Reactivity is something that all of us, from one time or other, have suffered from.

Many of us can experience it several times a day, I know I have at times.

Reactivity can be something that drives our behaviours in ways that are often negative to us. In my life, there have been lots of things that I’ve reacted to, and I’m sure many people react to them, too, which rarely leads to positive outcomes. Yet, I can now see, after several years of practicing mindfulness is that reactions, whatever the cause, are experiences we can learn from if we pay attention.

Reactions can be important teachers.

There are the obvious and immediate things that can cause reactivity to occur in us. To give one example, my personal kryptonite is the driver who cuts us up in traffic. A reaction arises that we’ve been wronged in some way, our pride taking a hit and we get angry. We may shout at them as if they can hear us, some of us may even try to cut them up in return, putting both us and other road users at risk. We can feed that fury as the driver disappears into the distance, and the rage can simmer long after the incident has taken place while taking the shine off our day, week, or even months.

When I first stepped into the mindful path, it was reactions like these that first struck me as being me who was causing myself to feel pain when I really didn’t need to. Yeah, the bloke who drove like a lunatic was dangerous, but I don’t know what his life is like. Maybe he’s rushing to get to his mother’s death bed so he can say some final words to her or hear hers? Maybe he just drives like that because it gives him a sense of power when he has no power over the other areas of his life? The point is, we don’t know what their issue is, what causes that behaviour, and more importantly that is all out of our control anyway. But, if we practice mindfulness and learn to watch our thoughts and feelings without engaging with them, we can see that we cause ourselves to suffer when we follow the reactions that arise.

We can experience first-hand that if we don’t let these things go, then there is some kind of misery. Better still, we can slowly learn through mindfulness practice that what is in our control is whether we follow these thoughts or not.

Recognising this is, in my experience, one of the most immediate benefits of mindfulness because I can now recognise these reactions when they’re appearing without judging myself, and then, I can rapidly let them go. Which means, other than a brief effect, there is no real impact on my day.

It’s a lot easier to practice this successfully on the reactions that come up from our exchanges with people who mean little or nothing at all to us. Reactions to deeper hurts with people whom we care about are somewhat harder to let go of as they emerge. Maybe there’s a friend who has let us down time and time again, or a family member who has treated us badly for years, or even a manager who promoted a lazy colleague instead of us when we’d done all the hard work. There’s a myriad of different ways that people who are close to us can cause reactions in us to arise. Sometimes, these reactions, if we just go with them without pause, can have a profound impact on our well-being for long periods of time.

Yet, the practice of recognising that a reaction has appeared because of someone close to us, and stepping away from it, is no different from the way we handle it with people whom we don’t really know or like. We recognise that an emotion is arising and that there is a desire to do something, even if that thing is to simply follow the rage in our minds and then to observe it all without getting involved or berating ourselves for having those thoughts. We keep watching until the point where it all starts to fade away of its own accord.

Ajahn Sumedho, a student of the well-known Thai mindfulness teacher Ajahn Chah, and at the time an abbot of a Buddhist monastery himself, with decades of meditation behind him, has described how, upon visiting his parents in his late 50s, he was surprised to find that he was reacting to them like his much younger self. Not following the reactions that come up, especially those that we’ve spent our entire lives perfecting, is one of those easier said than done skills. It is incredibly difficult and we will often get it wrong while reactivity will take us over. It really is the work of a lifetime (even if you’re a Buddhist monk).

Finally, there are the subtle reactions, our likes and dislikes, that are part of our experience that may not even hit our radars at all. But if we don’t know they’re there, we can’t work with them, and we definitely can’t learn from them.

For me, after I’d been practicing mindfulness for a while, I started to realise my likes and dislikes were reactions in themselves. I started to see, like all other reactions that I followed, that they took something away from my life and made me feel less at peace with what is.

For example, it was fairly early in my meditation practice, maybe toward the end of the first year, and I was following a guided meditation and the thought “Please just stop talking for a minute or two so I can meditate without interruption” came up and I followed it. I sat there irritated for the remainder of the meditation suddenly not liking the style, huffing to myself that the gaps between the guidance were not long enough for me to really get into the meditation.

