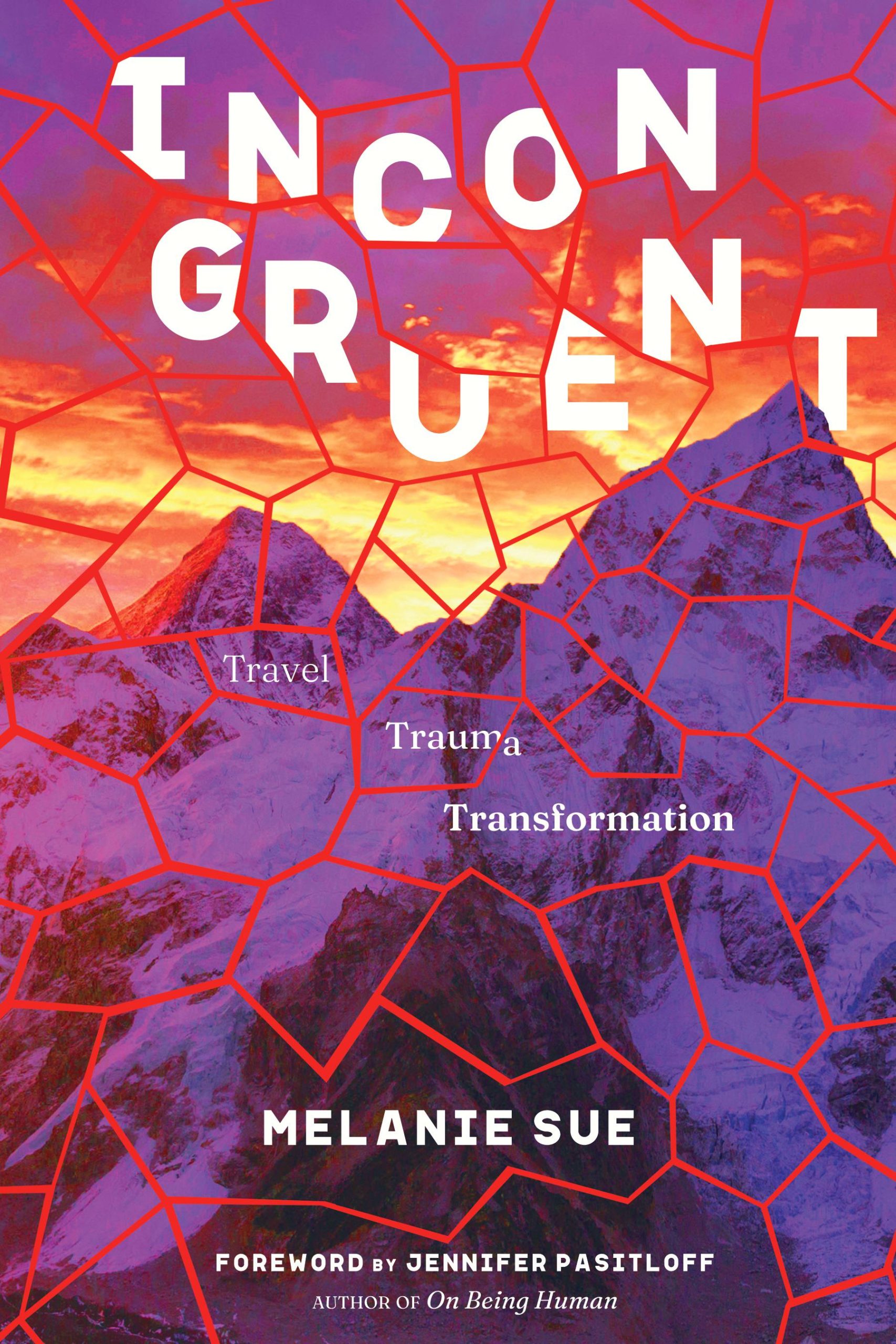

This is an excerpt from Incongruent: Travel, Trauma, Transformation by Melanie Sue Hicks.

~

Blue Butterflies

“Just concentrate on the blue butterfly.” My mother’s words echo in my mind each time I stepped onstage to sing.

Our church had a large circular stained-glass window with four distinct quadrants. The only one I recall was the top left which held a large blue butterfly. It would sparkle in the morning sunlight, and I could project the fluttering of my nervous energy onto the fluttering of those sparkling wings.

