When I was first diagnosed with late-stage (chronic) Lyme disease, my doctor told me that the recovery process would be like a dance.

“Sometimes, the infection will take the lead and be in control of your body,” he said, “Other times, the strength of your health will take control.”

Twelve months into treatment, this phrase has held me steady.

Through my temporary remissions and temporary relapses, I have observed the line of equilibrium between the illness in my body and the health of my body bending to and fro. I have been lifted by my health during periods of remission, and I have fallen to my knees at the hands of the disease in times of relapse. The highs and lows of living with this disease are inexplicable to describe to the layperson.

There is both a rhythm and a pattern to Lyme disease.

My symptoms heighten in the days leading up to a full moon. They heighten when I experience insomnia, overexertion, or emotional stress. They heighten at different points in my menstrual cycle. There is a domino effect of how I experience my symptoms—a pattern to how they cascade through my body.

It has taken me a full year to tap into this pattern, this rhythm, and to consciously connect with it. It now provides me with the discernment and grounding I need as I bear witness to the ebb and flow of the disease inside my body.

Before my treatment, I was lost in the perplexing and confusing abyss of migrating, systemic, ever-changing physical symptoms. From hour to hour, day to day, and week to week, my symptoms would differ.

“You have so many different symptoms,” my general physician once told me. “It doesn’t make any sense.”

Lyme disease is an umbrella term for several bacterial, viral, and parasitic co-infections acquired through one tick bite. I have yet to undergo focused treatment for the Lyme infection itself, as my doctor can only tap into treating it once the co-infections have been eradicated.

As I have moved through treatment for Bartonella, Babesiosis, and Viral Tick-Borne Encephalitis (TBE) over this last year, I have learnt a lot about how these Lyme co-infections present themselves in my body. It has been an enlightening process.

Here is what I know now, but didn’t know before:

What Bartonella feels like

In my body, a Bartonella relapse begins with an excruciating internal pulling feeling down the sides of my neck which connects all the way down to my armpits. It’s as if there were a piece of rope running from my neck to my armpit, which someone is pulling on as if I were a puppet. It is physically crippling.

Then, intense anxiety of no emotional origin takes me over, which I can only describe as a constant low-level panic attack. Paraesthesia develops down the inside length of both my arms, from my armpit to my little finger, and my armpits throb in pain. The skin feels as though it is burning and bruised, and it is highly sensitive and painful to touch.

My bladder begins to throb and stab with cystitis, my throat is sore when I wake each morning, I feel sick in my stomach and I am unable to eat, and I become hyper-sensitive to all noise, movement, light, and heat as my brain loses its ability to buffer and adapt to all sensory stimulation and change.

Then comes the bone pain, back pain, rib pain, and sore and sensitive soles of my feet and hands. When I wake, I can hardly roll my body on to its side due to fatigue and pain. I cannot clench my hands to grip anything for they are painfully weak. I develop a tremor in my hands, rendering me unable to lift a fork or spoonful of food into my mouth. I lay in bed in silence and alone in my dark, cool, quiet room until the relapse passes. Usually, it lasts one or two weeks, but prior to beginning treatment for late-stage Lyme disease, I experienced this every day. I was bedbound and immobile on bad days, and housebound and semi-mobile on good days.

What Babesiosis feels like

A relapse of Babesiosis begins with a dull and heavy pressure inside my head. My thoughts and behaviour shift into a dissociative depressive state despite no emotional or psychological provocation.

My thoughts become dark and I am flooded with a compulsive feeling that I am in hell.

When I wake, I cannot distinguish the waking world from a nightmare. I lose my appetite and cannot physically eat. I am flattened and drained with fatigue. My mind plays tricks on me, convincing me that my life and my recovery is helpless, hopeless, and worthless. I feel possessed. I feel evil. My thoughts are not my own; it’s as if my mind has been possessed by an entity. That would be Babesiosis.

I refuse to make decisions, speak to people unless essential, or drive my car during these relapses as I deem myself cognitively impaired, a danger to myself, and not truly “myself.” Usually, it lasts one to two weeks, but prior to beginning treatment, I would experience several consecutive months each year feeling this way.

What Viral Tick-Borne Encephalitis (TBE) feels like

In my body, a Viral Tick-Borne Encephalitis (TBE) relapse begins with a headache and nausea unlike any I’ve ever known, which slowly builds upon itself as each hour passes.

