From the beginning of human evolution on this planet, people have tried their best to be happy and enjoy life.

During this time, people have developed an incredible number of different methods in pursuit of these goals.

Among these methods we find different interests, different jobs, different technologies and different religions. From the manufacture of the tiniest piece of candy to the most sophisticated spaceship, the underlying motivation is to find happiness.

People don’t do these things for nothing. During the course of human history; beneath it all is the constant pursuit of happiness.

However—and Buddhist philosophy is extremely clear on this—no matter how much progress we make in material development, we’ll never find lasting happiness and satisfaction; it’s impossible.

Lord Buddha stated this quite categorically. It’s impossible to find happiness and satisfaction through material means alone.

When Lord Buddha made this statement, he wasn’t just putting out some kind of theory as an intellectual skeptic. He had learned this through his own experience. He tried it all: “Maybe this will make me happy; maybe that will make me happy; maybe this other thing will make me happy.”

He tried it all, came to a conclusion and then outlined his philosophy. None of the Buddha’s teachings are dry, intellectual theories.

Of course, we know that modern technological advances can solve physical problems, like broken bones and bodily pain. Lord Buddha would never say these methods are ridiculous, that we don’t need doctors or medicine. He was never extreme in that way.

However, any sensation that we feel, painful or pleasurable, is extremely transitory.

We know this through our own experience; it’s not just theory. We’ve been experiencing the ups and downs of physical existence ever since we were born. Sometimes we’re weak; sometimes we’re strong. It always changes.

But while modern medicine can definitely help alleviate physical ailments, it will never be able to cure the dissatisfied, undisciplined mind. No medicine known can bring satisfaction.

Physical matter is impermanent in nature. It’s transitory; it never lasts. Therefore, trying to feed desire and satisfy the dissatisfied mind with something that’s constantly changing is hopeless, impossible. There’s no way to satisfy the uncontrolled, undisciplined mind through material means.

In order to find satisfaction, we need meditation.

Meditation is the right medicine for the uncontrolled, undisciplined mind.

Meditation is the way to perfect satisfaction.

The uncontrolled mind is by nature sick; dissatisfaction is a form of mental illness. What’s the right antidote to that? It’s knowledge-wisdom; understanding the nature of psychological phenomena; knowing how the internal world functions. Many people understand how machinery operates but they have no idea about the mind; very few people understand how their psychological world works. Knowledge-wisdom is the medicine that brings that understanding.

Every religion promotes the morality of not stealing, not telling lies and so forth.

Fundamentally, most religions try to lead their followers to lasting satisfaction. What is the Buddhist approach to stopping this kind of uncontrolled behavior? Buddhism doesn’t just tell us that engaging in negative actions is bad; Buddhism explains how and why it’s bad for us to do such things. Just telling us something’s bad doesn’t stop us from doing it.

It’s still just an idea. We have to put those ideas into action.

How do we put religious ideas into action?

If there were no method for putting ideas into action, no understanding of how the mind works, we might think, “It’s bad to do these things; I’m a bad person,” but we still wouldn’t be able to control yourself. We wouldn’t be able to stop ourselves from doing negative actions.

We can’t control our mind simply by saying, “I want to control my mind.” That’s impossible. But there is a psychologically effective method for actualizing ideas.

It’s meditation.

The most important thing about religion is not the theory, the good ideas. They don’t bring much change into our life. What we need to know is how to relate those ideas to our life, how to put them into action.

The key to this is knowledge-wisdom.

With knowledge-wisdom, change comes naturally; we don’t have to squeeze, push or pump ourselves.

The undisciplined, uncontrolled mind comes naturally; therefore, so should its antidote, control.

As I said, if we live in an industrialized society, we know how mechanical things operate. But if we try to apply that knowledge to our spiritual practice and make radical changes to our mind and behavior, we’ll get into trouble.

We can’t change our mind as quickly as we can material things.

