Language around “release” and “letting go” pervades the movement and healing world, but what do we mean by these words?

When language become habitual, our wisdom should guide us to step back and examine it carefully.

According to the Oxford Dictionary, the definition of release is: “allow or enable to escape from confinement; set free.” But before we focus on releasing tension, we need to understand why the tension, pain, or restriction is there in the first place.

During times of debilitating stress, or in trauma recovery, if we only focus on releasing tension we might be misguided. Tension does have a purpose, and we need to ask ourselves what that purpose is fulfilling.

Our bodies are held together with tensile integrity, also known as biotensegrity, and you might say that something similar can be said of our our psyches.

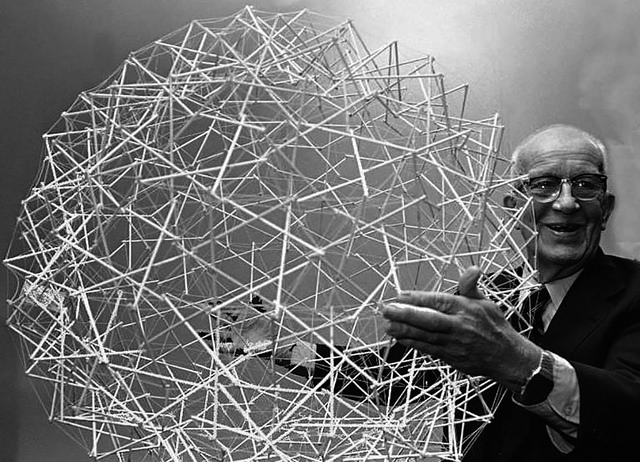

Tensegrity is a term first used in architecture by Buckminster Fuller. Here are some pictures of human-made structures built on the principle of tensegrity. Imagine taking one of the points of tension away. The whole structure collapses.

Biotensegrity is a new(ish) approach to understanding how bodies work based on the insight that we are primarily tensegrity structures, and our bones do not directly pass load to each other. Thus, forces primarily flow through our muscles and fascial structures and not in a continuous compression manner through our bones. In fact, our bones do not directly touch each other, and are actually “floating” in the tension structure created by our fascial network.

Zero tension equals collapse and, in the case of the autonomic nervous system’s response to threat, feigning death. The feign death/submit/collapse responses all involve a lack of tension in the body, going limp or hypotoncity. Our fascial system becomes like a deflated balloon. Our mammalian nervous systems decide what the most intelligent response might be and, if we can’t escape or fight back, we go limp so that we seem dead and less appetizing to a potential predator. Then, if the predator still decides to eat us, we get a big rush of natural pain killers and go numb so that we don’t actually feel the teeth sinking into us.

All very pleasant sounding, I know.

But getting out of a chronically collapsed state is very difficult because we actually feel lifeless, there’s no energy or tension to harness to mobilize ourselves. For this very reason, the habitual cue to release, soften, and let go in yoga classes is not useful for many trauma survivors. For a trauma survivor who escaped more psychological or physical harm by feigning death, constantly releasing tension can exacerbate this sense of collapse, immobility, and helplessness.

The fascial system mirrors the autonomic nervous system’s response to threat.

This threat response, which may have been a way of surviving in our past, can leave us in a state of learned helplessness today. Many trauma survivors need to feel their physical power, agency, and strength in order to access what the yoga tradition refers to as their “life force” (prana) and even, potentially, their repressed anger in order to learn how to break the cycle of collapse .

We develop coping mechanisms based on belief systems (about our family, relationships, whether or not the world is friendly or dangerous) that help us function in the world. This could manifest as walking on eggshells to avoid conflict and people pleasing in general, or working overtime because we fear if we don’t do more than expected, we will be fired. We develop these coping strategies based on what resources we have available at the time, what Sensorimotor Psychotherapy refers to as survival resources. Perhaps we had a parent who never made us feel we were enough, or a former spouse, or a former boss. Maybe we felt we had to overcompensate to get their approval, love, or even basic care.

Removing a survival resource too quickly can lead to us falling apart, leaving us unable to manage the day to day demands of life. When we find more creative resources, tools for self-soothing that help us feel emotionally and physically regulated (such as movement that makes us feel joyful and playful, expressive arts, hobbies that connect us to our communities) our out-moded survival resources slip away on their own.

