I hesitated for a long time before opening the TED talk that was sent to my inbox.

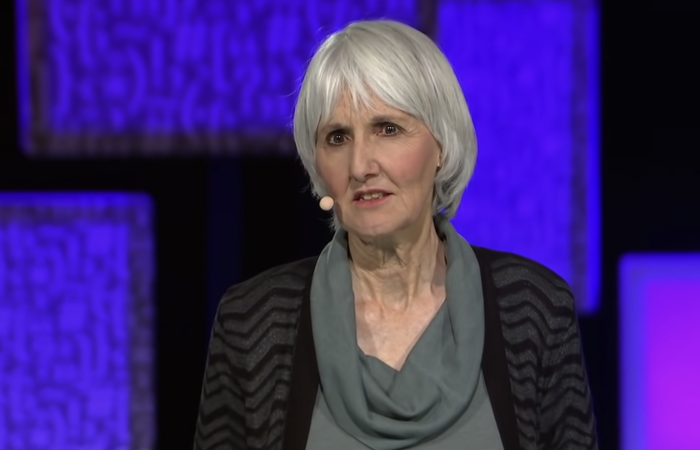

It was a talk given by Sue Klebold, the mother of Dylan Klebold, one of the two shooters who committed the Columbine High School massacre.

Honestly, I don’t like thinking about school shootings or other dark subjects. Most days, I’d much rather live in a place of denial and forget that bad stuff happens, especially to children.

I even debated not opening the talk at all. But, in light of the recent shootings in Nashville and Texas, and because this horror seems to be commonplace in America, I thought it was time for me to pay more attention, try to understand why such atrocities happens, and learn how to inhibit them from ever occurring.

And when I did finally listen, I was thankful for Sue Klebold’s insights.

I’ll confess, I wanted to dislike Klebold, maybe even despise her. I wanted her to have funky, black fingernails and no teeth and to be the epitome of wicked. After all, she did raise a monster who murdered 12 students and one teacher and wounded 24 others on April 20, 1999, in Littleton, Colorado.

Yet, Klebold’s character is the antithesis of everything I expected or wanted her to be for my understanding of that horrific event. She is bright, articulate, and well-intentioned.

Listening to what she had to share left me questioning how this madness could have happened on her watch or originated from inside her family.

Since the tragedy, Klebold has been trying to answer these questions herself. She has studied suicide prevention, questioned experts, spoken with survivors of loss, and explored the critical juncture where mental health issues and violence intervene.

Today, she is a tireless advocate, committed to the improvement of mental health awareness and intervention. Her message for us is this: we can’t go on believing that stuff like this happens to someone else and that it can’t happen to us.

With that being so, she tells us that we need to be vigilant and aware of the warning signs when someone in our community is struggling and is a danger to themselves and others.

In her book, A Mother’s Reckoning: Living in the Aftermath of Tragedy—all profits are donated to research and charitable organizations focusing on mental health issues—Klebold doubles down on her hard-learned lessons and shares her unfathomable journey as a mother.

I realized that whether or not I believe Klebold is the right messenger or deserving of our empathy, she has much wisdom to impart.

Here are five crucial lessons I learned from the mother of one of the Columbine shooters:

1. Normalize talking about suicidal thoughts.

Talking about taking our own life is a taboo subject within many social circles, religious institutions, and families. In our culture, it’s seen as crazy or a weakness to think of ending our own life. Yet, contemplating our existence and examining our purpose in life separates us from other animals and makes us human.

As a community, we can de-stigmatize talking about suicide and remove the shame associated with those discussions.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, close to 20 percent of high school students report serious thoughts of suicide, and nine percent have attempted to take their lives. Additionally, suicide is the second-leading cause of death among people aged 15 to 24 in the United States.

We can ask questions such as: Do you wish you could just die sometimes? Or: Have you ever thought about suicide? We can do a better job of listening and getting comfortable with having these types of conversations.

The experts tell us that talking about suicide and talking about depression won’t encourage suicide. On the contrary, openly discussing our mental health, reaching out to those who are struggling, or obtaining help if we are struggling ourselves can discourage it from happening.

Families, schools, community centers, and police forces need to accept that talking about suicide and depression does not make matters worse.