When we meditate, we make a penetrative investigation into the nature of our own psyche to understand the phenomena of our internal world. By gradually developing our meditation technique, we become more and more familiar with how our mind works, the nature of dissatisfaction and so forth and begin to be able to solve our own problems.

For example, just to keep the house neat and tidy, we need to discipline our actions to a certain extent. Similarly, since the dissatisfied mind is by nature disorderly, we need a certain degree of understanding and discipline to straighten it out.

This is where meditation comes in. It helps us understand our mind and put it in order.

But meditation doesn’t mean just sitting in some corner doing nothing.

There are two types of meditation, analytical and concentrative. The first entails psychological self-observation, the second developing single-pointed concentration.

Perhaps you’re going to say, “Concentration? I don’t have any concentration,” but that’s not true. Without concentration, we couldn’t survive for even a day; we couldn’t even drive a car. Every human mind has at least a superficial degree of concentration.

Perhaps you’re going to say, “Concentration? I don’t have any concentration,” but that’s not true. Without concentration, we couldn’t survive for even a day; we couldn’t even drive a car. Every human mind has at least a superficial degree of concentration.

But developing that to its infinite potential takes meditation—a great deal of meditation.

Therefore, we all have to work on the concentration we already have. Of course, when we lose control of our mind, when we get angry or overwhelmed by some other emotion, we lose the little concentration that we do have. But single-pointed concentration is something that does exist within us.

It is possible to attain—concentration is not beyond reach, way up in the sky with no connection to us. We don’t have to approach concentration from a long way off. It’s not like that. We already have some concentration; it just needs to be developed.

Then we can straighten out our disorderly, dualistic mind. The dualistic mind is not integrated. As long as it remains that way, it remains dissatisfied by nature, and even though we think we are physically and mentally healthy, we’re mentally ill.

We tend to interpret dissatisfaction extremely superficially. We say, glibly, “I’m never satisfied” but we don’t really understand what dissatisfaction is or how deep it runs.

Someone suggests, “You’re dissatisfied because you didn’t get enough milk from your mother,” and we think, “Oh, yes, that’s probably why.”

This kind of explanation of mental problems is totally off the mark; a complete misconception. Also, dissatisfaction does not come from only inborn, internal sources. It can also come from philosophy or doctrine.

Wherever it comes from, dissatisfaction is a deep psychological problem and not necessarily something that we’re consciously aware of. We think we’re healthy, but then why can a small change in your conditions cause us to totally freak out?

It’s because the seed of problems lies deep in our subconscious. We’re not free of problems; we’re just unaware of what’s in our mind. This is a very dangerous situation to be in.

Analytical meditation, checking our own mind, is not something that demands strong faith. We don’t need to believe in anything. Just put it into practice and experience it with our own mind. It is an extremely scientific process.

Lord Buddha taught that it’s possible for all people to reach the same level of view—not materially but internally, in terms of spiritual realization.

Through meditation, we can all attain the same goal by realizing the ultimate nature of our mind.

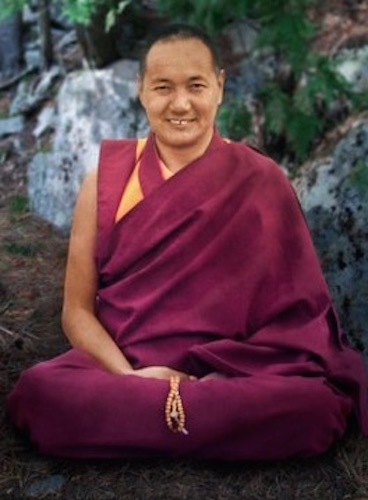

* Read more from Lama Yeshe’s The Peaceful Stillness of the Silent Mind, a series of lectures given in Australia in 1975. Edited by Nicholas Ribush. Freely available from the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive.

~

Love elephant and want to go steady?

Sign up for our (curated) daily and weekly newsletters!

~

~

Author: Lama Thubten Yeshe

Editor: Ashleigh Hitchcock

Share on bsky

Share on bsky

Read 0 comments and reply