This is an excerpt from Keith Martin-Smith’s book When the Buddha Needs Therapy.

~

When we hold our opinions of things lightly, and we look to be discerning rather than judgmental, we can observe that it’s raining outside, that my partner seems especially moody, and that we don’t appear to be doing enough to address climate change.

Or I can judge the stupid f@$king rain outside, hate that b^%ch of a partner and her irrational moods, and wonder how so many stupid people can be doing so many stupid things to ruin the planet.

One perspective invites curiosity and an openness to dialog and change, the other is the prelude to war. You might be correct in your discernment of the world or the people in it, but your attachment to that discernment, known as judgment, fuels internal and external division. Remember that you cannot be liberated and opinioned at the same time, but you can be liberated and discerning. Opinioned and enlightened are mutually exclusive states of being. When you know something in your being, as opposed to just your mind, you don’t need to argue about it or defend it with self-righteousness, attack, vitriol, contempt, shaming, and derision…

…There are very few times when one can make a categorical statement that is true all the time, in all places, and in all times.

This is one of them.

No one has ever gotten angry who didn’t care first. Anger can only arise when you care about something that has been violated in some way, even if it’s just in your imagination. It might be the space in front of your car on a highway, your perceived level of respect from your boss, your love of your country, or your love of your kids. Even the clearly mentally ill person shouting on the corner cares about the topic of his rant.

Anger only ever arises because there is care first. Which means the first thing to arise, before anger, is caring. First caring, and then we make the conscious or unconscious choice for anger. That is kind of amazing if you think about it, because how often do you feel the deep care driving your anger? Probably not very often, at least in the moment, although sometimes in hindsight the care can be clearly seen.

The trouble with anger is that it’s messy, noisy, and often counterproductive. We have a saying in martial arts: an angry warrior is a dead warrior. I can’t tell you how many times in my Kung Fu school I’ve been sparring my students and watched them get angry. When this happens it is then very, very easy to beat them for the simple reason that anger is messy and imprecise. It isn’t relational. It can’t listen. It’s closed and hard.

When we get angry, our amygdalae produce fight or flight hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline. This raises the pulse, narrows the field of vision, lowers blood flow to the neocortex, and puts more blood into the limbs. It makes us, in short, dumber and stronger. Against a trained fighter, uncontrolled anger is as obvious and as effective as a four-year-old having a temper tantrum. You literally see the “lights go out” in their eyes as their consciousness dims. And in you swoop to take them off their feet.

Yet it’s not much different outside of the ring, Anger is allowing ourselves to be taken away from what’s present on a deeper level—care, and maybe some fear or vulnerability.

It’s worth taking stock of how well our anger has served us. We might be angry about the state of the environment, or what our spouse said to us last night, or about trans rights, or about gun rights.

Can you name the times your anger has made things better and gotten you more of what you were wanting? What about the times your anger made things worse, and ended up getting you less of what you were wanting? My guess is most of the time anger has not served you well if you’re honest with the scorecard. Certainly, great anger doesn’t tend to leave us closer to what we’re really wanting.

The next time you feel anger you probably won’t notice it until afterwards. But once you realize you were recently angry, ask yourself a few simple questions:

>> What did I care about?

>> What outcome did I desire?

>> Did my anger help me get it?

>> What else might I have said or done?

If you’re the type that never or seldom feels anger, you might not feel safe with that emotion (usually because of your childhood experiences), and so instead of anger you’ll feel an intense sense of collapse or self-judgment, which is just anger facing inward—f@%k me rather than f@%k you. This tends to be on the parasympathetic side of the fight/flight/freeze response, but it operates the same way. Your unconscious choice, or reaction, is to move away from your care and into self-judgment and numbness as a way to not actually feel the care that had to arise first.

The realization and expression of care, instead of anger or collapse, can profoundly impact your life. The reason is neither anger or collapse expresses any of the actual vulnerability that is under the reactive emotion.

Feelings are information. When you get angry or you attack yourself/collapse, it means you care about something. It might also mean you feel vulnerable, overwhelmed, or scared as well. Anger covers that up so you don’t have to feel the vulnerability, the care, that’s driving it. If you feel the care when it arises, you can choose a response rather than reacting with anger or collapse.

When I met Junpo Roshi (my Zen teacher) I was in a very – let’s be polite and say “dynamic” relationship. It was one that had me constantly fighting with my then-girlfriend. I once came to him, dismayed at how often and how badly I was getting triggered into explosive anger.

“You must care a great deal about her,” he responded.

