I want to tell you a story about the mystic poet and artist, William Blake, and about my yoga teacher Mark Whitwell, and how they came to meet. You could say I introduced them. You could even say that William Blake is my guru, but it only through the yoga – the heart of yoga – that I learned with Mark Whitwell that I was able to

There is some mysterious power in Blake’s communications that drew me in, something that travels through time and space from 1790s London and arrives in our hearts here and now. His visions are woven into our culture — Huxley’s ‘Doors of Perception’ come from Blake, which in turn gave us ‘The Doors,’ and he has inspired so many — Patti Smith, Phillip Pullman, Angela Carter, Alan Ginsberg, Yeats, Yanagi Soetsu, Bernard Leach, the list goes on. You might have come across some of his incredible lines, like these, ‘Auguries of Innocence’:

A robin redbreast in a cage

Puts all heaven in a rage.

A dove-house fill’d with doves and pigeons

Shudders hell thro’ all its regions.

A dog starv’d at his master’s gate

Predicts the ruin of the state.

A horse misused upon the road

Calls to heaven for human blood.

Each outcry of the hunted hare

A fibre from the brain does tear.

A skylark wounded in the wing,

A cherubim does cease to sing.

The game-cock clipt and arm’d for fight

Does the rising sun affright.

Every wolf’s and lion’s howl

Raises from hell a human soul.

What a voice for ahimsa (non-harming) and wildness to come of industrially revolting England, referred to by Blake as the ‘Satanic mills.’ Right there in the middle of London, an obscure printmaker living in poverty, surrounded by abuse of every kind, at the centre of the vicious machine of empire, and putting down his vision of respect for all life, for us in the future to read and weep over. In his own time he was seen as insane. He had a few patrons who recognised his talent, if not his validity. Rejected his entire life, struggling in poverty to produce his self-published books, he lay on his deathbed in his 60s, told his wife Catherine that she had forever been an angel to him, sketched a final picture of her, and then sang joyful hymns until he passed on. What are we to do with such a figure?

What I found was that through the university system within which I met and engaged with him, I was accidentally and invisibly forced into a position of being a consumer of Blake, a consumer of inspiration. I would read one of his poems, feel something, and then the feeling would wear off and I’d be forced to go looking for it again, go looking for some kind of an inspiring hit. This is why we stick quotes on magnets on our fridge! I was only able to relate to Blake as an external source of inspiration, as something to comsume, however pleasureable. And yet I don’t believe that is what he would have wanted, what a Rumi or a Rabia would have wanted for their readers. On Blake’s headstone his words are engraved:

I give you the end of a golden string

Only wind it into a ball

It will lead you in at Heaven’s gate

Built in Jerusalem’s wall

These words and his entire writings demand some kind of an active process from the reader. Some kind of journey, some kind of engagement more than marvelling and admiring, like a museum piece. And more too, I am suggesting, than just being inspired.

What we need is a way of actualizing our inspiration, and including ourselves in the process. So we’re not stuck in a consumer relationship with things that inspire us. Because something has happened to us: the dominant culture has desensitized us by an assault on our senses. We can only feel these moments of expansion in very little blips, perhaps standing on the top of a mountain, or sitting in the Himalayas, or looking into the eye of a whale, or when all the conditions come together perfectly on a sailing boat, or maybe making love or at a certain moment when you read a certain line and your heart responds. We’re left with trying to chase those moments and feel them again. And the stress of trying to chase these moments actually further desensitizes us to that feeling being available everywhere, all the time.

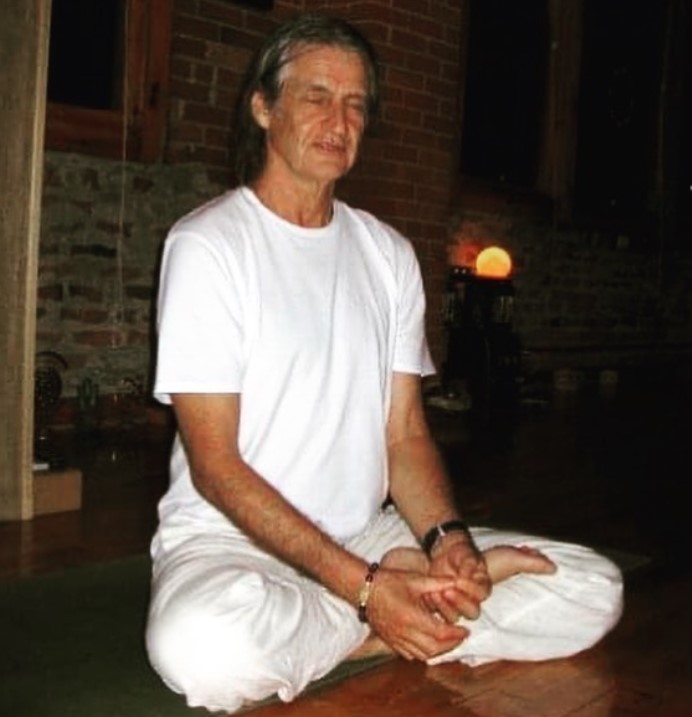

My teacher Mark Whitwell passed on beautiful quote from the yoga tradition: that “Yoga is what you do to actualize what inspires you.” So it doesn’t matter if you’re inspired by poetry, like I have been, or whether you’re inspired by natural wildlife, or inspired by a relationship with a very special person: we need a way to respond to that inspiration, otherwise we’re stuck in a disempowered role needing to consume that thing over and over again.