As a result, the term “leaning into pain” as a way to clear the past out of our minds and bodies can be truly uninformed from a working with trauma standpoint. Many people with a history of trauma are either in a state of high emotional pain, physical pain, or emotional or physical numbness—or a combination of the two.

People with trauma histories already know pain very well. Trauma recovery is first about helping people improve their quality of life, right now—to feel less physical and emotional suffering—so that our nervous systems can start to regulate. Leaning into pain can send people outside their window of tolerance even further and create deeper neural pathways around the trauma.

Feeling all of our pain at once can be destabilizing for trauma survivors.The first stage of trauma recovery is creating a sense of safety and stabilizing both internally and externally. No true trauma recovery work can occur without these two things. The past will continue to feel like the present in our bodies and minds.

For example, when we take a hard, plastic massage ball and dig into the superficial layer of fascia, it sure feels like something is happening, but we are really just overworking connective tissue and breaking up fascial adhesions to the point that it creates more inflammation by causing damage to the tissue. To repair this newly created inflammation caused by overworking tissue, new adhesions are formed. So, it becomes a cycle of working hard to break up adhesions only to create soft-tissue damage that needs to be repaired again. We also might get a rush of endorphins afterward that leaves us feeling a little high, but we end up rebounding back into our tension even further. No lasting structural change or shifts happen.

If we focus on releasing both physical tension and emotional tension as the ultimate goal without asking the question, “What am I releasing into?” we might not fully understand the complexities of healing our bodies or our minds. We can only truly release when we have a sound physical and psychological container to release into. We don’t want to break down our physical or emotional containers. We need tension to keep us moving through the world. Otherwise, we might release and then need to habitually pull ourselves back together.

In restorative classes, cues like “just let it all go” can be problematic. Do we need to become puddles to relax and feel grounded? For many people with a history of trauma, feeling contained and able to mobilize the body is the path to recovery and a state of inner calm and safety. Idealizing this surrender can negate the fact that people might already be far too collapsed already.

Have you ever noticed how certain muscles that hold tension become the enemy in certain movement or healing circles or how compulsive behaviours (whether emotional eating, overworking, overspending, drinking, or spiritual bypassing—to name a few) become things about ourselves that we feel shameful about? But the truth is they were survival resources at one point that got us to where we are today. There’s an important reason for their existence.

Sure it feels good to release emotional or physical tension and pain. It can be extremely cathartic to let go. But what if the act of releasing and the highs of catharsis are just that, highs we chase and even get addicted to?

I’m not saying a little catharsis is bad. In fact, 90 percent of my clients cry during our first meeting but that’s because I create an environment or a container where it’s safer to let go. If I notice a client moving out of their window of tolerance, hyper-aroused or shut down, I know I need to find a way to help them ground and become more regulated. Rather than avoiding what we feel or letting it go, the trick is to move into difficult emotions, and without collapsing under the weight of them. Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn would describe this collapse as falling off your surfboard while you’re riding a wave. Dr. Peter Levine might use the example of a slinky opening so far and so quickly that it loses it’s ability to be springy and bounce back.

As yoga teachers, it might be helpful to consider replacing the concept of release and letting go with the idea of regulation in both our physical and psychological tensegrity. We need to focus on creating a sense of stability and safety both physically and emotionally—to sense our physical and emotional boundaries to have a safe and regulating container to release them into.

While many yoga teachers encourage more flexibility, softness, and openness, they might indirectly negate the need to feel stable and contained first. Lack of joint stability makes us feel more vulnerable and less resilient, potentially making us feel less safe out in the world. No wonder joint hypermobility is correlated with higher levels of anxiety.

Couple this fact with the drive to gain attention in social media by contorting our bodies in order to stand out, and we have a confluence of conditions taking us away from what our bodies really need.

We need to look more kindly on our physical and psychological tension as survival resources that have gotten us this far in life. Things we need to pay homage to instead of pathologize as maladaptive and needing to be removed at all costs. The tension is there for a reason. What’s the reason?

We can only let go of what has become maladaptive movement patterns, muscle tension, or psychological survival strategies when we feel safer and stable to do so, when the support structures are in place to contain the release.

We might consider blending the idea of bridging a need for safety with the ability to release and discover that alignment with our bodies’ and minds’ healthiest states will unfold with more ease and flow.

~

~

~

Author: Jane Clapp

Image: Flickr/Poet Architecture

Editor: Travis May

Copy Editor: Callie Rushton

Social Editor: Waylon Lewis

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 11 comments and reply