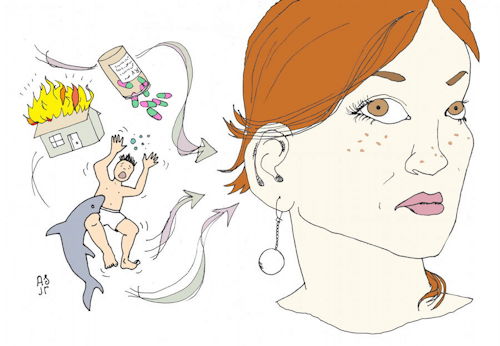

Author’s note: Emmy the Empath is a cartoon character I created in order to explore the strange but too seldom discussed ordeals that empaths share. What’s it like to walk through a crowded world while feeling—intensely, involuntarily, whether we like it or not—the feelings of others? I know. Emmy knows. Perhaps you do, too.

As an empath, Emmy is a magnet for the sad, mad, depressed, desolate and desperate of this world.

They seek her out, describing their torments. Sometimes they tell her why they want to die.

Does this happen to you? Do strangers and acquaintances confide amazingly dark things to you? Then maybe you’re an empath, too.

Some empaths were born empathic. Others weren’t, but became empaths very young, while growing up with troubled people: narcissists, say, or addicts or the mentally ill—with whom all interactions feel like navigating rocky coasts. Endure enough of such ordeals and you’ll become (against your will, as a survival tactic) hypervigilant—and hypersensitive to other people’s moods.

But become hypervigilant and hypersensitive to other people’s moods, and those whose moods torment and scare them seek you out.

That’s because they know—without knowing how they know, or what you are—that you’ll soak up their sorrow, fear and rage as easily as sponges soak up spills.

You might not want to. But they know you will.

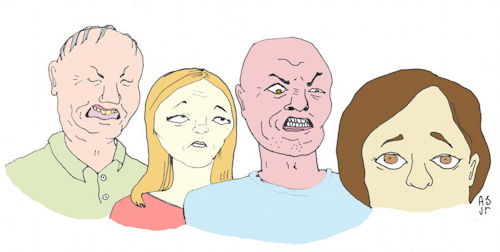

Emmy’s mother was a dignified, well-educated, tasteful graduate of famous universities. She taught Emmy important lessons, such as how to be observant and polite. She also often said, while watching movies on TV or perching on the end of Emmy’s bed: “I wish I was dead.”

Emmy knew this without being told. For as long as she could remember, maybe even in the womb, Emmy had felt self-loathing and sorrow swirling from her mother into herself—into her very cells—like lotion, electricity, sound waves and strong perfume.

Emmy tiptoed through her childhood home, hoping her mother would not hear her, summon her and tell her, while sipping cold coffee, slicing fruit or sitting on the toilet, awful things such as “At funerals, I always wish I could switch places with the corpses.”

Adults and children, even total strangers, often made such inappropriate statements to Emmy: not abusive but intrusive, stranger than a child could understand. It was as if they saw her as a kind of confidante they’d never need to actually befriend, or as a priest hearing confessions, or even something inanimate, such as a wishing well.

One day a girl Emmy had never seen before approached her on the school playground.

“My daddy,” said this girl, making strange gestures, “just died in the war.”

Wherever she went, people told Emmy their troubles.

This is commonplace for empaths.

Emmy’s college friend, Aurora, was athletic and hilarious. She swam, took dazzling photographs and was depressed.

Aurora often threw books and shoes at her dorm-room wall while screaming “I! Will! Kill! Myself!”

Emmy always crouched in a corner pleading “Don’t do it. Don’t do it. You are smart, good and beautiful.”

Eventually, Aurora always stopped throwing things and thanked Emmy.

“You saved me again,” she’d always say—but sometimes this took hours.

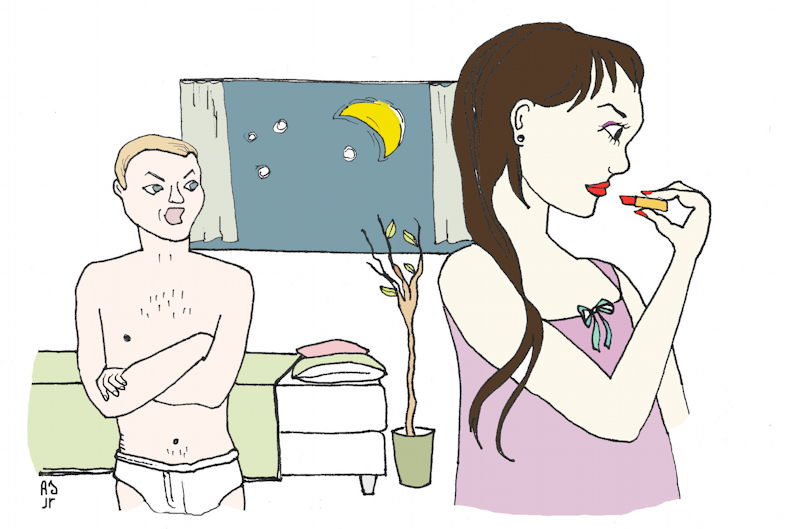

After college, Emmy made another friend: talented, sweet, delicate Kayla, who wrote mysteries that editors rejected. Kayla’s boyfriend, Jared, ordered her to wear full makeup constantly, even to bed. Jared said that, were he president, he would sentence all ugly people to die by firing squad.

Kayla used to tell Emmy that she’d met Hopi astronauts, who were hallucinations, and that she had burned rejection letters, which were real. Kayla left Jared, then she started dating married men. Emmy and Kayla had been friends for fourteen years when Kayla started saying she was lonely and her life was empty so she’d been researching suicide methods online. She said taping a plastic bag over her head after ingesting sleeping pills—and Dramamine, to keep from heaving—sounded the surest, cleanest and best.

She said this once. She said it many times. She said it to her therapists, to Emmy and the latest married man.

“No,” Emmy begged. “Surely you understand there is no coming back.”

“Yes,” Kayla said. “Of course.”

The officer who found her said she looked serene. She had not used a bag, just pills. She had already sent Emmy this bracelet as a Christmas gift:

These are only a few of Emmy’s suicidal friends and relatives. Emmy is wracked with guilt over the ones she could not save. She wishes everyone could hear her say: Please don’t. Because forever is forever. Picture whatever you love. Now picture never seeing, doing and/or having it again. Reach out. Get help. Actual help.

Emmy still talks to Kayla sometimes. Not out loud of course. Basically: Hi.

This essay had been written and its art mostly already drawn when a relative of mine committed suicide. We did not know each other well, but goodbye, RB.

Relephant:

A Personal Letter to Those Considering Suicide.

Author: Anneli Rufus

Editor: Catherine Monkman

Photo: Author’s Own

Read 3 comments and reply