My dad is by the front door, where his Air Force dog tag hangs, on a brass key hanger from the hardware store, with all the other keys.

He used to carry it on his key ring—I remember the jingles it all made when he was on his way to work in the mornings at 8:30a.m. and when he came home in the evenings at 5:30p.m.

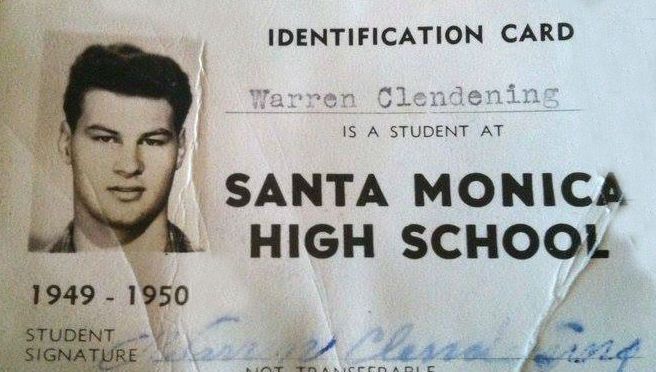

CLENDENING, WARREN

A03060620

T 58 A POS

PRESBYTERIAN

The tag was on my key ring for years, until I finally—and wisely—took it off. It would be just like me to lose it.

He’s over by the desk, where “his chair” is, the chair I sit in sometimes when I write. My dog chewed up the edge of that chair not long ago when he was mad I went to a Fourth of July picnic without him.

He’s in his college yearbooks, which I keep—he called them “annuals.” They barely survived the maddening, yearly flooding of the basement in our house growing up. The dog got to them too.

He’s in a copy of an article I have, that he wrote for his high school newsletter. It was published in the Santa Monica Evening Outlook, the newspaper he read every night in “his chair,” while he smoked his pipe and nursed a Manhattan in a can, that sat on a brown coaster. It came out a week after he died—his unintentional last words—a remembrance on his life at 15 in 1947. In it, he wrote:

“Is it possible we spent those halcyon days in a unique and special city, now so dramatically changed and altered, where everyone seemed to know everyone else and we seemed so interdependent, as in some mythical Brigadoon living only in our memories, where tradition and authority and trust and family and virtue and caring for one another were respected and honored? In our march into the future and with improvements in the qualities of our lives, have we lost and left behind a precious part of ourselves and bartered our birthright to a sense of community, commitment and civility for a quick lunch disguised as progress?”

I was 30 years old when my father passed away.

He was an attorney, and the kind of man who carried himself with a certain kindness and respectability—a very Capraesque quality that has decidedly passed on with the men of his generation. He had a heart attack while walking up the Santa Monica Courthouse steps on the way to trial on a Friday morning, within walking distance of the hospital where he was born. We were both born there, in the same exact room.

His first real job was washing dishes in the basement of that same hospital, after school and on weekends, for 72 cents an hour. He was a ripsaw operator in a lumber mill, member of two labor unions, beach bum, door-to-door salesman, Good Humor ice-cream man, elevator operator, truck driver, shop-worker at Douglas Aircraft, movie extra, law clerk, college instructor and corporation president. On the way, he lost a kidney to cancer, spent 21 years in active and reserve Air Force service, 38 years with my mother and 40 years in private law practice. He couldn’t type, couldn’t sing and he walked around on a cane.

He was idealistic. He was handsome and giggly. He was a wordsmith and a teller of sentimental stories from his childhood on the pier. He was a gentleman. He was Santa.

I have his watches and his high school ID’s. I had his gold Datsun 280ZX with the t-tops, the car I learned to drive on, until I (regrettably) ran it into the ground after five years.

Two-and-a half-years ago, on New Year’s Day, I gave his 1953 Omega watch to my husband as a wedding gift. My dad would’ve loved that. It had been given to him by his dad, my grandfather—a man I don’t remember.

He definitely would not love the fact that I crashed his car.

My dad is in the well-worn books on my bookshelf I love to look through, with titles like Familiar Quotations by John Bartlett and The Complete Works of Shakespeare. Because of all those old words on all those old pages, I became a writer, like my dad and my brother.

Dried, pink “While You Were Out” notes from his office, stuck to certain pages, reminded him of important pages from works like Don Quixote and Romeo and Juliet. Page 1,105 in one book is marked—it contains notable epitaphs.

“It is so soon that I am done for,

I wonder what I was begun for.”

~For a child aged three weeks, Cheltenham Churchyard

Apparently, Jack Cathc (paper ripped) called on July 27th—phone number 500-041 (paper ripped).

I wonder if he ever called that guy back? Or maybe he’d left the office early that day, to take the scenic drive home…

Relephant Read:

Happy Father’s Day! I love you, You Motherf**ker.

Author: Anne Clendening

Editor: Yoli Ramazzina

Image: Author’s own.

Read 3 comments and reply