Dear Dad,

The other day I was looking for a particular dessert recipe when a cornflower blue, three by five card (grease-stained and slightly dog-eared) fell out of the pile I keep in the drawer in my kitchen.

I smiled when I saw it. I set it down on the counter and scanned the list of ingredients and instructions for “flank steak strips in mushroom sauce.” In all the years you made it, I’m afraid I seriously underestimated how much effort you put into creating your signature main dish, best served with “white rice and a salad” or “fresh green beans”—as Mom wrote in her distinctive (part cursive, part printed) scrawl a lifetime ago.

Reading through the steps took me back 50 years when you started making the flank steak recipe for company, or, sometimes, just because you were in the mood for a fancy meal.

I’m sure I was a middle schooler the first time I tasted it—the hickory-tinged meat, a riot of flavor inside my mouth, out on the cement patio behind our officers’ quarters house in Puerto Rico. When I was in high school, I’d watch you hoist a bag of charcoal briquettes and a bottle of Kingsford lighter fluid and head outside, asking Mom to turn on the reel-to-reel tape of Frank Sinatra hits.

“Night And Day” and “The Girl From Ipanema” wafted from the living room to the backyard where you stood sentry, monitoring the progress of the sizzling beef. Sometimes, you danced, spatula and tongs in hand, when “Fly Me To The Moon” came on. It was one of your favorites. It reminded you of Mom, but she was at the sink peeling carrots to go with the iceberg. So you swayed in the grass without her, the song’s lyrics filling your head, expanding the space inside your chest.

…Fly me to the moon

And let me play among the stars

Let me see what spring is like

On Jupiter and Mars…

A flank steak dinner could mean different things: a good day at the office or the beginning of a long-awaited weekend. It compelled our family of five to gather around the table on sultry summer evenings. Mom, a cigarette between her fingers, would call, “How’s the meat coming?” through the window screen, and you’d give her the signal, three, five, or eight minutes until “go” time.

She’d plug in the electric knife, smoke from her Salem’s mingling with the appetite-whetting aroma of the just-plated beef. You’d slice the steak diagonally, across the grain…whirr, whirr, whirr. That part was important.

Then came the salad and the rice. After the prayer, between bites, we laughed and goofed around. You gave me and my sisters each a funny nickname. Mine was “Flora Flapjaw,” because I talked so much.

Those were the halcyon days, filled with optimism, conviviality, and excitement for the future. You got out of the Navy, went back to college, and earned a master’s degree. We moved from California to Oregon, and you landed a job in construction management. You bought a new Buick Le Sabre and entire rooms of Ranch Oak. You paid for three university educations and three weddings and had money left on the side. I internalized your work ethic and admired your success. I hoped you were happy.

When I was a teenager still living at home, you had three inviolable rules: no wearing hot pants out of the house (too suggestive), no watching “Dark Shadows” on TV (too weird), and no disrespecting our mother (just plain wrong). You didn’t give Mom nickname. Her name was always “Beloved.”

…Fill my heart with song

And let me sing for ever more

You are all I long for

All I worship and adore…

The recipe on the blue card was a bit complicated. It wasn’t something you could just whip up when Dan Rather was on (you had to think of it ahead of time). The meat needed to marinate in the fridge, in sauterne, for at least two hours, preferably overnight. When I made it later on, for my own family, I’d skip the part where you were supposed to “have your meatman remove the thin surface membrane from the steak.”

I never asked that of my meatman—I never even had one. I took the membrane off myself, and not being someone who enjoys cooking all that much, I felt accomplished. Mom had added a helpful corollary that says, “You can do it!” in small print. Her encouragement is with me still, from beyond, from here to eternity.

As is yours, Dad. You’ve taught me so much about living precisely because you’ve lived through so much. The Great Depression, polio, The New Deal, Korea, the moon landing, Vietnam, Watergate, AIDS, the end of the Cold War, the rise of the Internet, September 11, The Great Recession, Mom’s long goodbye and passing, and COVID-19.