Although no American Idol star, in this small-town church, I held my place as a regular soloist. Sunday morning hymns, valentine fundraisers, holiday and summer musical extravaganzas, and Sunday night youth bonding over acoustic guitars. Music was the lens through which I could understand the world. And in that little church, it is the lens through which I could understand God.

My connection to spirituality runs deep. It’s the core of how I choose to live my life. But it doesn’t look like any single traditional religious teaching. I haven’t stepped inside a church outside of a holiday in nearly two decades. I am viscerally opposed to the trappings of pageantry associated with services and the hypocrisy that rages when religion is used to push political agendas.

I grew up in a progressive, loving, and highly welcoming church, sheltered from the negative aspects of religion, spared of harsh judgement and hypocrisy. It was a place I felt love, acceptance, and encouragement. It was also a place of relevance and inspiration.

Dr. Herb Sadler was a scholar of great literature as well as a religious devotee. His sermons would perfectly interlace classic themes of great modern writers with biblical lessons and then seamlessly overlay them into the news and world events of the day. Perhaps the only man I have ever known who could intuitively know what weighed heavy on his parishioners’ hearts and offer them both a biblical lens as well as inspiration from other great historians and documentarians of the world. Through these illustrations, I grew to interpret both God and my own soul.

It was not until I left for college that the bubble of religious graciousness was abruptly burst. As a freshman in college, I found a small but modern church on the edge of campus and began to attend Sunday services. The look of the sanctuary and the feel of the pews was the same, but it held none of the loving energy I was accustomed to. As the weeks drew on, I felt more and more disillusioned. In this minister, I heard no words of modern literary wisdom or acknowledgement of the state of the world. In fact, there was little connection to the modern world at all. What good are these learnings if I cannot parlay them into my everyday life? The disenchantment grew only stronger as I arrived week after week, alone, nearly ghostlike in my anonymity. There were no friendly faces to welcome me, no friends to be made. It was just me in a nondescript pew, halfway back in the sanctuary, singing hymns and desperately grasping for spiritual connection that lit my heart on fire.

As I traveled the world, I studied and appreciated the best and worst of religious traditions. Religion can be beautiful as a source of strength, healing, and connection. But it can also be incredibly ugly. People are shamed, wars are waged, lives are ruined, all in the name of religion. And it enrages me.

If what we know about Jesus is true, he was undoubtably the prophet who taught us more about love than perhaps any other human being in history. He consistently ignored or even denied exclusionary or punitive texts in his own Jewish Bible in favor of passages that emphasized inclusion, mercy, and honesty. As he traversed a tumultuous world, he stopped to really see people and make them feel valued for who they were. He loved the unwanted as fiercely as he loved the prominent. Perhaps this is why I am so deeply offended by the bastardization of that love by those who spew only hate in the name of so-called Christian faith. In particular, the wave of politicians who have taken up discrimination and the restriction of human rights based on completely false doctrine.

Over my life, I have become more resolute about my own version of spirituality. I believe the best way to honor my Christian upbringing is to love people for who they are, not stereotypes we hold of people “like them.” I believe it is everyone’s right to hold themselves to whatever values and standards they wish, but it is not our right to force those standards on others. Who are you to throw stones? In fact, the more shade people throw at others, the more ferociously I want to stand and defend them.

As a deeply intuitive human, I can instantaneously sense a person’s humanity. And to me this is the absolute most important aspect of human connection. I do not care who you love, what color your skin is, who you worship, what you do for a living, or what mistakes you might have made in your life. I simply cannot comprehend why any of that matters in the slightest.

In contrast, I am fiercely in love with the best in the human spirit. With the depths of our heart and our intentions. I care whether or not you have empathy for your fellow human. I care whether or not you make daily decisions based in kindness, love, and acceptance. I care about selflessness and humility in a world where narcissism and greed are prominent.

Calling Uncle

After less than a year, I left that little church outside campus and never went back. Anywhere. For the next decade, my presence in a church was an occasional obligatory holiday with the family or a friend’s wedding. During this time, I searched and found meaning in the study of other religious traditions, in meditation and yoga, and in the very rare silent prayers to a God who felt a million miles away. But something in my soul ached for more.

