Cultures and civilizations around the world recognize the fact that human beings have a limited time here on Earth. In order to cope with this, we’ve invented some pretty crazy myths to explain where we’ll end up when we’re dead and gone.

Grand celestial kingdoms, endless battlefields, and bizarre cubes under the ground are just some of the weird realms we’ve dreamt up. But what’s even stranger is that many of these afterlife myths share almost identical beliefs with those of other cultures despite them existing thousands of miles and sometimes as many years apart.

So, let’s find out about the elements these ancient beliefs share on the similarities in afterlife myths across civilizations.

God

God is in almost every religion. In every myth with creation at its heart, there exists one or more supreme beings. Whether they’re immortals, hammer gods, or sexy water goddesses, they all have one thing in common: They are better than you.

And with afterlife myths, this goes even further, because not only did they build you and create all that you know, but they also get to decide on where you go when you die. This is a theme shared by many different societies. It doesn’t matter where you are in the world or what time period you’re from, whether ancient Egyptian, Iroquois, Indian, or modern Scientologist—you all believe that you were put here by an entity more powerful than you, and when you depart, it will be on their terms.

So, why did human beings gravitate to this way of thinking?

Let’s face it, we’re a pretty egotistical species, so surely it should have made more sense for us to believe that we were gods and that we decide where we’ll go when we die. Just think about it: Humans created fire, we invented the wheel, we can control and manipulate other creatures for our food, transport, and into fulfilling our adventurous or pleasure-seeking needs. Based on this, we could have been forgiven for appointing ourselves as the gods.

How come there are no religions that believe human beings have a say in where they go in the afterlife?

Why is there free will in life, but not in death?

Instead of placing humans in charge of their own afterlife destiny, we assumed something more powerful was behind all that we knew. That is why the answer may be lying in the middle of the Amazon rain forest. Evidence of mankind’s belief in the afterlife goes back a heck of a long way, at least 50,000 to 100,000 years, and so far, almost every human culture we know of has some kind of explanation for what happens when we die, with one notable exception: the Piraha.

This group just doesn’t give a rat’s ass about what the rest of the world is doing; the Piraha are an indigenous tribe that inhabits a remote region of Brazil. The Piraha lack words for numbers and colors; they have no form of social hierarchy or a leadership structure; they do not measure time, and one of their firmest beliefs is a total opposition to coercion (i.e., they don’t go around telling people what to do). Furthermore, the Piraha culture is solely concerned with the things that are directly experienced.

Jesus, as a concept, has been introduced to the Piraha several times in their history, but they reject him due to the simple fact that nobody who believes in Jesus has actually seen him. They are a very literal society who believe that if you haven’t experienced it, then they are not interested. Basically, the Piraha base their lives on the mantra “pics or it didn’t happen.” So, unless you’ve experienced the afterlife and come back to tell the tale, you’ll have a hard time convincing a Piraha there’s any kind of existence after you die.

But, how does this explain how afterlives and gods were created?

Elsewhere, is there a connection between the invention of God and afterlives?

Again, in societal hierarchies, as we said, humans are pretty egotistical and love telling folks what to do. Hence, if you’re looking to cement your power as head of a tribe or community, what better way to do it than to invent an afterlife and claim that you have a direct line to the guy with the guest list?

Many leaders use the idea of God for controlling a restrictive afterlife to retain and increase their power. Psychologists, philosophers, historians, and neuroscientists are united in the belief that this preys on the fact that humans are biologically predisposed to believing in something bigger than themselves, with the possible exception of the Piraha.

Most humans cannot accept what we see is all there is. There has to be something more. There has to be an afterlife, a creator, and a purpose for all of this. And guess what? This belief in a higher power and an afterlife is hardwired into every single one of us on a deep level of our consciousness.

According to cognitive scientists, humans are born believers regardless of their nationality, upbringing, or education. This brings us to a rather amusing conclusion that whether you say you believe in God and the afterlife, or you don’t, is actually irrelevant. Hilariously, this is because, according to science, it may be the atheists who really don’t exist.

