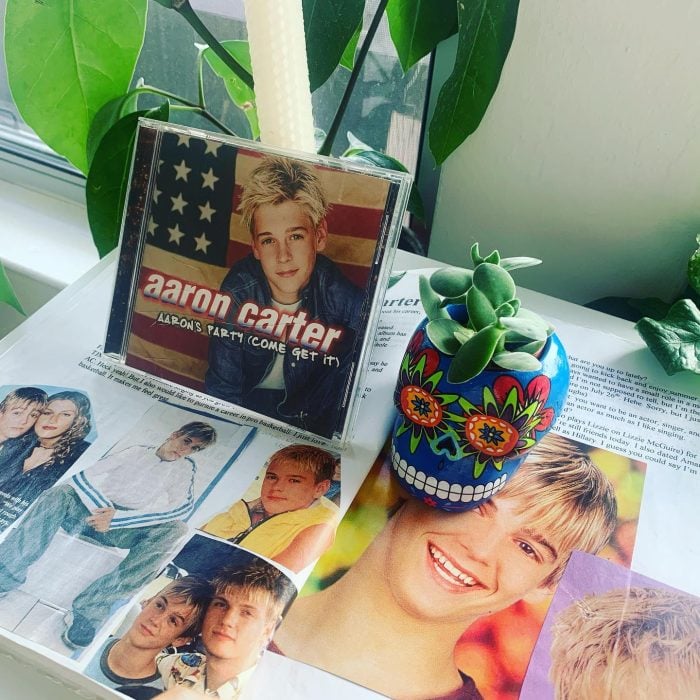

He was one of my first celebrity crushes back in the early 2000s.

I bought every one of his CDs, which I listened to on my boom-box and clunky disc-man attached to giant fuzzy headphones. His face was on the binder I took to school. I wrote him a fan letter once; his manager responded to it with a signed photo that I kept for years.

Aaron Carter.

Though the pop star fell off my radar for many years, in 2017, I was excited to see that he was making music again. His new sound reminded me of Justin Bieber’s 2011 resurrection from teeny-bopper to more edgy. I was also happy to hear that he’d come out as bisexual, bringing some exposure to the underrepresented topic of male bisexuality.

One thing I did notice in Aaron’s more recent videos was that he looked a lot different than how I remembered. A quick Google search brought up articles about how he’d gotten into drugs. I remember overhearing passengers at the time (back when I drove for Lyft) joking that he looked like he had AIDs.

There was so much judgment and derision in their voices when they said it. And thinking about it saddens me now—because it brings to light how many of us hold such contempt for those battling addictions.

It seems as if the minute a person gets slapped with the addict label, they become unworthy of our empathy. In our unspoken moral hierarchy, those able to cope with their pain in socially acceptable ways stay inside the realm of humanity. Those unable to get cast onto a lower plane. We almost seem to write them off as another species entirely.

That “us versus them” mentality feels so polarizing. Such a binary conceptualization of those with addictions as certain types of people far removed from our lives only further stigmatizes them—making it, I imagine, more difficult to step forward and seek help. I think about how much less likely they are to return to the land of the healthy and whole when they’re no longer regarded as equals.

Addiction and mental health struggles are rising amongst all demographics, but rates are particularly high in the LGBTQIA+ community. According to American Addiction Centers, “Gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents are 90% more likely to use alcohol and drugs than their heterosexual counterparts.”

Additionally, a study noted that some subgroups of the LGBTQIA+ community “have even higher rates of abuse. The group with the highest drinking rates in the LGBTQ community was bisexual women, 25% of whom reported heavy drinking.”

The thing about the judgment that gets me is that every person is capable of becoming addicted to a habit, behavior, or substance. As author Leslie Jamison has written, “It’s important not to lose our grip on the notion of disease or its physical mechanisms by defining it too broadly, but it’s also true that everyone has longed for something that harms her.”

I think we sometimes forget that so many turn to addiction as a response to unhealed trauma—which Aaron’s family had so much of. Addiction killed his sister Leslie, too. (She passed away in 2012.)

People often resort to drugs when trauma gets to be too much. It piles too high. The load they’re carrying surpasses the tools they have to deal with it—so they reach for whatever’s there.

A character in a story I once wrote, who struggled with addiction, summed up what compelled him to begin using:

The effect was guaranteed. It was one never offered by the people around me—complicated and ever-changing and verb-like as they are. And being complicated and verb-like and ever-changing myself, I couldn’t provide that same effect to myself either.

And so I turn to them when the next existential torrent sweeps through. Needing them feels infinitely safer than needing any person.

Another one writes:

The past is a giant boulder that picks up more and more momentum with time. The hope is the idealistic novice; the expectation the practical and ultimately stronger swaying force.

And it gets bigger and stronger, gaining mass with every experience, while you keep getting smaller. Hope flies like a foolish ineffectual firefly in the face of it. Superficial. No matter how strongly felt, it just can’t match the more deep-seated expectation backed by years of experience.

Higher rates of social stigma, minority stress, and family rejection all contribute to the increased rates of mental health difficulties that may lead members of the LGBTQIA+ community to abuse substances, according to psychologist Dr. Laura Saunders.

I myself struggled with my alcohol use as an adolescent and young adult. I went from proclaiming as a kid (after trying a sip of my dad’s beer when he wasn’t looking) that I would never drink because it tasted so bad— to, 10 years later, throwing back shots at frat parties and drinking to cope with difficult emotions.

But it was a vicious cycle because the depression and anxiety I was unconsciously attempting to alleviate through alcohol were only made worse by its consumption.

In Aaron’s case, it feels also important to note that while bi people of both genders face greater discrimination than gay and hetero individuals, for men the stigma is more pronounced—or they tend not to be believed (in contrast to women, whose sexualities are seen as more fluid). A bi male friend I once had said he was frequently told that he was just “gay and in the closet.” When he first came out as bi, people used to question whether he was just dating women as a way of fitting in.

Aaron himself claimed that his girlfriend left him after he came out to her as bisexual. The lack of understanding, and even prejudice, are on display in movies and TV shows such as Insecure, where the character Molly breaks up with Jared—a guy she’d been interested in until then—after finding out he’d had a “gay experience.”

What Aaron reached for to ease his own pain sadly resulted in collateral damage to the people around him. He had a volatile relationship with not only his older brother Nick Carter but others as well. He and his fiancé had broken up and he’d just lost custody of his infant son. What he reached for pushed people away.

I think the tragedy of this is that what hurting people desperately need is to have people close. What they need is community. Community is what heals. It’s what keeps the wounded in the land of the living. It buffers them from falling into the darkest depths of addiction.

As Aaron’s friend put it in a video a few days after his death: “He was very lonely in his own mind. He wanted to be hugged. He wanted to be loved. But one person on their own couldn’t give him that.”

Consistent presence can open the slats to let in one ray of hope, and then another—until maybe one day, the room fills fully with light. Or the person in recovery grows accustomed to that dance between the light and the dark. The dance replaces the perpetual darkness that once dominated their life.

Emotional healing makes a sneak attack on addictions. It strips them of some power and reallocates it to allow space for the individual to reemerge, vital and intact.

I wish Aaron had gotten the help he needed. I wish someone or something had intervened. Rest in peace to him and everyone else who’s departed this Earth having lost the battle with their demons. No words can ever be enough to fully capture the heartbreak of that.

Read 7 comments and reply