I have been trying to write a reflective piece on my own journey of privilege and bias for days now, and I keep starting over.

Each example of white privilege I’ve reflected on in my life has opened the door to other similar or related examples…until the scope of the ways privilege has affected my life felt bigger than what I felt I could capture in an essay.

It started, of course, with my first breath.

I was born to educated white parents. Neither my father, nor any significant male figure in my life has faced incarceration during my lifetime. I never wondered when my next meal would come. My parents never had to sit down with me and have a conversation about how to survive a confrontation with law enforcement.

I grew up in Ginter Park, a neighborhood within the city limits of Richmond, Virginia. Despite its location, my neighbors were all white—it being one of those cordoned off urban areas that Black families were legally barred from until fair housing became the law just 52 years ago. And even then, Black families were intentionally steered away from that area.

In Richmond Public Schools I stood out and excelled, which I internalized into feelings of great self-satisfaction. I did not consider that many of my peers were food insecure or on assisted lunch programs. I did not consider that many of my peers came from single parent households and did not have parents reading The Chronicles of Narnia to them every evening. I just patted myself on the back for being ahead of the curve.

But it has been as an adult that my benefits from privilege have truly accelerated. I threw away a full academic college scholarship after one tumultuous year and started working as a laborer on a demolition crew.

In six months, at 19, I was the foreman.

Almost everyone in the power structure of construction companies is white. The owners, the project managers, the superintendents. And so, despite throwing away the opportunities of school, I was given more opportunities.

I entered a carpentry apprenticeship program. I worked alongside Black and Hispanic apprentices, but it was suggested to me that I take construction management course work. I worked 50 and 60-hour weeks with night classes in the evenings, and patted myself on the back for how hard I was working to get ahead. I did not consider why I was given those opportunities and my peers were not.

Eighteen years later, I manage multimillion-dollar projects. I sit in a meeting every Tuesday with two owner’s representatives, an architect, and my construction management team. Everyone is white, male, and between 35 and 60 years old. This has been the “rule” for the last 10 years that I have been running work, not the exception.

In the wake of our country’s great upheaval in the name of racial justice and equality, I have been trying to look honestly at what work I have done—what receipts I have for my efforts—and I have become uncomfortable.

On social media, a white friend said that she did not think people should be shamed for their old ways of thinking. But I’m not sure how most of us can look honestly at our relationship with race and not feel a little ashamed. I know I can’t.

What I find most embarrassing is the assurances I gave myself that I was on the correct side of the issue. I took pride in having different politics than most of my colleagues in construction. I took the presence of Black people in my life that I love as indicative of an unbiased heart.

But my actions have often fallen short of the person I imagined myself to be.

I have let racist jokes and comments from coworkers and members of my own family go unchallenged and unaddressed.

When I was sat down by a superior and told that my politics were making it so that people didn’t want to work with me, and that my job might be on the line, I let my voice be silenced.

As media attention has increased surrounding our country’s system of inequality and the brutality of the state, I have written my senator and called my Congress people. But I have never launched a sustained campaign. I have enjoyed the privilege of being able to fall back into complacency. To allow myself not to feel the weight of issues that didn’t impact me.

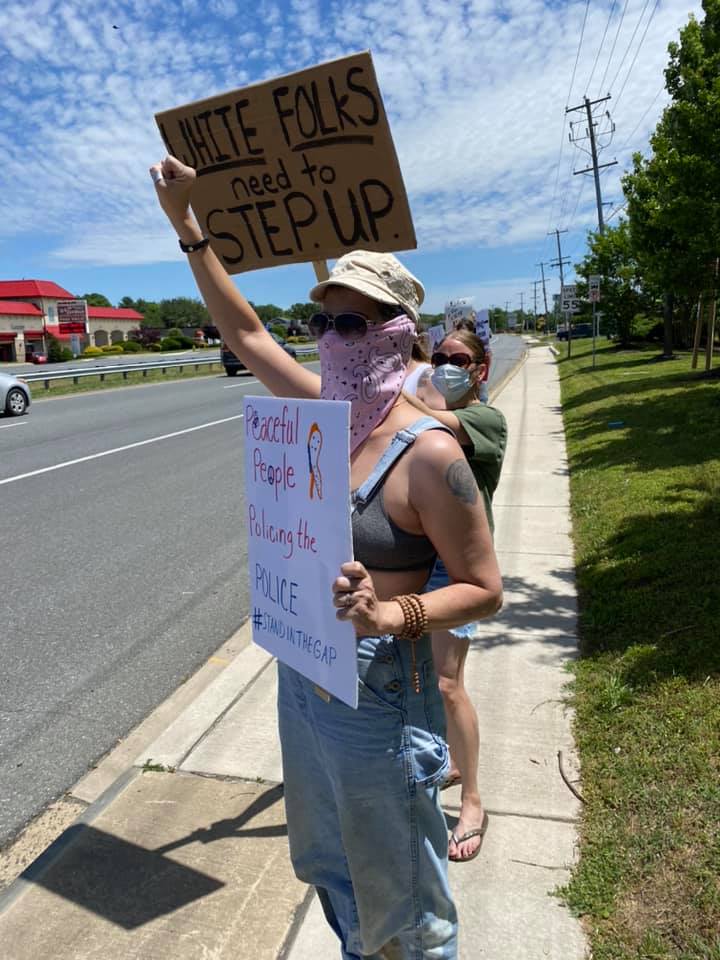

Where I live in rural Maryland, I have allowed myself to be camouflaged among the white faces of my neighbors. Allowing fear of reprisal from them to keep me quiet.

But let’s go deeper. Let’s touch the part that really makes me sick to my stomach. It’s the sneaking suspicion that in some ways I am worse than the “All Lives Matter” folks who shove their middle fingers in my face. Because I cannot claim ignorance. I know the statistics, I’ve read the books, I have seen the trauma on social media of people I care about. I have absolutely no excuse for my poor and inadequate body of work.

There have been times when I have pushed back on social media posts from Black friends. I have felt attacked, afraid of the anger expressed, and hurt to think that they might feel differently about me than they once did. I have come to understand that these reactions were a reflection of my insecurities. I felt that way because I knew in my heart that I have loved them incompletely. Loved them as individuals, while failing to address the systems of inequality that affect their lives—and from which I benefit.

There are no words, no apologies that capture these shortcomings. There is only the mountain of work to be done. Change is a process of pressure and time. Every institution that fails to serve our communities of color needs to feel that pressure reshaping it. Our educational systems, our criminal justice systems, our economic systems.

The work cannot be self-congratulatory, or to signal my virtue, or tied to a hope for reassurance from Black friends.

The work is both the means and the end. It is simply, what I owe.

~

Read 0 comments and reply