The session ended and I felt highly irritated. Then, I started to get annoyed in other guided meditations and the calm they had previously given me was lost and I started to be bothered by the fact that the instructors didn’t match my desire for the perfect guided meditation. Yet, the meditations hadn’t really changed, but the thinking around them did. The reactions that I had followed unmindfully meant that I was dissatisfied and lost in my head rather than in the moment of living life.

This is the problem with following reactions and why learning to step away from them is such a big part of mindfulness: our reactions don’t make our lives better. Shouting at ourselves and letting our blood pressure go through the roof doesn’t stop that driver from acting the way he did, but it hurts us. If we start screaming at a friend or a family member whom we perceive has treated us badly, it might make them pause, but what it also does is upset us and make a decent resolution, between us and the other person, harder to come to.

Yet, if we can become the witness to any reaction, learn how to watch them and see them for all they are made of without the need to engage with them, then not only does it bring us peace with what is but it gives us the opportunity to learn from what has occurred in our mind.

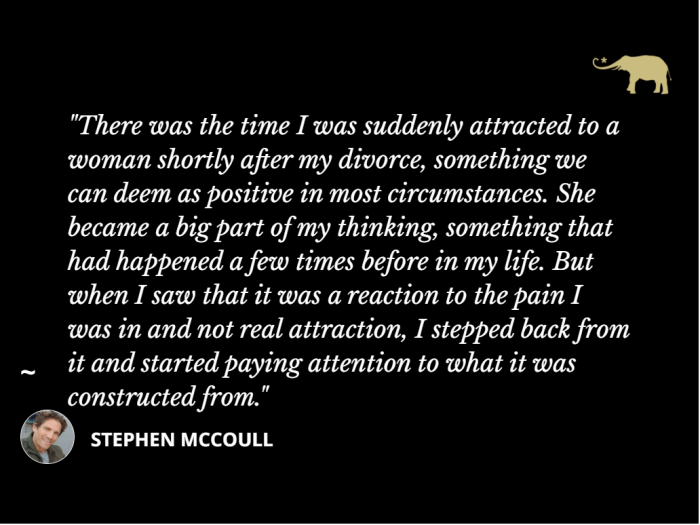

Some of the greatest lessons I’ve learnt have come from stepping back from reactivity and watching it with interest. For instance, there was the time I was suddenly attracted to a woman shortly after my divorce, something we can deem as positive in most circumstances. She became a big part of my thinking, something that had happened a few times before in my life. But when I saw that it was a reaction to the pain I was in and not real attraction, I stepped back from it and started paying attention to what it was constructed from.

I saw, almost in that same instance, that I wanted a relationship with the person because I didn’t like myself. I needed to be distracted from that discomfort, and I also wanted to be validated so that I felt like I was good enough. That lesson meant that, rather than getting embroiled in the thoughts in my mind and with the woman, I could decide to work on myself instead. I can learn to accept who I am, who I have been, and in the end, to like myself rather than use a relationship to block things out, which, in turn, meant after some time that I was finally in a place to have a healthy relationship.

In addition to big lessons, there are small ones, too, that can also improve our lives.

When I realised the reactivity to the guided meditation was actually the cause of my annoyance and not the meditation itself, I just watched it and I realised that it just meant that I was ready for the next step on my journey: unguided meditation.

I began to sit without instruction and my practice really did leap forward. But you know what? Once I let that reactivity go, I was able to go back and occasionally indulge in a guided practice, and now, because I am able to accept things as they are, I really get something out of those meditations when I do them.

It’s not always easy to even recognise there is reactivity in us, let alone to cease the desire to follow what comes up. But if we can start to withdraw from those sudden bursts of emotions, we might learn a thing or two and start to feel a bit more content with life as it currently is.

The question is: can you become aware of what triggers you and use that recognition for improvement?

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 4 comments and reply