This completely floored me—it was immediately obvious and immediately deeply confusing. “Is the anger working?” he then asked. I admitted it wasn’t working. “Maybe you should try something different,” he suggested.

If you can feel the caring and the vulnerability, what arises instead of anger is something much more powerful: clarity. Clarity, unlike anger, keeps a channel open to the heart and to the cortex, which means you’re in touch with your care and with the fact that a boundary may need defending. You gain the power of anger—focus, intensity, single-mindedness. But you lose the downsides—emotional blindness, impulsivity, unskillful defense, prefrontal cortex shutdown. You gain everything and lose nothing, because you get to choose your response to your care rather than have it chosen for you.

No one has ever made you angry or caused you to collapse. You have always chosen that, consciously or unconsciously, every time. Anger and turning away are our choices, and when we’re willing to take radical responsibility for those actions we stop being victims and instead become the creators of our own lives, fully in control of life as it is in this moment.

Your boss can’t make you angry, nor can your kids, your spouse, the “other” political party, the nature of the world, or your childhood. The person in the White House has never made you angry—nor has the jerk who cuts you off in traffic. Your abusive father didn’t make you angry, nor your narcissistic boyfriend. The patriarchy can’t make you angry, nor can people who are “too woke.” No one has ever shamed you or caused you to turn away, either. You can’t be shamed. You can’t be made angry. You can’t be made to collapse. Only you can do this, only you and only you alone, again and again and again, forever putting the blame in the wrong place: outside of yourself. You react unconsciously rather than choose your response, wisely and compassionately.

The key is there is a choice point—your choice point—even if you can’t see it that proves no one has ever made you angry. Let’s see why.