This model of the consumer leaves us in a very disempowered place, where we think that when we get a feeling, it’s coming to us from the outside. For example, when I was reading those poems, it really seemed to me like the poem was doing something to me, like it was giving me something. There was an invisible framework occurring around these experiences, which was the unconscious belief that I was not a mystic. I was not a special person. I was some kind of scabby loser academic, whereas this Blake person writing the poem was really amazing. This is what we could call the social dynamic of disempowerment. As long as I’m stuck within that interpretation of my feeling of inspiration, then I’m trapped, always having to go and get it from other sources. Whether that’s just buying stuff, literal consumerism, or consuming experiences, or consuming other people with a constant demand on them to give us what we want.

What I have found is that the function of the yoga in relation to our inspiration is to help us resensitize the system, and then we can start to feel, “Oh, wait a minute, that was ME responding to those things.” When I read that poem, that was my heart that felt something. How did I even know that those words were powerful and true? I’m reading a cereal packet, I’m reading a shampoo bottle, and then I read a poem. What is it in me that knows that the poem has power that the shampoo bottle doesn’t have? There is obviously something in me recognizing that truth, there must be something in me that knows that it’s true already. And that resonates with it.

This is a hugely empowering position: that whenever something has happened in your life that inspires you— whether it was swimming with manta rays, or looking at an incredibly beautiful view—that feeling of being at one with your surroundings was coming from your own system. It wasn’t some experience that was added on to you like an extra bauble on an already-burdened Christmas tree. No, the clouds broke open for a moment, the sun shone past our usual disempowered frameworks. For a moment, you could feel how we are actually part of nature and how we are actually part of that flow. But then our usual mental structures put in us by society close over again. That connection is still there, the sun behind the clouds, but we’re not experiencing it any more.

What I learned from my teacher Mark Whitwell is to think of yoga as a garbage removal process for those dysfunctional outdated social ideas that have been put in us. We’re not seeking to consume any kind of extra inspiration. Because most of us have already been gifted with these moments. Now we just need a way to actualize them in our lives, we need a way to respond.

I think of all the many young people trotting around India looking for incredible experiences, and most people will find their incredible experience in some form. The question is, what do they do when they go back to their own home country? How do you respond to that glimpse of power and beauty that you’ve had, or if you go out into the wilderness, and you have a transformative experience, or you take some kind of psychedelic, and you have a transformative experience, what happens next? It is what happens next that determines if we’re stuck as a consumer, or if we’re able to make that step into an empowered relationship with inspiration.

When I say that Yoga is what can bridge this gap, it’s not so much the actual physical movements and the shape of them that matter when we’re doing our practice, it’s the mood. The most powerful thing to do is when you do your actual yoga asana, practice your breathing and moving, think of that thing that inspired you — the person or the view or the moment or whatever it was. Think of your practice as participating in the feeling of that moment. That moment was not just a come-and-go experience. That moment was something real, something true. And it came from you. It was you recognizing that power of that moment, it wasn’t any external circumstance doing it to you, it was you responding. This is what gets us out of that consumer relationship.

So we don’t have to keep buying spiritual books. And we don’t have to keep searching for those particular experiences. Not to say that we don’t do them— I’m definitely not suggesting that we stop reading poetry. But once we know that the recognition was our own, something we can participate in any time we want, then we’re free to do it for pleasure.

And this is crucial, because if you keep going back and back to a source of inspiration, trying to get the feeling from it, it wears off after a while. We develop a tolerance. At first, it’s really powerful—you read it, or you do it, you get really high, it’s amazing! Then you start doing it every day, because it was so good. And then it stops working so well. So you have to move on to the stronger thing to get that feeling. The problem with that is, the more you escalate the strength of the inspirational high, the more you get desensitized and less able to feel that now, every day, the sublimity of day to day moments, which is what we really need to do to turn culture around.

Everyone can think of something in your life that’s inspired you: giving birth is an incredibly powerful one which people who have done that have. There’s no need to recreate that moment, all we need to do is know that it was true, and that that wasn’t an additional or merely external experience. It wasn’t a possession. It was a moment of loss, of seeing things how they actually are. Reality broke through. And yoga is simply a more steady, self-empowered, reliable way of kind of clearing the lens, that doesn’t require us to trek up a mountain or keep having children. Some call it “cleaning the pot,” enabling to see things as they are more often. Blake called these “the doors of perception.” This is at the root of his ethic of reverence, his statement that “Everything that lives is holy,” because the more clearly we see things as alive, connected, autonomous, then the more we treat them with respect. An ethic of care is a very natural flow-on effect of seeing more clearly. Your yoga is here to use as a response to inspiration. That has always been one of the things that it is designed to do.

About the author: Rosalind Atkinson is a Yoga teacher and researcher, a writer, a classical pianist, printmaker, illustrator and founder of publishing house @silversnakepress. She lives in Fiji and Aotearoa New Zealand with her partner and teacher, Mark Whitwell.

Read 0 comments and reply