Fire

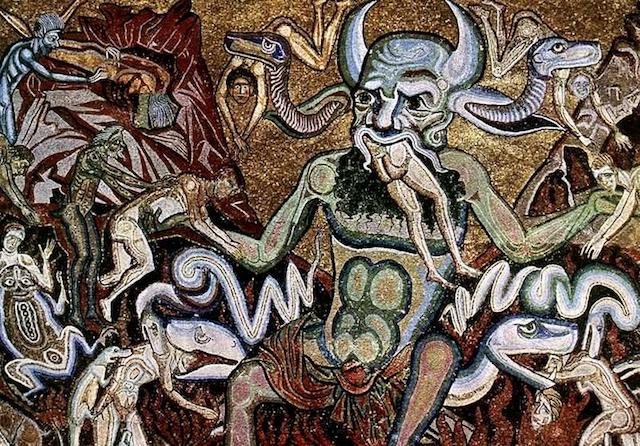

God was a pretty heavy topic to open with, so let’s take a look at something simpler: Fire. The idea of burning for all eternity in a world of fiery pets is commonly attributed to the Christian idea of Hell, but for some reason, the fire seems to play a role in many different afterlife myths—despite it being somewhat essential for cultured human beings to exist. We use fire to cook, toast, to heat our homes, but if you see flames after you die, you’re almost certainly in a really bad place.

The Islamic afterlife of Jahannam sees its residents dragged through fire, being forced to wear clothes that are on fire, having their organs burnt in front of them, and having their skin burnt off entirely—only for it to be regenerated and then burned off again just for fun.

The Greek afterlife myths also speak of a fire, so does the Egyptian afterlife myth, and the Christian concept of purgatory is supposedly filled with fire as a means of cleansing oneself of the sins which prevent your ascension to heaven.

So why does man really associate the uncontrollable nature of fire with death and destruction? Was it perhaps linked to the idea of burning our enemies alive to remove them from Earth?

Intriguingly, some religions go in the opposite direction and use water as their tool to inspire fear of the nether world. New Guineans believe that their underworld was beneath the ocean and so do members of the North American Navajo tribe. They believe in a journey across water to reach the afterlife. It’s also a surprisingly common theme, as you may know from the Greek tale of the boat man and the river Styx; but this is an idea shared by the Italian Etruscans who, instead of traveling by boat, believed that they would be ferried to their afterlife of Elysium on the backs of sea horses and dolphins.

So what made some civilizations choose fire to represent their afterlife and others choose water?

Were they linked in some way by a shared experience of a natural disaster? Or are we humans simply more inclined toward pessimism with even the life-giving properties of fire and water used against us for religious purposes? I am not sure, but I do know that when I die I would love to try the Italian thing with the sea creatures.

Music

Music comes in as number three on the bizarre similarity between many different myths and religions. There is the idea that the good afterlife is located somewhere high up in the sky, whereas the bad people are sent deep underground to somewhere dark and terrible. Obviously, this may have something to do with the fact that underground caves are dark and occasionally terrible, and clouds are super-duper pretty.

But is this enough to explain the sheer number of religions that have adopted this idea?

Ancient Mesopotamians believed that the dead went to live in a subterranean world known as the “dark earth,” and they thought that every hole and cave could potentially be an access point. Other examples include the Central American Mayans who said that the souls of the dead went to an underground world known as Shi bali. The Greenline Inuit believed in an underworld called Sedna, and the ancient Chinese believed in a Hell consisting of 18 levels beneath the earth. Then we have the Igbo people of Africa who believe that their dead traveled deep underground to live inside the womb of the goddess Allah.

Then there’s your typical fancy-pants, fun-time kingdom in the sky, which is thought to be the location of the good afterlife by everyone from Vikings and Eskimos to Christians and Wiccans. All of these vastly different religions placed their positive afterlife above our current plane of existence, both literally and figuratively, and so far we have not been able to find a single myth which states that when you die, you get to go live underground with the mold people.

If you know of any, please tell us in the comments below.

What we have found are various groups of people who believe that heaven lies neither up nor down. However, the native-American Papago and Pima tribes thought that there was a place to the east where in death you’d be free of hunger and thirst. Other Native American tribes said that their heaven was somewhere out to the west as did the Polynesians and European Celts.