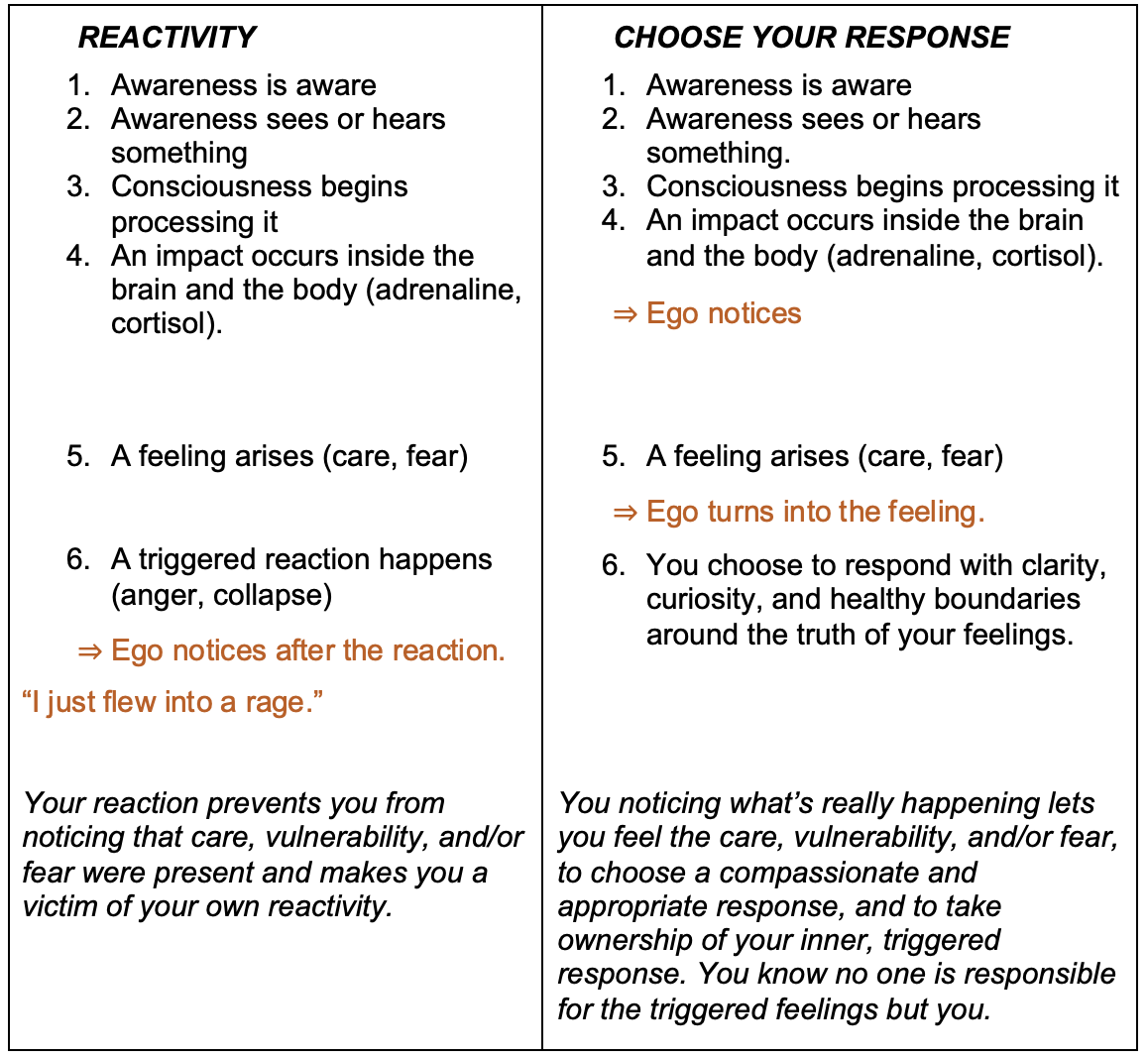

Most of the time it seems like we just fly into a reaction. Meditation offers a deeper way for us to uncover choice and have more impact on ourselves than psychotherapy alone can offer. Junpo, for instance, had a huge advantage in spending six years in a monastery, where he learned to quiet his mind. In the stillness he allowed there, he was able to witness the moment when he would get triggered. Rather than “flying into a rage” or becoming a victim to his own reactivity, he’d notice that a trigger had fired inside of his mind. Awareness, deeper than ego and deeper than relative consciousness, would watch it arise. As I already discussed, Zen training then teaches you how to remain unreactive to the trigger. You wait until the trigger has passed, bypassing it until you can back into life without reactivity. Zen teaches you that this is the goal—to bypass.

This is better than reacting, and we’d be lucky if most of the world did this. But as Junpo realized after he became a roshi, there’s no wisdom, no self-understanding, and no healing without choosing to turn directly into the trigger and to face it, head-on. Therapy can help us understand what’s causing the trigger in the first place, something meditation cannot do. Instead of letting the trigger arise and fall away, we can notice it arise and then choose to turn completely into it.

First, let’s understand better what happens when we get triggered—and from a spiritual perspective rather than a psychological one. First, we need to go back to our definitions around consciousness and awareness.

Consciousness, you’ll recall, is the entire self-system of the ego, the unconsciousness, and the self-awareness of all the components of the self. Our consciousness can be expanded or small, spiritual or profane, and it strongly colors how we experience the endless and undifferentiated flow of reality which, to remind you, doesn’t much care what you think or feel about it—it just goes on being real.

Awareness comes before consciousness. Without awareness there is nowhere for consciousness to arise. This might just sound like a bunch of hot air unless you’ve experienced it, and I won’t waste time or energy trying to convince you. Hopefully some of the practices at the end of this book can help to give you that experience for yourself. For now, let’s just presume that I’m telling the truth, and that awareness is aware and that it is always here, at the root of your consciousness. If that is true, then it would follow that getting triggered would look something like this:

Notice there is no stopping the triggered response. But with meditation practice, you can learn and experience that there is more space between sensing something and our reaction to it than you can imagine. It’s only microseconds between a stimulus and a reaction. Yet to someone who has a meditative mind, microseconds can literally pass like minutes. In the concentration meditation offered in Zen, you can do much more than simply witness your emotions arising. You can turn into them, follow them down to what is really going on. And then everything that arises is a wonderful teacher: Jealousy, anger, shame, lust, and envy (just to name a few emotions) can awaken you rather than be something in the way of your precious spiritual self.

>> What does it feel like to take full responsibility for your life as it is, in this moment?

>> What if no one and no thing was responsible for your life but you?

>> What if it was also true that the stuck places in your life are, to this point, not your fault?

>> Can you experience the feeling of full responsibility of your entire life, right now, without collapsing into anger or shame?

If you take full responsibility for your life, you may likely experience a great deal of fear, because your life is suddenly your own, without exception. If you recall from the previous chapter that fear is really just excitement, then what might you actually be excited about inside of all this freedom? Perhaps it’s the terror of knowing that you have more control over your own life than you ever imagined possible, and that you have the power to recondition yourself in whatever way you can imagine. Yet your shadows often stand in the way of this process.

~

Please consider Boosting our authors’ articles in their first week to help them win Elephant’s Ecosystem so they can get paid and write more.

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 7 comments and reply