It feels as though a sword has been driven through my brain. I lay down still and cover my head in ice packs. Twisting my neck, raising my head, and movement of any kind sends my head pain sky high. I retch with nausea. Sometimes, I develop meningitis and cannot move my neck. Sometimes, that meningitis leads to hallucinations.

Last year, during an episode, a woman’s voice, as if speaking to me through a Tannoy, coldly and sternly told me, “You cannot escape from this.” It deeply unnerved me and I developed night terrors for months afterward due to this experience.

I only received a diagnosis for my Lyme disease due to extremely fortunate misfortune.

Having had years of severely compromised but semi-functional health, my health rapidly declined in 2018. At the time, I was living in Canada, and my mother had flown out to move me home to the UK as I was barely able to walk and had shrunk to a skeletal weight of six stone due to gastroparesis and dysautonomia. I was severely dehydrated, malnourished, and had adrenal insufficiency.

I was unable to stand or walk without blacking out, and I had begun to have seizures which had led me to hospital several times. The pupil in my right eye no longer constricted when exposed to light, and I remember one of the paramedics in the ambulance acknowledging this as he shone a flashlight in my eye and said to me, “There is definitely something physically wrong with you, but I don’t think you’re going to get your answer here in hospital tonight.”

He was right; I didn’t get my answer in hospital that night.

When my mum arrived in Canada, we packed my belongings up and headed to the airport. We boarded the plane and as I sat there ready for take-off, my body felt paralysed and crippled. My heart was beating irregularly and I felt dizzy despite being sat down. I was feverish and almost vomited. My mum poured water on a tissue and held it on my forehead as she tightly squeezed my hand. I was flooded with a sense that my body was about to die.

The plane was taxiing to the runway to take off and I knew that I needed to get off the plane. I was too paralysed to move and too weak to think; I didn’t know what to do. Then, out of nowhere, a man came running down the aisle to the front of the plane yelling and distressed and fell to his knees on the floor right beside where we were sat. I am, without doubt, sure that this man saved my life. I was too physically sick to survive the flight, had the plane taken off.

At that point, my body buckled in shock and the flight attendant came to assist me. The distressed man was deemed as a potential threat to the flight, and the plane taxied back to the airport: our flight was canceled. A paramedic met me when we re-entered the airport through the gate. He listened to my heartbeat and confirmed that I had an irregular heartbeat, which was not normal for me.

I decided not to go to hospital as I feared that one more stress or change would kill my already weak and crippled body. The month prior, a simple blood draw had sent my body into vasogenic shock—a medical emergency for which I was administered IV fluid in order to increase the volume of my blood. As the needle had begun to draw the blood my vision had blurred and I became aware that my neck could no longer support my head. As my head bobbed downward I began to retch and vomit, breaking out in a profuse fever that soaked my clothes and the chair I was sat on in the doctor’s office.

My blood pressure dropped to a level so low that it was unreadable on the blood pressure monitor. It took my body 45 minutes to recover from this vasogenic shock.

I deteriorated over the following hours at the airport, however, ending up in hospital anyway. I was advised to follow up with my doctor and to ask to be fitted with a Holter monitor to monitor my heart over a 48-hour period, as the ECG at the hospital showed no irregular heartbeat despite the paramedic having confirmed this just hours before. Again, I received no answers in hospital that night.

I was physically unable to fly, and really had no choice other than to seek specialist medical help. A clinic in California had been suggested to me many years prior, which specialised in diagnosing and treating complex chronic illness. And so my mother and I boarded the Amtrak train from Vancouver to San Francisco, where I lay lifeless and grey in the sleeper cabin until we arrived the next morning.

That’s when I received the diagnosis of late-stage Lyme disease and began to understand the severity of the disease.

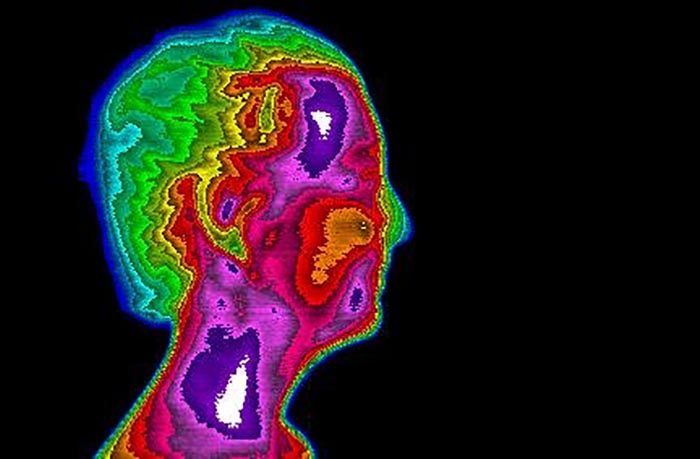

I had various laboratory tests and imaging, all of which showed significant abnormalities in my health. My blood was not clotting properly, thermographic imaging showed my brain was inflamed, and one of my blood tests for infection came back as “abnormal,” due to being so far out of range that it could not be deemed as merely “high.” Others showed high levels of active infection, both bacterial and viral.

