At the foundation of all our relationships is the ability to communicate effectively. When we are able to express our thoughts, feelings and ideas about each other, to each other, in a way that is understood by the other, we start to feel closer and more connected. In families, this need to be understood and connected is becoming increasingly important in a fragmented world in which support is hard to find.

However, ‘Communication Skills 101’ classes are rarely taught in schools and colleges and are, in general, lacking from our list of educational priorities. As a result, we have a tendency to pick up some bad habits that limit our ability to communicate and fully understand others. Without realizing it, we are often guilty of stifling what is exchanged in our conversations, which can lead to some dysfunction in our family and close relationships. For healthy communication in the family to be restored, it is fundamental to ensure that every person is heard, understood and valued.

When Communication Fails

Often communication is the vital piece of the family dynamic which needs help. When our partners don’t feel heart or seen, they often appear to be angry or ‘moody’, or shut down, it sews the seeds of resentment and frustration. The impact of an inability to not communicate effectively is far reaching. It is not uncommon for therapists to see poor communication and the feelings that ensure leading to ruptures in relationships, divorce and could even be traced to substance abuse and infidelity.

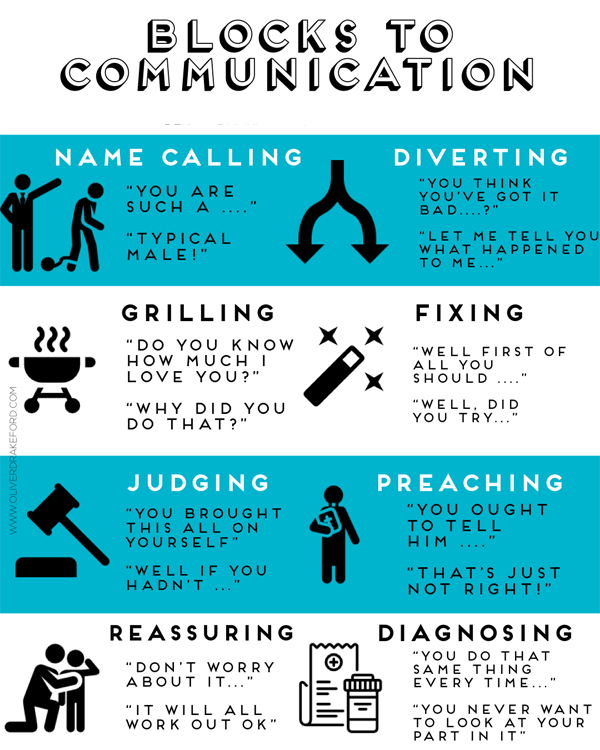

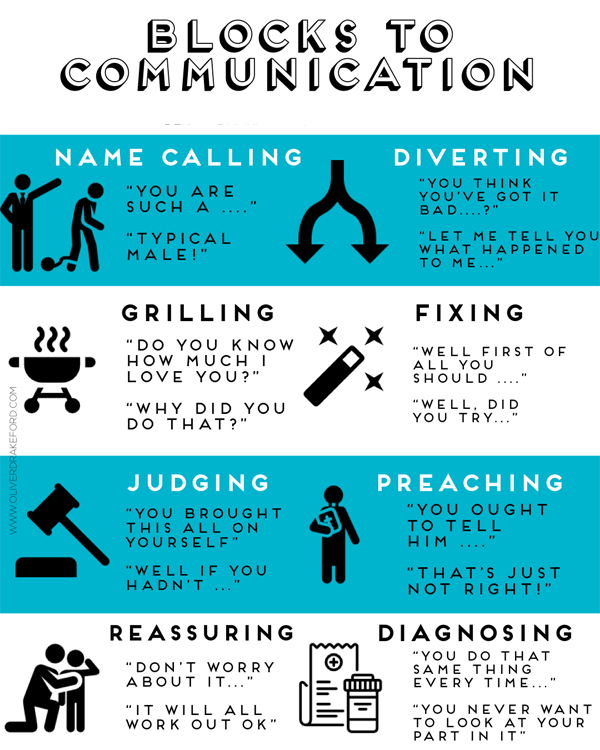

Demonstrating Blocks To Communication

Learning about blocks to communication is very helpful to understanding how to change, but often when we experience them in a deliberate way, it’s easier to make changes in our relatioships.

I devised an exercise in which I have couples and families participate in to highlight how the blocks to communication feel.

Partner A volunteered to talk for three minutes about what was going on in their life,

Partner B took the opportunity to deliberately throw in some of the blocks below at them at random times during the three minutes.