And then one day, in my late-thirties under a cloud of depression, I sat on the floor and called uncle on the silent treatment I was giving God. And I was welcomed back with open arms. Far from perfect, my goal each morning became honoring that blue butterfly, my own visual representation of God, by loving others through my time, talents, and treasures. And my goal each night is to give grace for my imperfections and gratitude for the chance to be alive. I do not believe my strength is the articulation of faith, but rather the embodiment. For me I choose action over words.

Big Brown Eyes

My hands were blistered beneath the heavy leather work gloves, and my contacts were stinging from the sweat dripped suntan lotion running into them. My back ached, and my biceps were shaking. I had been standing in the same spot for nearly five hours, cutting rebar and bending small metal pieces to fasten around it. We were a small but mighty team of eighteen, trading our Thanksgiving turkey and football for eight days in the blazing sun of rural Nicaragua building houses with Habitat for Humanity International.

In this country, there is no heavy machinery or prefabricated materials. Everything must be done by hand. Each morning, we mixed concrete and mortar in small pits we dug in the earth. To my surprise, only one ingredient separates the two when making them from scratch. We kept the mixtures wet by periodically hauling and dumping buckets of water on them. We made an assembly line to move more than one hundred concrete blocks from the delivery pile to the job site thirty yards away. We stamped concrete floors, built block walls, and as illustrated above, cut rebar—lots and lots of rebar. We had only a set of hand wire cutters to cut the eight-foot sections and plyers to bend the small metal pieces around the bundles of three. After ten bundles were assembled, we called to another team to retrieve and deliver them to the house approximately twenty yards away. It was painstakingly slow and yet, it was extraordinary.

By week’s end, we were sore, sunburned, exhausted, and transformed. We had used our physical time and treasures to change the life of one family forever. It may have been only one family, but you only had to look into the big brown eyes of a little girl who was to live in that house to know it was worth every ounce of effort. In the eyes of this little girl, who had been sleeping on the floor in a small room with seven family members her entire life, you could see hope. Hope for a better life. Hope for a more comfortable place to learn, to grow, and to thrive. This to me is the best I can ever do for humanity. Service is my religion.

Over the years, I have said yes as often as possible to moments like this one. From urban farming in some of the most economically depressed parts of Baltimore to landscape planting in the cheerful view of animals at the Tampa Zoo. From building handicap ramps for the elderly in Jacksonville to building bunk beds in a Refuge house for domestic violence and sex traffic survivors in Atlanta. From childhood literacy efforts around Florida to food distribution in Colorado. When asked, there is no place I will not travel or initiative with which I will not participate. It is both a selfless and selfish simultaneously. It is my way of giving back to humanity and of repenting for the harm I might inadvertently do on any given day.

“The good you do today may be forgotten tomorrow. Do good anyway.” ~ Mother Teresa

We sit at the High Camp for over an hour, feeling the quiet energy of the hopes, promises, and sorrows that accompanied other’s visits. It is difficult for me to stay still, physically and metaphorically. But every day I make the attempt. On this day, I close my eyes and go inside. The sound of the wind swirling mirrors the stirs in my own soul. It whistles in my ears and blows my hair onto my face. The chilled air burns my throat when I breathe in deeply. The rock I am perched upon is cold, hard, and awkwardly shaped. I implore myself to continue to sit. To feel it all. To remind myself I will likely never be back in this place again and I will certainly never again have this moment in time.

Few people really partake in the benefits of meditation. There is a deep fear that keeps us away. It is illustrated in our natural frenetic tendency to fill gaps in conversation with useless chatter or the squirming we do in our seats when a group speaker allows uncomfortable silence. We are viscerally afraid of the still, of the silence. Belonging expert Crystal Whiteaker calls this the shadow work. It is scary, but it must be done. But exactly what is it about shadow work that scares us?

To really be still means to sit with our whole selves. It means laying down the crutch of busyness. It means putting aside our sense of self- importance. It means coming out from the shadow of self-sacrifice for family or others. It is just stillness. Sitting naked in your own soul is a dark and scary place for many of us. But there is simply no other way to truly know yourself, deeply, authentically know who you are. And without knowing who you are, you will never really know what you are capable of and never truly find joy.

“Only when we are brave enough to explore the darkness will we discover the infinite power of our light.” ~ Brené Brown

~

Please consider Boosting our authors’ articles in their first week to help them win Elephant’s Ecosystem so they can get paid and write more.

Read 0 comments and reply