So, it seems that regardless of their differences, most religions agree that heaven is not a place on Earth despite what that 80’s Belinda Carlisle song might have led you to believe. The Abrahamic religions of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism believe that humans are judged based on their actions during life, after which they’ll be sent to an afterlife which represents their moral purity.

If you’ve kept your wiener clean, wore a hat on Thursdays, or done whatever other crazy business your God asked of you, you’ll go to the good kind of afterlife—and if not, you’ll go somewhere bad forever.

This idea is nothing new, and it has formed a key part of many ancient afterlife myths including those of ancient Egyptians and Greeks. In each of these religions, your morality is determined by a god or goddess and once they’ve made their decision, they can send you to the appropriate afterlife. A judgment can be made without the involvement of a god, and it plays a huge role in the reincarnation myths of Buddhism and Chinese religions. Within these belief systems, those who resolve the negative karma of their past actions reincarnate as a lucky person, or they escape Earth permanently and head to a higher plane of existence.

However, if you are a bad person, you will become trapped in the endless cycle of life and death on earth destined to live out your days without ever knowing what’s on the other side.

Reincarnation

Reincarnation beliefs are shared among all the major Indian religions, and they can be seen in many tribal religions of the world—in places as far and wide as Australia, Siberia, South America, and Eastern Asia. Mostly they share the same idea; that it’s only by resisting certain behaviors and temptations that you can escape constant reincarnation and reach the nirvana where “Smells Like Teen Spirit” play for eternity and everyone gets to wear oversized flannel shirts.

Isn’t it weird that all these religions share the belief that you must live life according to certain rules in order to enjoy a pleasant afterlife? It doesn’t do much to dispel the idea that religion was created for no other reason than to control people.

How did so many separate groups of human beings come up with the same idea of using moral judgments as afterlife entry criteria?

And are there any civilizations that reject this way of thinking?

Sure. The earliest Jews and Mesopotamians believed that the afterlife was the same for all people regardless of your actions, and the people of Polynesia thought that your destination in the afterlife was down to your class, with commoners and upper classes retaining their status after death. However, for some religions, the idea of Heaven and Hell is replaced by something far worse.

Eternal War

Eternal war is the description of a bad afterlife in both the Aztec and the Norse religions. The dead move on to either a world of endless war or paradise depending on the whims of their God and whether they died in battle. Vikings believed that half of those killed in combat would continue to fight alongside Odin after death, whereas the others get to sit in a field and get drunk with the goddess Freyja.

But there’s no indication that Norse mythology used morals to determine which afterlife you got to, and what’s even more bizarre is that anyone who died from boring stuff like sickness or old age would head off to Hell.

The Aztecs had a similar set of dual destinations in mind for their heroic warriors, as their gods would either send them to a paradise in the east or to fight alongside their war god in battle. These warriors were joined by those who had sacrificed themselves and women who had died in childbirth as they were deemed equally honorable as fighters.

Similarly to the Vikings, the Aztecs also had little respect for those who were killed by old age and disease as people who died an unremarkable death were sent to Machlin, where you’d have to traverse through several levels of existence to reach the good levels.

These non-judgmental belief systems are perhaps explained by the fact that both the Vikings and Aztecs practiced brutalism. It’s easy to convince a group of warriors to give their lives in battle if they believe they’ll be rewarded for it in the afterlife. Tspothis ideology is something we’re all too familiar with in the modern age with people across the world sacrificing themselves every day to appease an extremist interpretation of their chosen religion.

But despite what your racist uncle says, Islam is not alone in suffering from this plague. Christianity, Buddhism, and Judaism have all been used by nut jobs to justify suicide attacks. In recent years, the simple fact is that you’re unlikely to feel as though you have a stake in this world if your daily experience seems inferior to what awaits you in death. And this belief has motivated everyone from the Aztec warriors and Christian Crusaders to modern day extremists into giving their lives while taking those of others.

However, it turns out they shouldn’t have bothered. They were all wrong because all of humanity shares one single religion.

~

~

~

Author: Nikhil Chandwani

Image: Wikicommons

Editor: Travis May

Read 0 comments and reply