Last October, I went to Louisiana to visit my brother and his son, Walker, who at that time had just turned five.

The first day I was there, the three of us went to a pumpkin patch in the swampy October heat, where my brother and I stood between haystacks and watched my four-foot-tall nephew hunt for the scariest pumpkin, before deciding on one so large my brother had to bend his knees a little to heave it in and out of the truck.

When the pumpkin was carved, with orange goop adorning the table, the floor, and our faces, it was still light out.

“Let’s light it in the bathroom!” Walker declared, so the three of us huddled in the bathroom. When my brother closed the door and lit the candle, turning the razor blade grin a bright orange, Walker cried Ooooh!, jumping up and down and rubbing his hands with a spooked delight.

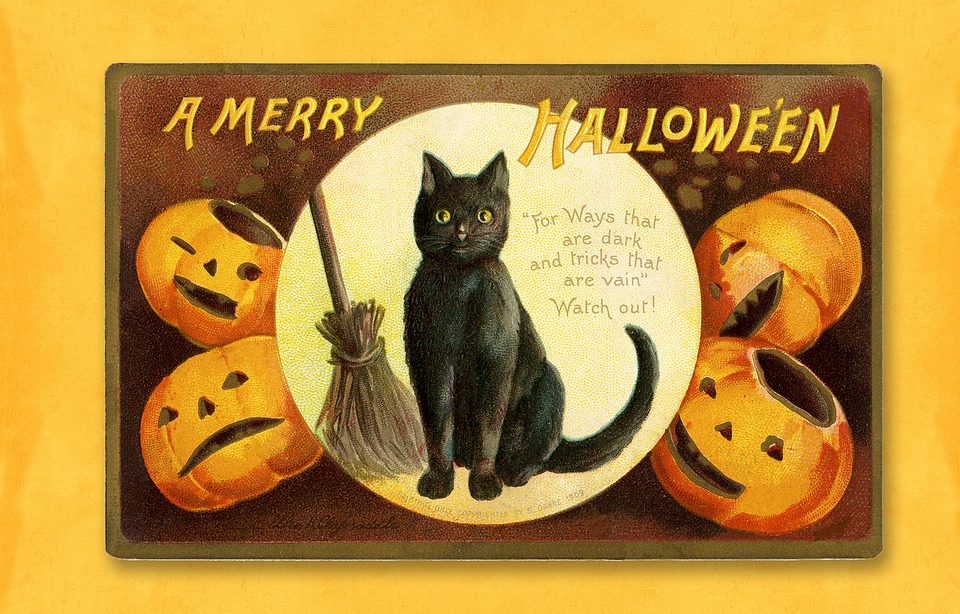

Halloween has roots in the Celtic celebration of Samhain, a feast held on November 1st, celebrating harvest, the end of the summer, and the eve of the Celtic New Year.

The Celts believed the veil between the living and the dead was thinner during this time, and lit bonfires to ward off winter darkness and trespassing spirits. In the seventh century A.D., Christianity adopted this tradition of Samhain into All Saints Day, or All Hallows Day.

Believing every prayer helped the safe passage of souls, poor people went door-to-door carrying carved, candlelit turnips to represent souls in purgatory. In exchange for bits of food, or treats, they offered prayers for the recently departed souls of a household.

Last October, the season of goblins and ghosts happens to have coincided with one of my own reoccurring seasons: a state of paralyzing fear which I have orbited around since a child. At times, I appreciated it as a sensitive strength; other times, I dismissed it as a good old-fashioned haunting. (I believe I am drawn to the practice and teaching of yoga partly because it is a practice that has given me tools to self-soothe.)

Still, when I become thoroughly spooked—the witches of my childhood replaced with the adult threats of the world—my response feels sometimes like it hasn’t budged: body frozen, eyes open, alert to every sound, every twitch of shadow in the corner, images streaming behind my eyes which I did not welcome and cannot bribe to leave.

