother loved this sort of independent traveling, and so at the age of 12, I remember her putting a small rucksack on my shoulders, and off we went to explore the southern part of this beautiful and lush island.

Tropical rain, blistering heat, beaches as long as the eye could see, and cold coconuts cut down from the local palm tree. It was the sort of paradise a child of the 80s and 90s only knew from cheesy Bounty chocolate bar adverts.

We rented a hut directly by the beach from a family who had built four simple wooden shacks, each with a small bed, a hammock, and nothing else. There was no electricity and at night, we lay in bed, blew out the kerosene lamp, and listened to the Indian Ocean underneath our mosquito nets, throwing its 40 waves onto the beach in a repetitive and wild motion.

It was like nothing I had ever experienced.

A well with a make-shift bamboo fence was our “en-suite” as we pulled up the bucket of refreshing cold water and poured it over each other’s heads to wash our hair.

In the mornings, we walked a mile down the broad and sandy beach to the next slightly more touristy place and chose one of the juice bars lining that part of the village. Two young Singhalese men (boys really) sat on the balustrade of one of the shacks, staring out onto the ocean, taking little notice of us.

“This will do fine,” my mother said. We sat down. One of the boys came over with a tired “good morning” and handed us the menus without taking his gaze off the sea or beyond. When our mango lassies arrived, he placed them on the plastic-covered table. “Thank you,” I said looking at him. But he just nodded with a tired smile and no eye contact was made.

When the sweetness of the mango lassie hit my taste buds, I closed my eyes to make sure I would remember this exquisite freshness long after our plane would have touched down on the wintery runways of Europe less than a week from now.

I looked around. Tourists were sitting on plastic chairs having breakfast, or iced teas, or lounging on the slightly frail-looking sun loungers underneath umbrellas made from dried palm leaf.

Although the few tourists there ate and drank and the waiters tended to them, there seemed a veil dividing them both—neither hardly noticing the other.

Perhaps it was just the late morning heat. But perhaps it was also dubiety: we tourists wanting to enjoy the sun and the sea but unsure of much else, and perhaps the locals looking at us and our sunburned skin, wondering what we thought of them.

We were all strangers to one another really.

“I wish we could go swimming.” I turned to my mother. “Let’s!” she said and slurped the last bit of yellow-tinted creaminess out of her glass. “But what will you do with your handbag? You can’t just leave it on the towel.”

My mother got up, walked over to the two boys, and said “I would like to go swimming with my daughter. Could I ask you for a big favor? Would you look after my handbag for me? I can’t afford to lose it.”

The two men looked surprised as if they had noticed my mother for the first time. One of them smiled, “Yes, Miss. No problem, Miss. You go with your daughter.”

I just remember my own astonishment. Out of all the tourists sitting on those wobbly chairs, she chose those two almost suspiciously disconnected guys? Why?

But I did not say anything. As a 12-year-old, you are better at perception than you will ever be when you are older. Too young to make your own decisions, yet old enough to understand what is going on around you makes you a potent observer.

We left our things and walked down to the water. The sea was wild and glorious. The waves were powerful and yet so inviting as we splashed, swam, dove, and eventually tried to swim on one spot while giggling and chatting.

“Are you not worried that they will take the money from your purse? Why did you not give it to the English couple on the sun lounger?” I asked my mother.

“Tina, I did that on purpose. If you put a little trust in people, it can change everything. And putting a little trust in someone is also a gesture of respect: respecting their honesty. I don’t like the suspicion that hangs over this place. Let’s see if I am wrong.”

And so, half an hour later, we bodyboarded back to the shore.

As we tiptoed quickly over the boiling sand back to the café, I could see one of them waving at us. “Was it a good swim?” He asked, his beautiful white teeth breaking into a smile that I could nothing but reciprocate instantly.

“It was wonderful. We love it here so much. Don’t we, Tina?” I nodded shyly.

He handed my mother her purse and lowered his head a little. “Thank you so much for that. You are a lifesaver.” My mother said and off we went back home to our little place.

From then on, we walked to this café every morning. “Good morning, Miss. Nice day?” We were greeted.

Mahinder, the older of the two, brought us our lassies. We chatted; we smiled; we left our bag. We waved goodbye from far away and hello the next morning.

It was like a glass wall had been shattered.

On our last day, we said our goodbyes, and Mahinder put his hand on my shoulder, “Your mother is a good woman. You are lucky. You will come back, yes?” And so, we did the following year.

I feel my mother had acknowledged his presence and dignity in such a simple and subtle way and through that, he had somehow come alive in our presence. “I see your goodness,” she said when she handed him the bag. And he rewarded her with that never-fading smile.

Many years later, when the tsunami hit and killed over 230,000 people as it raged on the shores of Thailand and Sri Lanka, leaving never before seen destruction behind, I observed my tough and strong mother on that day after Christmas, watching the news under a winter blanket on her sofa, tears streaming down her face.

“Oh God,” she said. “This is terrible. Those poor people.”

And then, with a voice so quiet I had to lean in, she said, “I hope Mahinder and his brother are alright.”

Nothing else has ever taught me about our common humanity in a way this kind of traveling has. We are all connected, cut from the same cloth, feeling the same emotions, and having the same hopes. We know this, we were taught this, but when we feel it in our bodies, it comes alive.

Read 15 comments and reply