We then reversed roles and discussed what came up and processed what the experience was like for the person who was ‘blocked’.

Here are some of the thoughts and experiences I heard about in a session:

The Talker: “I was asked to speak for a few minutes about what was going on in my life. I actually had a headache and was talking out loud about why I thought it was happening”

Name Calling:

Definition: When the listener places a label on the person talking, communication is blocked.

The Block: “A headache? I think you’re being a bit dramatic”

Experience: “this was one of the first blocks I heard and it was just not what I was expecting to hear from my partner. It really threw me for a loop because I wondered if I was being dramatic for a second and if what I was saying was interesting to anyone in the room”.

Diverting:

Definition: The listener flips the conversation to another topic, or, more often, another subject:

The Block: “I have a headache too actually.”

Experience “I was totally baffled in how to respond to continue talking when I heard this. It was so jarring to have the conversation flip to my partner’s headache when we were talking about mine. It was a struggle to keep talking after this.”

Fixing:

Definition: When the listener attempts to fix the problem, it takes away from the speaker’s need to felt seen and heard. It becomes about the listener’s anxiety rather than the speakers experience.

The Block: “Well…. Did you take any ibuprofen?”

Experience: “In the moment, I quite liked hearing this, it felt caring coming from my partner. But when I tried to continue talking my headache, it was hard to continue. It did not help me expand the conversation and I suppose I felt shut down”

Judging:

Definition: A distinct judgment call on the other person.

The Block “You don’t drink enough water”

Experience: “This was a pretty blunt and aggressive comment that I had to breathe deep upon hearing. I actually don’t drink enough water, so felt really annoyed that someone else was telling me what I already knew. I also don’t like being called out on things, I got quite defensive.”

Preaching:

Definition: When the listener becomes the expert in the speaker’s topic, it takes away from the speakers need to express and feel heard.

The Block “You don’t look after yourself, get more sleep”

Experience: “This was not as impactful as some of the other blocks, but it definitely did not help me continue talking about what was going on with me. It limited my ability to continue talking for sure, it was more of a conversation ‘ender’.”

Reassuring:

Definition: The listener assures the partner of the eventual outcome of the problem. The Block: “It’s probably nothing and will go soon”

Experience: “This one felt really patronizing, like they were stating the obvious and not really expressing interested in me. I felt dismissed”

Diagnosing:

Definition: Putting a label on the problem is like putting the bow on the gift. It finalizes the problem and does not leave much room for exploration.

The Block: “You’re dehydrated and stressed”

Experience: “The fact that they were right was actually more annoying than if they were wrong. It didn’t help me to hear it in that way, and didn’t help me feel like what I was talking about was interesting or valid.

Grilling:

Definition: The listener attempts to fix the problem with a series of questions aimed to get more information from the talker.

The Block “How much water did you drink? Did you eat enough breakfast?”

Experience: “This felt like a quick fire round in a game show- it was HORRIBLE! I got flustered and couldn’t think fast enough — totally threw me off from what I was trying to convey. “

The Discussion

The exercise is often eye opening for anyone both parties. Couples and families gain some great insight into their own tendencies to block and were able to relate to experiences they’ve had when they have not been allowed to communicate effectively.

When you experience what it’s like to be ‘blocked’ like this, it makes it easier to notice how you communicate in conversation. I ask the families and couples I work with to think about if any of these blocks show up in their current relationships. I generate a discussion around who is more likely to ‘judge’ and who is more likely to ‘fix’.

Communication Unblocked

I encourage each member to bring awareness to their communication patterns as it often goes a long way in helping to improve family communication patterns.

A simple conversation with Partner A talking about headache might lead to deeper moments of connection and vulnerability. I encourage the use of phrases such as “Tell me more” or “Do you want to tell me about that?”, even a simple “Huh…” leaves the door open for more information to be shared.

Partner A: “I have a bit of a headache right now…”

Partner B: “Oh no! Tell me more… what’s going on?”

Partner A: “Well, actually, I think it’s because I am having a bit of anxiety about work.”

Partner B: “I had no idea you were struggling at work – I’d love to hear what’s been going on.”

When communication is improved, the family dynamic is impacted, often in an incredibly positive way:

Couples can be more intimate.

Adolescents feel more connected.

Families can feel closer.

Oliver Drakeford is a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist and sees individuals and groups for adult and adolescent counseling. His therapy office is located near West Hollywood and Beverly Hills. http://www.OliverDrakeford.com

Browse Front PageShare Your IdeaComments

Read Elephant’s Best Articles of the Week here.

Readers voted with your hearts, comments, views, and shares:

Click here to see which Writers & Issues Won.