2. Ask open-ended questions.

Klebold has said that she wished she had known how to ask her son open-ended questions, instead of yes or no questions. She admits to checking in on him regularly but never being able to reach him. She says her questions were either leading or closed-ended and did not invite conversation.

Often, when we reach out to someone who is suffering they resist talking to us and may appear to disengage. They may also assure us there is nothing wrong. It’s important, however, that we listen to our intuition if it is telling us something is wrong and we keep trying to make a connection.

Asking open-ended questions can open the door to communication and let them know their ideas and thoughts matter. This type of questioning may dissuade them from isolating themselves.

Some examples of open-ended questions begin with these phrases:

What would happen if…

Why do you think…

I wonder why…

How can we…

Tell me more…

In what way…

What would you do about…

Why do you think…

What’s your best guess…

3. Systems fail.

In the months and years before the Columbine shootings, every social system that was involved in the shooters’ lives had failed to see the warning signs—the families, school, juvenile court, and the police force all missed the red flags.

Klebold relays that her son had been suffering from severe depression for two years before the shootings and that he had firearms hidden in his bedroom. He wrote disturbing journal entries and school papers that indicated his mental challenges. Additionally, he had been arrested and was ordered to take part in court-appointed counseling.

Still, his suicidal condition went unnoticed, the guns were never found, his mental illness was undiagnosed, and he was never treated. Unfortunately, when looking back on these incidents, there were warnings, but they were only taken seriously after the fact.

Each social system operated individually instead of collaboratively, and there was a tendency for each of them to rationalize the signs away.

4. Murder-suicide and depression.

Sadly, many of the horrific shootings that have taken place were carried out with the shooter’s intention to end their own life. There isn’t clarity as to why this action isn’t taken alone and why it involves harming others as well.

It’s believed that many who have committed these horrific acts had been suffering from clinical depression and other mental illnesses for some time and that due to their illness, especially when it went untreated, their thinking became impaired and irrational.

We know that receiving support for depression and being alert to the warning signs of depression and suicide are integral parts of thwarting the harm done to oneself and others.

We all may feel sad from time to time, but major depression is significantly different from the sadness that comes and goes.

Those experiencing a major depressive disorder may experience feelings of hopelessness, worthlessness, apathy, restlessness, sleeplessness, a lack of concentration, anxiety, guilt, and thoughts of suicide. The most striking symptom is the lack of interest in activities they once enjoyed and a significant change in their personality.

Those who are at risk for suicide, according to the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, may talk about feeling trapped or being in unbearable pain and being a burden to others. They may increase their use of alcohol or drugs, act anxious or agitated, behave recklessly, sleep too little or too much, withdraw or feel isolated, be prone to mood swings, show rage, or talk about seeking revenge.

Those at serious risk may make a plan, write a will, or give away personal and sentimental items.

5. We can’t explain away the conditions.

Despite the number of casualties, the highest rate of school shootings in the world, and an increase in firearm-related violence, the United States government has done little to address this epidemic. Unfortunately, there is a lack of political cooperation between the right and left parties in our government.

Klebold tells us that stricter gun laws and more access to mental health services would certainly help.

It is her firm belief, however, that the best way to prevent school shootings is to not ignore or explain away the conditions that tend to surround these hateful incidents.

Most school shooters have encountered peer or social rejection, weathered bullying, have resentment about the bullying, and don’t have the social or coping skills to handle these difficulties.

Their attacks are typically planned out and their spiteful views tend to be broadcasted on their social media platforms or written in their class essays.

Lastly, certain characteristics of a school itself make them more or less vulnerable to a shooting event: an inflexible culture, unbalanced discipline, leniency for disrespectful behavior, and a code of silence.

Klebold tells us that among the many letters she received after the shootings, there were letters from former students who expressed their surprise that a school shooting hadn’t happened at Columbine High School earlier.

And while these qualities do not justify committing such extreme violence, they do paint of picture of what we can look out for and how we may counteract harmful conditions.

If you or someone you know is dealing with depression or suicidal ideation, please reach out for help:

The Suicide and Crisis Lifeline is a 24-hour toll-free phone line for people in suicidal crises or emotional distress. Call or text 988 or visit their website.

~

Please consider Boosting our authors’ articles in their first week to help them win Elephant’s Ecosystem so they can get paid and write more.

~

Read 8 comments and reply