A couple of days ago, I decided to go on TikTok for the first time.

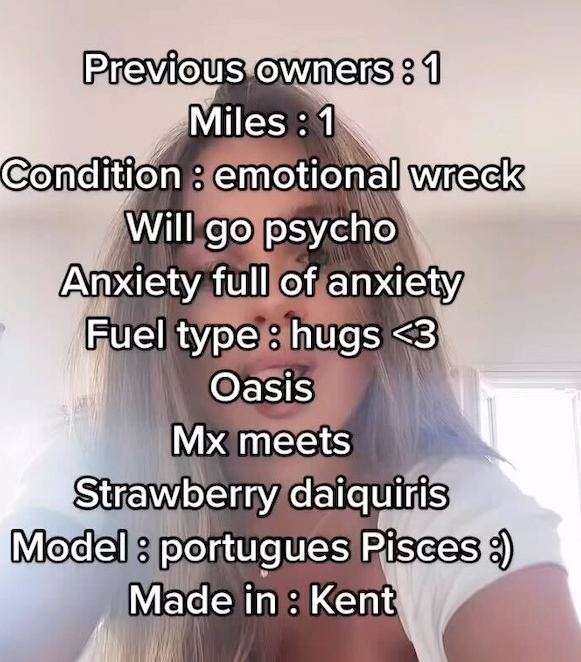

I know, I know, I’m late to the party, but stay with me. As I scrolled through video after video, I began to feel strange. There was a woman wanting to dress up as drywall for Halloween so maybe he’d put a fist in her. Another stating that her mouth makes a sound so the right thing would go in. I was disturbed and mesmerized at the same time. Who are these women and why do they think objectifying themselves is humorous? Then, just when I thought I’d seen enough, a video of two 20-something women crossed my feed. They could have been my daughters: young, attractive, and seemingly happy. As they danced to the tune of “Let’s Groove” by Earth Wind & Fire, one of them pointed to her friend’s derriere as the following advertisement flashed on the screen:

Miles:…

Previous owners: 2

Year: 2003

Make: Canadian

Model: Brunette

Stickers: 0

Fuel type: Alcohol

I scrolled on. Another video. This one showing a lone female. She turned herself 360 degrees as she danced, allowing the camera to record her from all angles:

Previous owners: 2

Condition: used

Year: 2002

Make: Hispanic

Model: Mexican

Has been crashed but is very reliable.

@clara.alvessxClearly love this dance ? #fyp #carsoftiktok #foryou #mx #uk #BurberryTB♬ Let’s Groove – absolutesnacc

I watched numerous others, same music, young women rating themselves as if they were used vehicles. That evening, I asked my daughter whether she has seen this trend on TikTok. “Don’t take it too seriously,” she said. “It’s just a joke making fun of dating profiles.”

But I couldn’t stop thinking about it. My brain kept replaying the images. As I lay in bed, I felt disturbed and sad by what I had seen. I needed to understand if I was overreacting to a silly meme or if my reaction was appropriate to something insidious, slipping just under my radar. The next morning, I decided to “look under the hood.”

In 2017, an Audi commercial from China aired. A bride is inspected by her mother-in-law for reliability and standard. She passes the test, although she’s asked to cover up her cleavage. The tail end of the commercial flashes on a shiny red Audi. It’s an ad by Ogilvy and Mather Beijing promoting used Audis that have been checked out and certified for resale. The tagline: “An important decision must be made carefully.”

Needless to say, the ad received quite a bit of heat for comparing women to merchandise—dare we say…objectifying them? Why wasn’t it the groom who got inspected by the bride’s mother? Any teeth missing? How about down below? All parts in working order? No. Sadly, it was another woman who inspected the bride and deemed her acceptable for her man.

Let’s back up even further. In 2009, Susan Fiske, a Princeton psychologist utilized brain scans to show that when heterosexual men looked at pictures of women in bikinis, areas of the brain that normally light up in anticipation of using tools were activated, and those associated with empathy for other people’s emotions shut down. These men’s brains literally turned women from people they could interact with, to objects they could act upon. “They’re reacting to these women as if they’re not fully human,” Fiske said.

