While it seems a bit odd, I’ve spent a bit of time over the last few years contemplating death and dying.

Doing so seems like a pretty good place to begin if you’d like to live well.

In the West, we seem to have sterilized death and dying, relegating them to hospitals and nursing homes, as if we might somehow inoculate ourselves with immortality. Part of that, I think, comes from our fear of becoming dependent on someone else—needing someone to feed us, wipe our chins, maintain our hygiene, or even to remind us what day it is, or where we are.

We don’t want to think of ourselves as weak or dependent. I know I don’t. But in the face of my father’s declining health, I’m learning some important things.

I’m learning that giving care to someone else is, while exhausting and sometimes painful, is a privilege. And even though my father is still far healthier than many 86-year-olds, he’s needed more from me lately. He hasn’t expected it. He’s just needed it.

I’m learning that just being with my father, and the woman who has loved him for more than 60 years, is sometimes what’s most important. I’m learning I don’t have to chatter words of comfort, hovering over him to see what he needs, or to reassure my mother everything will be alright.

I’m learning that fatigue makes me more irritable than I would like, and that from time to time, I need a few minutes or an hour to breathe and re-center myself. I don’t just need that for my own well-being, but so I’m able to return to him with a renewed zeal for the little bit of care I can give my dad or reassurance I can offer my mother.

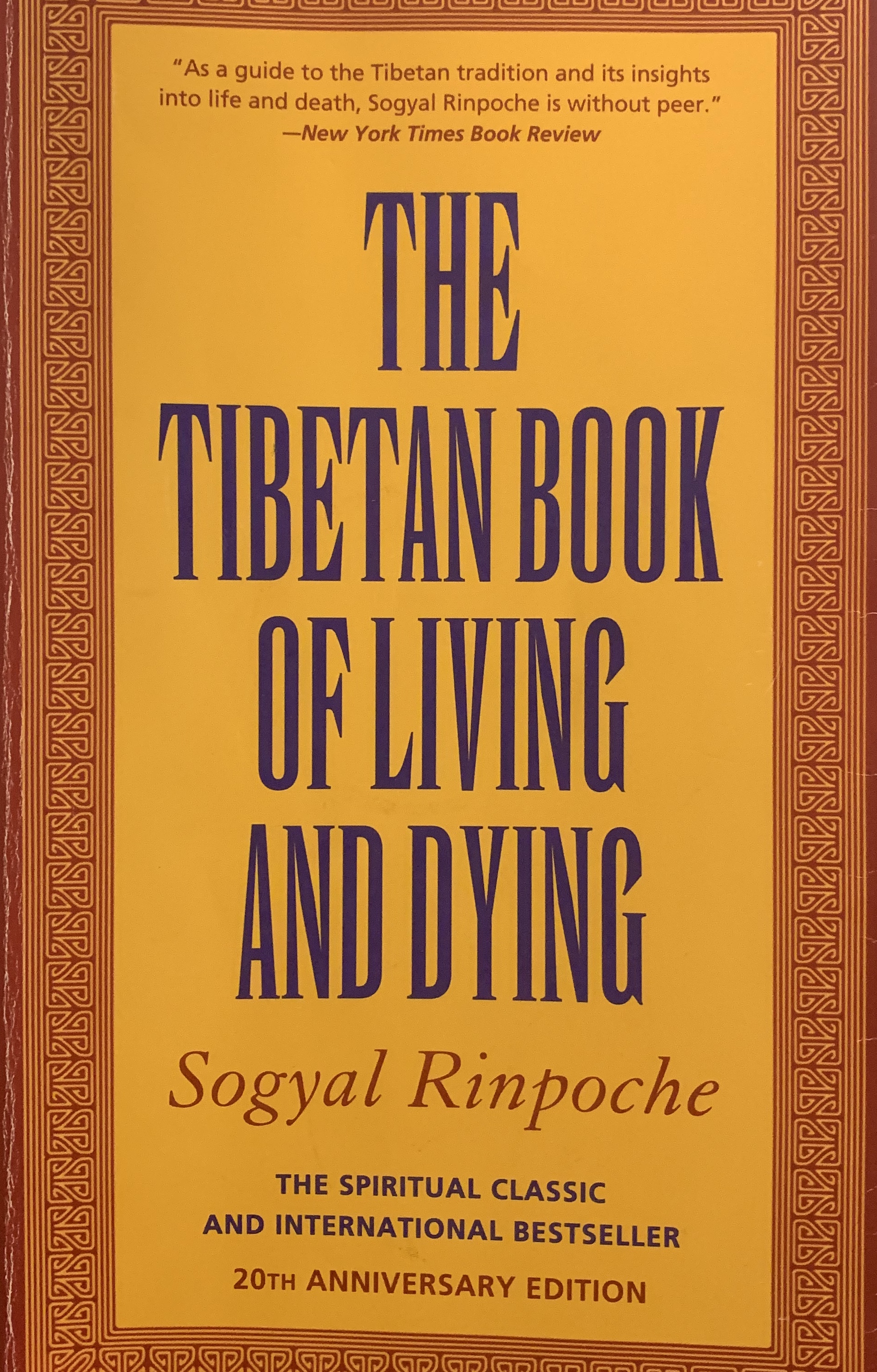

Since reading The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying several years ago, a book I’ve come back to several times, I’ve learned death need not be frightening—even though the dying part can be a little unsettling. Both are things, I think, that must be faced.

It seems to me we should face our own impermanence with as much compassion for ourselves as we do for others. We need not confront our mortality with icy detachment, but with the hope of developing a sense of equanimity about it just as we hope to cultivate in other areas of our lives.

In the past, I’ve tended to believe the admonition of the poet Dylan Thomas:

“Do not go gentle into that good night; Old age should rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

I’m not so sure I buy that any more. If Thomas means we should live as deliberately and fully as possible until we draw our last breath, I’m on board. But if he means we should turn dying into the metaphorical shaking of our fists, I’m not as certain.

I could be wrong.

Like I said, I’m learning.

Read 0 comments and reply