Blech.

Trust me, I vomited in my mouth just a little with the title of this story. How incredibly cliché it sounds, right?

Lessons I learned as a teacher.

Like, the classic story of a teacher going to class to teach and frame younger minds, to nurture and shape the lives of enthusiastic and not-so-enthusiastic kids, and then lo and behold, it’s the teacher who comes away having learned valuable lessons from his/her students.

Dun dun dun…or is that the tring tring tring of a violin playing in the background?

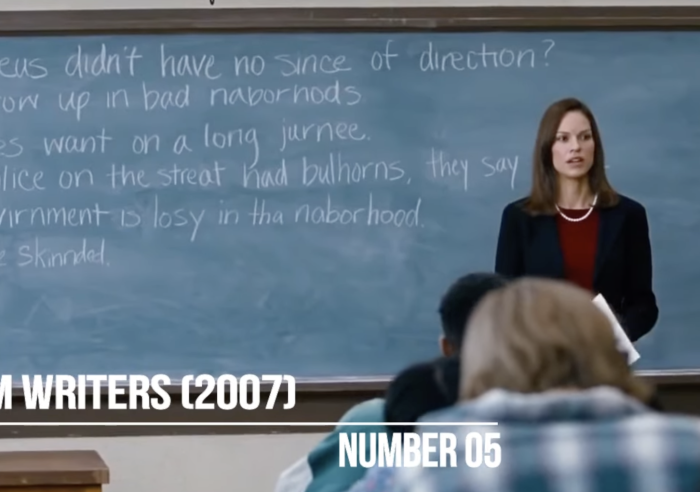

You’re probably recalling all those dramatic movies where the plot—well, there is no real plot in those teacher/student stories— always goes one way or the other.

Plot one is the students are a bunch of whiny, entitled brats who don’t give a crap about the classroom, much less believe that there’s anything to be learned. And when your parents give you a Mercedes for your 16th birthday, I guess I would wonder similarly. Or the kids are so poor and come from crime, drug, and violence-ridden backgrounds that poverty is their only real reality and these already down-and-out kids have so many adult issues to deal with on a daily basis at home that a teacher and classroom are the least of their priorities.

But, enter said teacher or professor. After 90 minutes of the kids making life miserable for the teacher, the latter valiantly teaches the kids a valuable life lesson and all’s well, that ends well.

Plot two is when the teacher is a drunk and indifferent jerk. More often than not, he (and it’s usually a he) drinks too much because he is almost always a failed athlete who got injured and his career ended, or all the fame and money meant that he lived life too fast and burned out, or his indifference is the result of a love affair gone wrong. Either way, he doesn’t really give a crap about the game he once used to love and live for. Well, of course, he does, but that’s the story he is comfortable with peddling for now.

That is until his high school comes calling. They have a sucky team of players who have lost every game they’ve played for the last three years—they’ve become the ultimate joke of their town. But the players themselves are talented, except they have no direction or drive or ambition, all of which only this teacher will be able to guide them with. Essentially, they need this drunk and indifferent teacher to come in and save the day.

So, enter jerk teacher or coach who doesn’t really give a damn about the high school team—until he does. And, almost always, the loser team, under the guidance of the now brilliant teacher, finds a way to make that final basket or that final kick that wins them whatever championship they’re playing in.

All’s well that ends well.

The teacher, again, becomes the one who learned from his students.

Again, I know what you’re thinking: such a bloody cliché title. But this title really means something to me.

I’m not and never have been a “born teacher” It’s not something I’ve ever wanted to do. Life and circumstances and that little thing called “needing to feed oneself” meant that I ended up teaching. And a year into it I was pretty sure that I was just not cut out to be a teacher. It just wasn’t me.

Teaching was not my vocation or something I felt I had to do.

It was a job.

And as a professional who takes her job seriously, I worked hard and prided myself on doing a good job. I never ever slacked off. I put effort into making my classroom interesting and informative. I remembered my days as a student and what I looked for in a teacher and the kind of things that would’ve made the classroom more interesting and interactive for me, and then I incorporated those ideas into my own classroom.

And I think, over the years, I’ve done a fairly reasonable job of it.

For the past six-plus years, I’ve been a teacher in classrooms where the medium of instruction is English but where English is a second language to my students. And I’m not a science or math teacher where it’s all about numbers and formulas, or where language (native or second or third language) plays a secondary role.

I teach Journalism and English Creative Writing. I teach students who are non-native English speakers how to write stories, plays, and essays in English. I don’t just teach them how to write in a language that’s not their own but I also make them write and perform their material in an auditorium and in front of their peers. Yep, my creative writing kids write one-act plays in English and they act in them. My journalism kids write feature stories and publish a magazine at the end of the semester.

It cannot be easy. As much as these kids love the process of creation—and they love writing—thinking, writing, and performing in a different language is not easy.

But over the years, I have seen how relentlessly these kids work. I’ve never, and I mean not ever, had a student complain about the long hours and the challenges they face. Every piece of writing that they submit goes through at least three different iterations. I push them hard, I’m strict with their grammar, and I tell them if their ideas are stale, boring, or overused, and weeks-worth of painstaking pages of writing get returned to them with comments and red lines all over.

You may be thinking this is how it is with all professors and all writing classes. And I agree. The difference though is that when I did the same with students in countries where English was their first language, the blowback was severe. The attitude was whiny. The complaints were aplenty.

But where I’m teaching now, every comment I make to these kids is proof of my personal interest in their work. All of my red scrawls on their submissions are a matter of pride that they happily show to others. At the end of the semester, they thank me for caring enough to make them write the same story, the same play, the same essay multiple times and push them each time to create something better.

They told me once that they’d never had a teacher like me before. They’d never had a teacher take this much interest in their writing.

It was such an Aha, come-to-Jesus moment for me.

I realized then that I had never had students like them either. There was no anger, no irritation, no pushback for my demands. It was genuinely and 100 percent a humbling teaching moment for me.

At that moment, the teacher had become the student.

My biggest takeaway was that it doesn’t matter what we choose to do, what matters is understand that if we have to do it, we should do so with a good attitude, with the right spirit. We can find the positive in the negative and stop complaining.

As a college professor for over a decade, I now realize that we don’t actually have to love something to do it well. And that we can feel extremely gratified and satisfied doing it day in and day out, even if it’s not our first choice in life. That regardless if we love something or not, if something needs to get done, we do it. And quit whining about it.

Teaching is still not what I want to do long-term or thought I would be doing. That hasn’t changed.

What has changed is that I realize I don’t need to be an asshole about it anymore. I could choose to see the good in what I had to do.

My students taught me that.

~

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 31 comments and reply