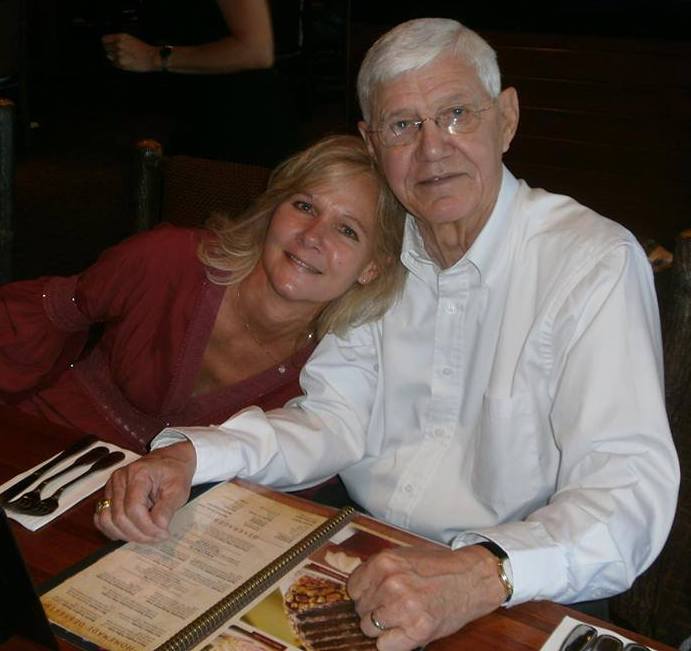

I’ve had the privilege of watching you and learning from your example for 62 years out of your 90 years. You are a study in dichotomies, at once a small-town Iowa boy, and a big deal flight squadron commander—a person of deeply held convictions, but also abundant grace and generosity.

You’re a doting father, grandfather, a great-grandfather, and the man who saved my life several times: first when I was 15 and afflicted with debilitating insomnia, and more recently, when I suffer from anxiety and sleeplessness. “Don’t worry, Nance,” you told me in 1973, sitting at the foot of my bed, trying to quiet my quaking heart. Your voice was calm and reassuring. You were right there with me. “Things will look better in the morning,” you said, and they did.

I still recall those words and repeat them to myself as needed.

Now your world is smaller—most often me, my sisters, and our husbands. Sometimes, one of your grandchildren stops by to have coffee or perform a task that needs doing: gutter cleaning, deck staining, or moving something into or out of your house. You make quick visits to see your great-grandson sitting up, babbling, playing with his toys, flashing a big two-tooth smile your way. Coronavirus keeps you masked up and shut down. You want a hug, but you can’t get one—not a long one, anyway—so your little dog curls up in your lap, offering warmth.

It’s a full-circle feeling, this singular special day, the portal to your 10th decade on Earth. You always say you don’t want to live to be 100. You’re tired, and you miss the wife to whom you were devoted for nearly 60 years in life, and now seven years in death. You go to the cemetery and place flowers on her grave a couple of times a month, but it is hardly the same. You call her name in your dreams and hope for a sweet reunion beyond the veil. She is there in the mists, waiting for you, reaching for you, making music for you. I know it.

…In other words, please be true

In other words, I love you…

Thank you for loving me, no matter what, and for caring for Mom so well. I’m fortunate to be your daughter. You have given me so much. You’ve always been in my corner. As long as I live, I will want you here with me. Please keep breathing into your soul the unconditional truth that I love you and always will.

Writer Anne Lamott says, “Help me, help me, help me.” It is her morning petition. “Thank you, thank you, thank you” is her evening meditation. They are mine as well. You have helped me, Dad, and I am thankful for that.

On this day, and every day to come, you are my hero. Happy birthday.

Love,

Nancy. (aka Flora Flapjaw)

~

Read 0 comments and reply