Objectification is the action of degrading someone to the status of a mere object. Those objectified, be they any gender, are denied autonomy, inertness, are interchangeable, without boundaries, ownable, without feelings, are reduced to their physicality, and lack the right to speak. Sounds harsh? These are the features of objectification, primarily in the sexual realm, identified by Martha Nussbaum, an American philosopher and a professor of Law and Ethics.

Let’s go back to the TikTok memes of women objectifying themselves willingly as part of a humorous take on dating profiles. One could say it’s a free world. Women get to show off and promote themselves however they want. They can celebrate their sexuality, post videos of themselves for the external consumption of whoever happens to scroll by. It’s their prerogative to do with their image whatever they want, to invite one-night stands, have sex for the sole purpose of pleasuring their bodies and satisfying primal needs. Many would say it’s an act of empowerment.

But, if objectifying one’s self is empowering, why don’t we see women who wield their real power doing it? Why don’t we see Oprah, Brené Brown, Glennon Doyle, or Liz Gilbert posting memes showcasing their bodies? Yes, these women are privileged. They are educated, highly intellectual, and empathetic humans. They are successful in their own right and have no need to objectify themselves on social media to gain attention or followers. But we don’t have to come from privilege to know, deep down, that comparing ourselves to cars is not owning our sexuality, it’s selling it. We are not unique when we follow the latest trend on any social media. We turn into blank canvasses for others to paint upon.

As a woman, I find it disturbing that some of my sisters see nothing wrong with comparing themselves to used cars, see nothing wrong with saying they have been previously owned by their partners.

Let’s take this a little further. What happens when a nine-year-old girl, on the playground with her friends at recess, sees this meme? What does she know about objectification and feminism, about misogyny, the centuries old fight for wanting to be seen as equal, rather than as compartmentalized body parts or a sexual object? She is on the fringes of developing her identity. She is highly impressionable to messages that are disseminated consistently and incessantly by social media. Unless she has attentive caregivers, parents, or other adults teaching her she has innate value as a female human being, what she will see in this meme is the thousands of views and likes and maybe think: that’s what I have to be or do in order to attract a boy.

What about the 11-year-old boy on the playground? What takes place in his malleable brain when he is repeatedly fed, through social media, memes of women voluntarily comparing themselves to objects? When he hears women, not much older than him, putting themselves up for sale, saying they’ve had previous owners and that they are used? Joke or not, the brain processes this information and projects it out into the world.

The men in this boy’s life are a significant part of the solution. It is their responsibility to stop the cycle of objectification—to change the male culture of how women are regarded and treated. It begins by teaching and modelling empathy. Connecting emotionally. Using dignity in language when speaking with and about women.

Just because science has proven that men tend to sexualize more then women, it doesn’t mean they are powerless to change their primitive reactions to visual stimuli. Our brains have the capacity for change. That too has been proven by science.

I wonder, who is the gatekeeper of TikTok? Is there a team of editors who are responsible for the content that goes out? Are they educated in the ways of how social media affects the brains and behaviours of its most vulnerable users? Our children? When I did some research, I found out that TikTok’s review of which videos violate its guidelines is now automated. It uses content moderation technology. A human never has to see what videos make it through for mass consumption.

Has feminism taken a major dive without anyone noticing? Are we really okay with young women objectifying themselves and passing it off as self-empowerment? Thanks to social media and its highly sexualized content, are we becoming a culture of women so desensitized to objectification that we now do it to ourselves? I feel deeply affected by the fact that these trends grab the attention of hundreds of thousands and go viral.

I realize that TikTok is here to stay, and that one article on Elephant Journal won’t make much difference in how women choose to portray themselves on social media. I also realize that I come from a different generation of women. It could be that today’s feminism is not the feminism of my youth. But when women become their own perpetrators, the problems of objectification become more insidious and harder to fight. Let’s teach our children to look beyond the images of bodies on their phone screens. Let’s pause the video with them and talk about that person’s humanity. That they have a mother and father, sister or brother. That they too have dreams and hopes and fears. Let’s deprogram ourselves from the brainwashing we receive through social media and realize the innate value within us all.

Read 20 comments and reply