These states are often prompted by larger events like the horror of the shooting in Las Vegas, which had happened three weeks before, but they can just as easily spiral into an obsession that is local, and this often feels inappropriate, shameful, childlike.

So this is how I showed up in Louisiana: part sister, part aunt, and part younger girl in the middle of a trance, a psychological holding pattern that I had not yet learned to break.

The second day I was there, Walker and I went out for a spin in the neighborhood, him zipping along on his scooter and shark helmet while I intermittently walked and ran behind him, telling him to be careful. I waited tentatively on the edge of people’s properties and watched my nephew pick up big, fake bones and touch partially-submerged rubber hands.

He walked right up onto someone’s porch and shouted at a life-size skeleton, clad in grey tattered robes blowing in the wind, “Hey!,” an incantation of authority, hesitation, and thrill. “Hey!” he yelled again, inching closer to the skeleton until he was right beside it, pieces of its cloak tickling his face.

I smiled at my nephew in his shark helmet, standing trustingly on a stranger’s porch, while I thought of everything that can go wrong on a stranger’s Louisiana lawn. I waited. When he had freaked himself out enough, he ran, giggling, back to safety, back to me.

On All Hallows Day, no one was safe from the dangers of a soul that was lost, slipping through the cracks of thin, Autumnal light. Part carnival, part exorcism, rich and poor were responsible for the prayers, masks, and treats that would usher renegade souls back to safety.

In 2018, Halloween remains a time when we acknowledge, mostly by way of campy outfits and Snickers bars, the shape-shifting of certain boundaries: the thin skin that divides the living from the dead, the collective and the private, the threats that will harm us from the ones that will make us brave.

It’s a time when a kid can tromp up to the front doorstep of a stranger’s house and shout “Hey!,” a time when unfamiliar doors swing open and new winds move through the trees. Children innately understand this time of year because, in a way, they are engaged in a 365 Halloween, a daily dance with fear that strengthens their own sense of self: letting the skeleton’s robes tickle their face so they can run like hell, back to the street.

My third night in Louisiana, I decided that if I couldn’t sleep, I wouldn’t bother getting in bed. I sat upright on the couch in the living room and said to my jangled, neurotic, terrified self, “Okay.”

For the next hour, I tried focus on my own spine, like a person in a storm holding on to a ship mast. Waves of gruesome imagery started to move through me, and when I noticed myself judging myself for it, I noticed that I wasn’t quite breathing. I would then deepen my breath again. I continued to panic, I continued to leave, and I continued to stay. I noticed as much as I could about my own rocking between story and sensation, story and sensation; my desire to slink up into my mental control tower where I could sit, frozen, repeatedly asking why I was this way and how I could make it stop.

Instead, the question I posed that night was, “What do you need?”

And the answer seemed to be: to continue to walk up to the scariest door of my experience and yell, again and again: “Hey!,” to throw myself against that door, to let the skeleton’s cloak tickle my face, to keep shouting at my own terrifying state until I understood that it wasn’t going to kill me, that in fact it was me, and that as much as it was here to haunt me, it had come to make me brave.

The poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote: “Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage.”

Rituals, at best, support our unedited and often irrational emotional expression and help us face our demons, until we relate to these demons with more intelligence and agency. This is where a tradition like Halloween and the practice of yoga cross paths in the night: as a body of spells and symbols, gestures that give art and commonality to the tough work of embodiment.

And what is it for you, dear reader, that lurks on the periphery of your attention? What fear are you certain that you know by heart, though you haven’t stopped once to soften it, to notice it, to breathe and allow it? What dragon in your life is waiting for you to act, just once, with courage?

I was called to bring courage to my practice this time last year, on the eve of a Pagan-Christian ritual that honors the flimsiness of doors and the need for a little magic. I let the truth of my thin skin flood in, placed the candle of my presence into that carved out place, and was filled with terrible light as some big, toothy, orange grin from inside me said back to all that I thought I could not stand: Boo!

~

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply