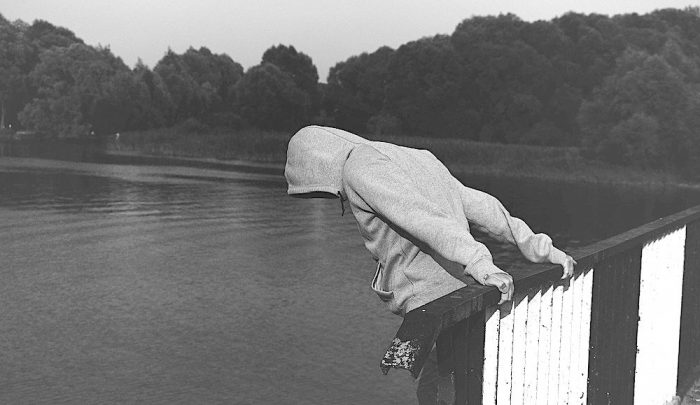

This week alone, I was told of three different suicides—three.

That’s a number none of us should consider “normal.”

While none of them were people I know, as a counselor, I’m trained to say, “How sad” and move on. Not because I don’t care, but because the amount of emotional news I handle every day doesn’t allow me to go deep every time. I hear a lot of sad things, so if I don’t move on from it, it’s not good for me or anyone else around me.

This week, though, with things happening that seemed back-to-back, I couldn’t just “move on.” I couldn’t turn on my happy face like a switch.

I’ve seen what suicide does to a family. My brother John killed himself when he was 21 years old. He had a good job. He had a great sense of humor. He was talented. He lived on macaroni and baked beans mixed together (like that’s a thing), played the drums, and listened to the “Legends of the Fall” soundtrack more times than anyone really should.

Before he killed himself, he’d just bought a house and was engaged. Everything seemed peachy on the outside. John had his happy switch on.

John had struggled with depression on and off for years, but he had always beaten it. He’d always been okay—until he wasn’t. Many times, the person who commits suicide is someone you’re least likely to expect.

What is it that takes a person from thinking about suicide to doing it? What can you look for to make sure that you see the signs?

I’ve studied and learned quite a bit about suicide over the years, and I’d like to tell you about some red flags that are not always obvious and exactly what to watch out for in order to help protect those important to you.

In honor of John (and so that you can remember this is about real people), I’m using my brother’s name as an acronym to help you remember.

J: Just ask clearly

O: Observe for changes

H: Help find hope

N: Now get connected

Just Ask Clearly

It can feel awkward—even embarrassing—to tell a friend or loved one that you’re worried about them. To avoid that feeling, sometimes we may tiptoe around the real question. “Hey, man. I’m worried about you. You don’t seem like yourself lately,” or “Hey, if you’re ever having a down day, call me!”

Those words are nice, but they are not enough.

Instead, say, “I really care about you, and I’m afraid you’re making plans to hurt yourself. Is that happening?” and, “If you were to hurt yourself, how do you think you would do it?”

There is a myth that talking about suicide or asking about plans for suicide will increase a person’s chances of hurting themselves. This is not true. Talking about it gives them a chance to get those feelings out. Knowing someone is listening and watching can make all the difference.

If a friend were to walk up to you with crutches and their leg in a cast, would you ignore it because you’re afraid that asking about it might make the leg hurt worse? You wouldn’t dream of avoiding the subject! You would want the whole story. Did they break their leg in a bathtub? Rollerblading with their kids? Saving a baby from a burning building? You’d want to know, right?

On a daily basis, you will meet more people in intense emotional pain than in intense physical pain. Sure, it’s not always as obvious as a broken leg, but often you don’t ask even if your gut tells you something is up.

Ask clearly and get details.

“So, it sounds like your plan would be to kill yourself by ____.” Do you have things to do that with?” Do they own a gun, have pills, or have too much time alone in tempting situations? If so, ask if they trust themselves with those things right now. The worst thing they can do is get mad, but that’s unlikely for someone in that frame of mind. If they do get mad, though, you can still have peace in your heart knowing you did the right thing.

Observe For Changes

You may think I’m simply saying, “Look for changes in the person.” And that is important. But the thing I want you to look for first is changes in their environment. The thing that differentiates those who think about suicide from those who commit suicide is what’s going on in their environment. What’s going on in their real life that is impacting things like stress, sleep, and self-worth? Those are the things that can push someone over the edge.

Here are some important changes that should trigger a “check-in” with someone who struggles with depression:

Lack of Sleep

If you want to really cause trouble, mess with someone’s sleep schedule. Someone who has been down and thinking about suicide, when sleep-deprived, often becomes the person who does it. Have they been out partying more than usual? Do they have a new baby? Are they consistently making social media posts at odd hours, like 3 a.m., when nearly all others are asleep?

Changes in their Schedule

Did this person just come back from a trip? Have there been major changes to their normal daily routine? Even things that seem like “good changes” to the outside world can sometimes cause a more extreme sense of high or low.

Loss of Loved Ones

Have they experienced a recent loss of any kind? This is especially worrisome if the loss was due to suicide.

Time of Year

Is it spring or summer? Most people think suicides are highest around the holidays, but that’s not true. Suicide rates spike throughout the spring and summer months. Like nearly everyone else, even those with serious depression have more energy in the warmer months and are more likely to find the energy to follow through with thoughts or plans they had in winter.

After changes in the environment, look for changes in the person:

>> Are they suddenly very calm and peaceful? If they are usually down and then seem content all of a sudden, that can be a sign that they have finalized their plans and have come to their own personal “peace” about it.

>> Are they giving things away? Are they organizing their home that is normally disorganized? I’m talking about completely unprompted changes—if they’ve been binge-watching “Tidying Up” with Marie Kondo episodes on Netflix, don’t worry about it.

>> Have they asked you to watch/take care of their pet or their kids out of the blue?

Look for changes that make it more likely for someone to hurt themselves. Not sleeping, travel, and the time of year all make it more likely for someone to turn “thinking about it” into “doing it.”

Help Find Hope

Remind them that life is worth living and help them find a specific reason they want to live. They should be able to say why they want to live for real—with supporting details! They might say, “I want to die at times, but I couldn’t do it because who would take care of my kids? I could never put them through that!”

It needs to be specific. In a counseling office, when someone is extremely depressed, the difference between the person who goes home after a session and the person who goes to a hospital for their own protection is based on one question: Can they explain in detail a reason they want to live?

Depression’s dirtiest trick is that it’s always lying. It tells people they are unwanted, unloved, and that it won’t get better. It makes things that are temporary feel permanent. It makes it hard to see things clearly, and everything is so dark that it’s hard to find a way out.

Your job as a friend or loved one is to walk in the darkness with a flashlight and say, “See that thing over there? You have more to live for than you think. Right now, you are tired, and you can’t trust yourself—you’re not thinking clearly. You may feel like you are, but you’re not. Will you promise me you won’t make any decisions right now? It will get better. Walk me through this: what do you have to live for?”

Help them think it through and find some hope for the future. Positive things that seem obvious to you are completely lost on someone who is truly depressed. Help them find some hope.

Now Get Connected

A connection is penicillin for depression. Staying actively connected is essential in protecting them from themselves and helping them to heal. Get them connected with a counselor, a psychiatrist, and real, consistent help.

Let them know they’re not alone, that it’s okay to take medication, and that the choice for them to hide at home has been revoked.

You love them too much and are about to become the most endearing (ahem, annoying) friend they’ve ever had.

There will be no hiding in the dark.

Pain is easier when it’s shared with others. Period.

I hope this helps you keep a more helpful eye on friends who need it. Depression and deception are master conspirators. If someone really doesn’t want you to know they are thinking of killing themselves, then most of the time you won’t.

But depression, as sneaky as it can be, will always tell on itself. It is a repeat offender and shows up in consistent ways. Knowing what to look for gives you the advantage, and that just may help you save someone’s life.

Read 2 comments and reply