I was, on all counts, abnormally ill. Yet, this is exactly what late-stage Lyme disease is: abnormal levels of chronic complex multi-system infection.

I met countless patients at the clinic who were in the same situation as I was, and my eyes opened to all the people I was surrounded by who had also fallen through the cracks of the conventional medical system. They were experiencing relentless, ferocious, complex illness just as I was, and they had ended up here too, having exhausted all other medical options and with nowhere else to go.

For the first time, I no longer felt alone.

For the first time, I no longer felt ashamed of who and what I had become at the hands of this disease. For once, I understood how brave I was to have withstood such severe illness and to have survived it.

The other patients and I would sit there in a room, hooked up to our IV medicine, sharing our stories and kindness to one another. Some were so ill that they were barely able to speak or talk, and some were many years down the road of recovery and remission.

Despite living a wholesome and adventurous life, I had never been so far out of my depth before the period of time between my last month in Vancouver and arriving for treatment in California. Still to this day, I am processing the journey that late-stage Lyme disease has taken and continues to take me on.

It has been wild, it has been rocky, and it has been inescapable: the only way out has been through. I grieve daily, and I have consciously created a home for myself which is safe and quiet. I have lost friends and I have gained them. I have been judged and ridiculed, and I have been accepted and supported.

My mind often takes me back to the traumatic moments of the last few years when I am in remission, and my body relives the harrowing physical experiences when I relapse. My recovery on the physical, emotional, and spiritual level is a work in progress. I have developed strong discernment and belief. I strive to live with as much grace and compassion for myself and others facing affliction, suffering, and isolation. I prioritise my treatment, self-care, nutrition, sleep, mental health, emotional nourishment, and—above all else—my safety and joy.

I seek pleasure, enjoyment, peace, laughter, and humour daily. I am making friends with my upside-down life.

Late-stage Lyme disease is serious and complex. It can cause significant infection and inflammation including, but certainly not limited to, the brain, nervous system, heart, skin, gastrointestinal tract, and the bladder. The disease can impair, restrict, disable, and kill. It can cause a cascade of secondary symptoms, syndromes, and disorders.

There is currently no agreed-upon or approved treatment guideline for Late-stage Lyme disease. It is relentlessly undiagnosed, misdiagnosed, and improperly treated, globally. It is an epidemic that no one is talking about, and it does not receive the medical recognition, research, funding, and support that it warrants.

I urge each and every person reading this to educate themselves on the signs and symptoms of acute Lyme disease, on what to do if bitten by a tick, and on late-stage Lyme disease.

You might just end up saving someone’s life.

If you know someone with untreated late-stage Lyme disease, please offer to fundraise money on their behalf in order to allow them to access the essential medical or holistic treatment that they require. Be kind, respectful, and gentle to them, even in the face of your non-understanding or misunderstanding of their medical condition.

Recognise that your non-understanding and misunderstanding of their disease is a privilege that you have, which those afflicted by the disease do not have, and cannot afford.

To all those dancing with late-stage Lyme disease, you are the stars in the sky, and you are the light in the darkness. You are hope. Relentlessly seek the help and treatment you need, and dance yourselves into remission, my friends.

And when the relapses hit, root yourself deeply into the ground of who you are, remembering that you are not your illness. There is a big, beautiful life out there that is yours to live, and you are brave, committed, and tenacious enough to live it.

Lastly, to all the doctors and health practitioners recognising late-stage Lyme disease and supporting the patients afflicted with it, whether through medical treatment or holistic therapies, there are no words to describe my respect for and appreciation and admiration of you. You are the foundation and the core of treating, supporting, and caring for those with this disease.

Thank you for seeing us, hearing us, validating us, and acknowledging us. Thank you for increasing the quality of our health and our lives. Thank you for helping our bodies heal.

Read 6 comments and reply